Is a legendary coach’s successor doomed to fail? Let’s break it down

There's a chance Kalen DeBoer will stumble at Alabama. But it won't be because nobody has ever managed to succeed in this spot before

Last week, in the days after Nick Saban’s sudden retirement as Alabama’s coach – and the Crimson Tide’s whirlwind courtship of Kalen DeBoer – I used the opportunity to go over the general misery that plagued the men tasked with chasing a (quite literal) ghost in Tuscaloosa.

While the Alabama football head-coaching job is its own unique beast for reasons beyond the possibility of a brick getting thrown through your office window, the general idea of taking over for a legendary coach is something that dozens of programs in several different sports at the Division I level have experienced.

Even if the stakes and pressure aren’t always as high as they will be for DeBoer in the years to come, it’s still a daunting undertaking. Someone has built a program up to the point where it transcends the field or court of play. It becomes a cultural and civic institution, a common source of pride in which fans not only find passion, but some sense of identity and self-worth.

So while what awaits DeBoer was framed through a largely Alabama-centric lens, the experiment in which he’s about to take part has been conducted plenty of times in the three major sports of football, men’s basketball and women’s basketball. Just because Ray Perkins, Bill Curry, Mike DuBose, Dennis Franchione, Mike Price and Mike Shula failed to live up to the lofty expectations that greeted them doesn’t mean that DeBoer’s doomed for the same fate. Looking back at this, it’s also maybe best for the Crimson Tide to steer clear of coaches named ‘Mike.’

However, examining how other coaches in similar predicaments have done can be a potentially insightful exercise. If nothing else, it at least offers up a larger sample size and provides a clearer picture of some of the different ways this all can unfold.

If last week’s newsletter on Saban and the aftermath of his two-decade stay in Tuscaloosa seemed a bit bleak, consider this an injection of some much-needed optimism. These arrangements occasionally work out – and in some of these instances, you don’t even have to wait a quarter-century for a worthy heir as the Crimson Tide had to with Saban.

There’s a misnomer among some that replacing one of the sport’s luminaries is a fruitless endeavor. There’s some truth to it, sure. But while it may be a burdensome way to make a living, and while there are more failures than successes, there are some high achievers in the group, people who managed to excel in positions where so many others flop.

Before we dive into the numbers and what they mean, I wanted to touch on the methodology for this briefly.

First off, I limited it to post-World War II. Is it an arbitrary cut-off? Sure, but whatever lessons can be gleaned from these examples lose a little relevance if we delve too far into the past. Plus, defeating fascism is always a good way to kick things off.

To be considered a “legendary” coach, you need to fit two criteria. You need to have won at least two national championships – because for as much as luck is required to capture a championship, I have a hard time slapping the legend label on someone when they have as many titles as Gene Chizik – and you need to have been at the school in question for at least 10 seasons, which eliminates the Urban Meyers of the world whose fast rises and quick falls make it hard to determine whether they laid down much of a foundation at all to be handed off to someone else.

With that out of the way, here’s how the “man after the man” (and, in a couple of instances, the “woman after the woman”) fared:

