Are we about to see how ugly things can get at Alabama?

Nick Saban oversaw a period of unprecedented success at Alabama. But after his retirement, can the relative calm those wins created remain?

This past week, Nick Saban upended much of the college football world when it was announced that the legendary 72-year-old Alabama coach was retiring.

For the better part of the past two decades, Saban has been a singular force in the sport, someone who changed the way rosters were built, defenses were played and the way that football programs as a whole were envisioned. He is, by almost any measurement available, the most decorated coach in the history of college football.

With six national championships and nine SEC titles, Saban not only revived one of the most storied programs in the sport, but elevated it to heights it hadn’t previously enjoyed – which is saying something at a school where Bear Bryant coached.

Consider what unfolded over his 17 years at the helm in Tuscaloosa:

During Saban’s tenure, Alabama had more first-round NFL Draft picks (44) than losses (29).

After going 7-6 in his debut season in 2007, Saban’s teams had 16 straight seasons in which they finished the season ranked in the top 10 nationally. In 12 of those seasons, they were in the top five.

Over those final 16 seasons, he went 199-23, including a 116-14 mark in the SEC, which was universally considered the toughest and deepest conference in the sport during the entirety of that stretch.

Prior to this most recent season, every Alabama player who played under Saban and stayed in the program all four years won at least one national championship.

Beginning in 2008, he never had a recruiting class ranked outside of the top five nationally. Of those 17 classes, 15 were in the top three and eight were ranked No. 1.

Since Saban was hired by Alabama in January 2007, 54 other coaches have been in charge of SEC programs.

Yet despite all of those resounding, jaw-dropping feats, his greatest achievement was perhaps his most overlooked one. For nearly 20 years, he made Alabama and everything that surrounds its football program seem normal.

As the Crimson Tide embark on a new, decidedly murky chapter without that steady and unfathomably capable hand leading the way, it’s not clear whether that will remain the case.

Will Alabama be the next fallen dynasty?

Dynasties are constructed to eventually crumble. Over time, something that was once unconquerable becomes much less daunting.

Of all the bullet points on Saban’s lengthy resume, one of the more impressive might be that Alabama never really fell off under his watch. Even his 2007 team that now exists as a punchline saw each of its six losses come by seven points or fewer, including a seven-point setback against eventual national champion LSU. What turned out to be his final Tide team, which looked shockingly mortal to start the season with a loss to Texas and a lethargic win over South Florida, managed to win the SEC, make the College Football Playoff and come a fourth-quarter Michigan comeback away from playing for yet another national title.

Without him, it remains an open question of what might become of Alabama.

If the history of major college sports is any indication, there’s reason to be concerned. Even if a luminary of a coach leaves behind a winning program on stable footing, there’s no guarantee it will ever be what it once was. In fact, it almost never is, at least in the years that immediately follow the transition.

Take UCLA men’s basketball, for instance. The Bruins are a machine without peer in NCAA football and men’s basketball, with John Wooden stepping away in 1975 after winning his 10th national championship in a 12-year stretch. In the 19 years following Wooden’s retirement, though, the Bruins made just two Final Fours and it wouldn’t be until the 20th year that they would snag their 11th title. They haven’t won one since or come particularly close.

The examples extend into football. Since Tom Osbore’s retirement following the 1997 season, Nebraska has made what are now considered New Year’s Six bowls just three times and have lost fewer than two games in a season only once. USC has lost fewer than three games in a full season only once since Pete Carroll left after the 2009 season. In that stretch, a program that won two national championships and finished in the top five seven times under Carroll from 2002-08 has only one top-five finish and two top-10 finishes.

In the case of both programs, there were inherent advantages that seemingly should have continued into perpetuity. Nebraska was the primary athletic obsession in a football-mad state that would do whatever it could to keep its beloved Huskers relevant while USC was the glamor program with unlimited cultural cachet that happened to be located in the middle of one of the most fertile recruiting areas in the country. Yet, somehow, both fell off and haven’t truly recovered to what they once were.