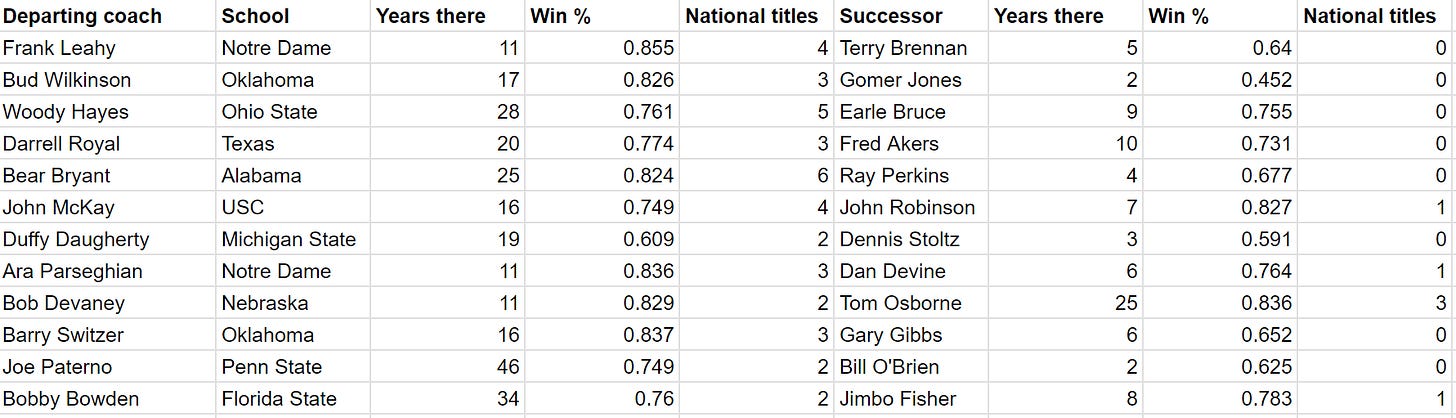

FBS football

In summation:

Four of the 12 successors won national championships

Three of the 12 went on to post a higher win percentage than their predecessor

Two of the 12 lasted as least 10 years

Four of the 12 were gone within four years

Five of the 12 won at least three-quarters of their games

Seven of the 12 won at least two-thirds of their games

One of the 12 finished with a losing record

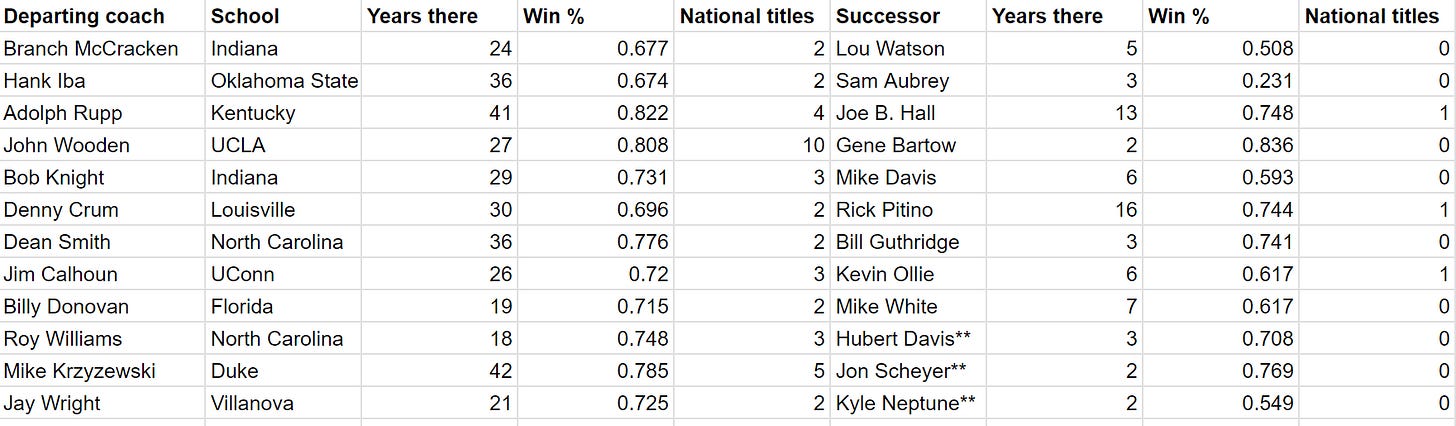

Division I men’s basketball

In summation:

Three of the 12 successors won national championships

Two of the 12 have a higher win percentage than their predecessor

Two of the 12 lasted at least 10 years

Three of the 12 were gone within four years

Two of the 12 have won at least three-quarters of their games

Six of the 12 have won at least two-thirds of their games

One of the 12 had a losing record

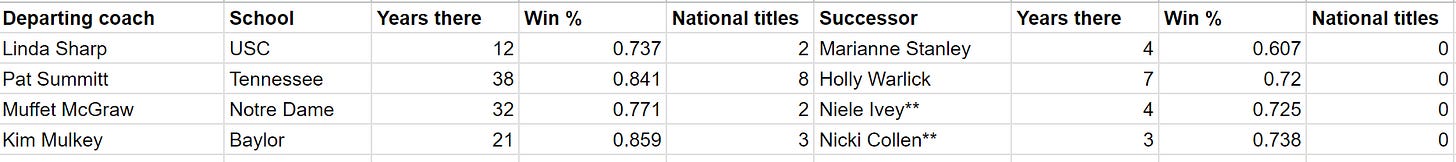

Division I women’s basketball

In summation:

None of the four successors have won a national championship

None of the four have a higher win percentage than their predecessor

None of the four have lasted at least 10 years

One of the four was gone within four years

None of the four have won at least three-quarters of their games

Three of the four have won at least two-thirds of their games

None of the four have a losing record

So what does all of this mean?

Are there any larger answers to be gleaned from all of this, mixed as the data is? Perhaps.

One is that not all legends are created equally, meaning that some of their successors had no realistic chance of reaching the same heights. Bob Knight’s quick and controversial exit put Mike Davis, three days before his 40th birthday and with no previous head-coaching experience, in a hard-to-win position, though he managed to do well enough initially, making it to the national championship game in his second season.

Similarly, Bill O’Brien was never going to come close to what Joe Paterno accomplished for, well, obvious reasons. His 15-9 record in two seasons underscores just how well he did in one of the more undesirable situations in modern college football history.

As O’Brien showed, a simple win-loss record doesn’t always tell the full story, either. Gene Bartow, who followed John Wooden at UCLA, actually had a higher win percentage than the Wizard of Westwood, but the pressure of the job and everything that came with it wore on Bartow, enough to get him to leave after one year to be a basketball coach and athletic director at UAB — which didn’t even have an athletic department at the time he was fleeing from southern California.

As the Los Angeles Times noted at the time:

Although Bartow had a 52-9 record at UCLA and won two Pacific 8 championships, he was continually second-guessed by the alumni for not being as successful as Wooden.

The criticism — along with letters in the newspaper and some sharp comments from a radio sportscaster — bother Bartow, who is admittedly thin-skinned.

He recently stormed off of a radio talk show saying '“Hogwash, hogwash” when a caller criticized him. He later said he (Bartow) was too controversial.

UAB apparently offers the low-key job he wants.

Some of the moves were relatively obvious to make, like Rick Pitino taking over for Denny Crum at Louisville. It takes a tactful athletic director to orchestrate such a succession plan, but it doesn’t take any special insight into how that person might do once in the job. That separates it a bit from what Alabama just experienced in a search where there were plenty of quality candidates, but no guarantees.

Most any school in this situation is faced with the decision of whether to promote from within and try to maintain the framework, culture and, (fingers crossed) all the wins of the departing folk hero or venturing outside that tent to see if it can land who they feel is the best, most deserving candidate.

Is there one of those approaches that works better than the other?

If you’re looking purely at national championship winners, there’s a 4-3 advantage for coaches who were promoted. But when you take a peek at the more decidedly disastrous tenures, like the two sub-.500 successors, both were promoted. Of the seven coaches who have won at least 75% of their games, four were external hires. Of the 15 coaches who have won at least two-thirds of their games, eight were external hires.

All of this is to say it’s really anyone’s guess, especially with three of the successors in men’s basketball so early in their careers. So far, Hubert Davis at North Carolina and Jon Scheyer at Duke look like capable stewards of what they inherited while Kyle Neptune at Villanova looks to be fumbling the bag and potentially setting himself up for an extremely uncomfortable offseason.

So, to any Alabama fan who might be reading this, rejoice. The gloomy scenario laid out last week isn’t one that your beloved program will necessarily have to suffer through. If anything, the fate of your post-Saban existence is something closer to a coin toss. And what’s the most someone has ever lost on a coin toss?

(Photos: USA Today Sports, Associated Press)

When I read this, I was thinking about a lot of these basketball programs - Duke, NC and Villanova. They are well established and so are the expectations of the fan base, with social media to let loose with all their demands. Now with the portal, there's even a great sense of "you can fix it now - just go find someone!"

I'll be very curious to see what happens at UConn when the inevitable day comes that Geno Auriemma retires.

That top photo looks like it's in the Roll Tide Church of Tuscaloosa and that they preacher's delivering a eulogy at a funeral.