If this sounds familiar for Alabama, it’s because it should.

After Bryant stepped away after the 1982 season, a program that won three national championships in his final 10 years at the helm struggled (relatively speaking), going 58-25-1 in the seven seasons after Bryant’s exit. Bryant protege Gene Stallings restored at least some of the luster that had been lost in the years following his mentor’s retirement – winning a national championship in 1992, the Tide’s first since 1979 – but after he departed following the 1996 season, Alabama was once again left in the proverbial wilderness, going 67-55 in the 10 years between Stallings and Saban’s stints.

It’s part of the Saban mythology – he not only won as much as he did, but he did so at a place that seemed so fundamentally broken at the time of his arrival, prompting many to wonder whether it could ever become the mighty force it once was.

Those doubts existed for good reason. In some of those years between Bryant and Stallings and then Stallings and Saban, the win-loss record only does so much to highlight just how turbulent and dysfunctional things were at college football’s marquee program.

There’s some danger to being the Alabama coach. Just ask Bill Curry’s window

In the same way that the American south is often incorrectly thought of as a monolith, the same principle applies to the various schools and their football programs within the SEC.

Outside of Vanderbilt, every program in the conference has a passionate and vocal fan base that lives with the successes and failures of its favorite team in ways that are both endearing and a little alarming. As the league itself says, it just means more.

There are levels to that obsession, though, and entrenched firmly atop that pyramid of football zeal is Alabama.

It’s one of just two states in the SEC with multiple conference members and unlike Mississippi, both of its schools have been historically competitive and each captured at least two national championships. The rivalry between Alabama and Auburn is fierce, an ever-burning hatred that occupies the minds of the fan bases 12 months a year and fuels a perpetual arms race in which, admittedly, one of the programs has been much more accomplished than the other.

That drive creates success and that success creates a hunger for more success that is only satiated by the most coveted and difficult-to-obtain rewards the sport has to offer.

It has a profound effect on those who follow the programs most fervently, which, in a place like Alabama, ropes in much of the state.

Think of the most unhinged calls you’ve ever heard on the Paul Finebaum Show. There’s a decent chance the person on the other end of the line was an Alabama fan, was talking about Alabama or was calling from within the state’s borders. The late Harvey Updyke, who poisoned two of the famous oak trees at Auburn’s Toomer’s Corner, was an Alabama diehard who lashed out after Auburn beat the Tide in 2010 and some of its fans celebrated by taping a Cam Newton jersey on Bryant’s statue outside the stadium. Phyllis, the caller whose feisty and fiery contributions over the airwaves turned her into one of the show’s main characters, was an Alabama fan from Mulga, about 12 miles west of Birmingham. Just this week, a caller, Legend from Alabama, threatened to douse himself with gasoline and set himself on fire at the 50-yard line of Alabama’s Bryant-Denny Stadium if the Tide hired Dabo Swinney to replace Saban (mind you, Swinney is an Alabama native and former Tide player who has won two national championships at Clemson).

That unrelenting passion can push a program to greatness. The coaches and players within a program work so tirelessly to avoid failure because they know how miserable it is to endure. But should that failure arrive, life can become unbearable.

That unwavering and palpable intensity is much like a metaphor Mike Krzyzewski used in an ESPN documentary to describe Christian Laettner. In this instance, Alabama fans are like fire. If managed effectively, it can heat up every apartment in a building. If it can’t be controlled, though, it will burn the entire structure down.

Just ask any Alabama coach of the past 50 years who wasn’t Bryant or Saban.

Bryant’s immediate successor, Ray Perkins, struggled initially, but eventually settled into the role, going 19-5-1 in his third and fourth seasons. Still he faced mounting pressure, the kind Bryant hoped to shield him from in his post-coaching role as Alabama’s athletic director, only to die only a few weeks later at the age of 69.

Facing growing discontent among fans and boosters, Perkins left after his fourth season – not for a more prestigious or vaguely lateral position, but to be the head coach of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, who had gone 48-116-1 in their decade of existence and were the laughingstock of the NFL.

That was comparatively mild to what his successor, Bill Curry, encountered during his time in Tuscaloosa.

Curry wasn’t a popular hire, having gone an underwhelming 31-43-4 at Georgia Tech and having played at Georgia Tech in the early 1960s, when it was a bitter SEC rival of the Tide’s. Like Perkins he struggled at the outset, going 7-5 in his first year, but went 9-3 in his second and 10-2 in his third.

He never garnered much affection, though.

Alabama won double-digit games just once under Curry and, more unforgivably, he went 0-3 against archrival Auburn. He claimed to have received death threats and, most infamously, had a brick thrown through his office window in 1988 after a 22-12 loss to Ole Miss, Alabama’s first defeat ever in Tuscaloosa against the lowly Rebels. A segment of the Tide fan base believed it to be an orchestrated incident, with Curry or someone close to him doing it, but both Curry and Eddie Franks, the building manager at the time, said it happened.

“Why would anybody make up a thing like that?” Curry said years later. "I just walked in my office, and there were glass shards around and there was a brick lying there. I thought, well, isn't that clever? ... I mean, somebody missed their cool and threw a brick.”

After going 10-2 and making the Sugar Bowl in 1989, helping him win SEC coach of the year and earning Alabama a share of its first SEC championship since 1981, Curry was handed what he believed to be an insufficient new contract, which included no raise and the removal of his power to hire and fire assistants.

Upset by the offer and worn down by what former assistant Tommy Bowden described as "tension for three straight years,” Curry left Alabama to become the new head coach at Kentucky, an SEC afterthought that had made only three bowls in the previous 37 years.

“People say Coach Bryant would have rolled over in his grave because Alabama hired Bill Curry,” said Don Lindsey, former Alabama defensive coordinator, to the Associated Press. “I say he would have rolled over in his grave because of the way Bill has been treated.”

Stallings offered a seven-year reprieve, but after he left, the drama continued for another decade.

Mike DuBose, Stallings’ successor, took the Tide to an Orange Bowl in 1999, but he was fired a year later in the middle of a woeful 3-8 campaign. To emphasize DuBose’s misery during this stretch, he offered his resignation after the third game of that season, thus foregoing whatever buyout would be owed to him, but athletic director Mal Moore refused it.

Dennis Franchione left after two years and became the third post-Bryant Alabama coach to bounce immediately after a 10-win season for a lesser job (in his case, Texas A&M, as the Tide were dealing with the effects of NCAA sanctions). Mike Price lasted just five months, though in fairness, that was more of a Price problem than an Alabama one. Mike Shula, a former Alabama player and assistant, was fired in 2006 after four largely unsuccessful years, opening the way for Saban.

There’s reason to believe the Tide are not too big to fail

So what will become of this latest chapter in Alabama’s long, storied and undeniably unusual coaching history?

There’s a train of thought that the program is too big to fail, that Saban built it into the kind of financial and institutional behemoth that not even a few disappointing seasons can topple. In 2022, for example, the university spent $78 million on football, beating out the next-closest SEC school by $17 million.

The Alabama he’s leaving is also drastically different than the one he arrived at in 2007, due at least in some part to what his teams managed to do on the field. A university that in the early 2000s had a 3-to-1 ratio of in-state to out-of-state students now has an undergraduate population in which 58% of its students are from outside Alabama, each of whom shells out more than $30,000 in tuition to attend. It’s part of a concerted strategy from the school’s admissions office, but it’s also proof that sometimes, the oft-touted front porch role an athletic department plays isn’t always empty rhetoric.

Such a stance, though, ignores some important information. Alabama’s lulls after Bryant and Stallings means it’s liable for such droughts again. It’s not the same kind of turnkey operation that Ohio State is, a program where a permanent head coach hasn’t finished a tenure having won fewer than 70% of his games.

For all of its resources and lofty stature, the Tide aren’t necessarily well-positioned for the NIL deals that now shape college athletics at its highest levels. On the heels of Saban’s retirement, multiple outlets have reported there was a “Saban discount” for players coming to Alabama, meaning they were willing to take less money than they were offered elsewhere for the privilege of playing for Saban and, based on his track record, increasing their chances of making the NFL. Without him, the university and its backers will have to pony up because while it may feel sacreligious to say Alabama is now just like some of its peers, it kind of is.

That optimism also looks past one of the things that made Saban such a quintessentially triumphant figure – his ability to control his surroundings, be it his players, coaches or anyone trying to exert their influence in his general realm. He took a first and all-important step shortly after he was hired, as journalist Steven Godfrey, writing for the Washington Post, detailed in a piece Friday:

Saban’s first and greatest victory in Tuscaloosa occurred when he brought its famously meddlesome, fractious booster corps to heel. This sounds like a logical first step when taking over a Tiffany brand such as Alabama, but it proved impossible to accomplish for the coaches who preceded him.

The gist of the famous meeting, as the story goes, was that Saban assembled every check-writing, cash-funneling, self-anointed important person in the orbit of Alabama football and broke their sense of self-importance with totality. From then on, Alabama would function, full stop. No one group of boosters, no region of the state or greater Southeastern area, was more or less important by its own estimation. Saban was, from then on until he was no longer the coach, the tip of the spear.

By doing so, Saban eliminated much of the dysfunction that had doomed so many of his predecessors and made his dominant march through college football possible.

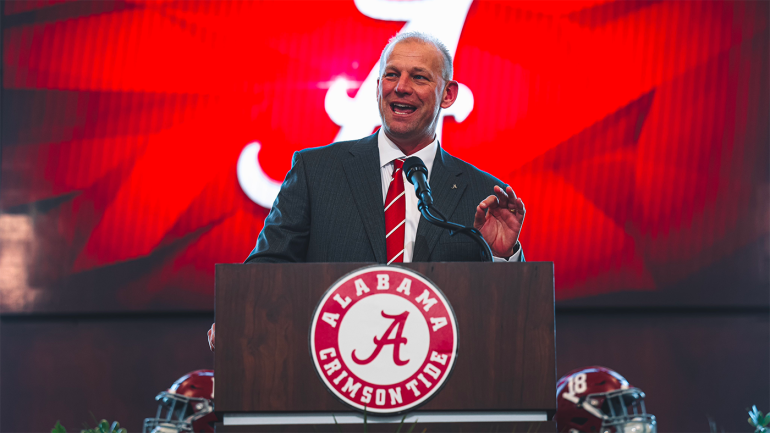

Though a cynical reading of history suggests otherwise, it’s possible Saban’s successor, Kalen DeBoer, thrives. After all, he is 104-12 over his head-coaching career and just went 25-3 at Washington, which was 4-8 the season before he took over.

In a number of profiles that came about about DeBoer around the national championship game – which his Huskies lost 34-13 to Michigan – and in the days leading up to his hiring at Alabama, his calm and unflappable nature was often cited.

“As head coaches, we all talk about poise in the moment, but he just lives it,” Washington State coach Jake Dickert told The Athletic last week. “He is so cool, so collected.”

To survive what awaits him, he better be.

(Photos: USA Today Sports, Alabama Athletics)

it's never easy to follow a legend. It can be like stepping off a ledge into an abyss. Plus, people are crazy, absolutely insane - like the examples you provided. The guy who poisoned the trees at Auburn named his daughter Ally Bama. It's funny you mentioned Vandy in this piece because I've been wondering if the SEC would ever tell them to go elsewhere.