The WAC has been conference realignment’s most dogged survivor. Can it stay that way?

Over the past three months, four of its members have announced they're leaving, thrusting the league once again into uncertainty

There’s an unassuming, six-story office building located right off I-25 in Greenwood Village, Colo., a southern suburb of Denver, that stands today as something of a ghost.

It’s a red-brick structure with tinted windows, the kind of place that you’d see at any office park erected over the past 40 years. On a large black sign outside the building, there’s a list of tenants that has clearly dwindled over the years. One of them in particular stands out – the Western Athletic Conference, in suite #300.

The Division I conference commonly known as the WAC hasn’t occupied the office space since 2022, when it relocated to Arlington, Texas, but something about the arrangement stays with me and brings a small smile to my face every time I pass it. Pouring significant financial resources into conference headquarters isn’t a wise move – look at how well those swanky downtown San Francisco digs worked out for the Pac-12 – but the WAC’s since-abandoned space in Colorado feels kind of illustrative of the conference’s existence: still there in name, but always in a period of transition.

This year, that’s been more evident than ever.

Over the past three months, a league that had 11 schools playing men’s basketball has seen more than one-third of its membership announce they’ll be heading elsewhere. In March, Texas-Rio Grande Valley informed the WAC it would be leaving for the Southland Conference beginning next season. In May, it was formally announced that Grand Canyon and Seattle would be heading to the West Coast Conference, effective July 2025. A few weeks later, Stephen F. Austin revealed that it would be bolting, as well, and, like UTRGV, would be departing for the Southland immediately.

This turbulence isn’t anything new for the WAC. Over the past quarter-century every Division I league has been touched in some way by conference realignment, but for the WAC, it’s been a period of even more chaos.

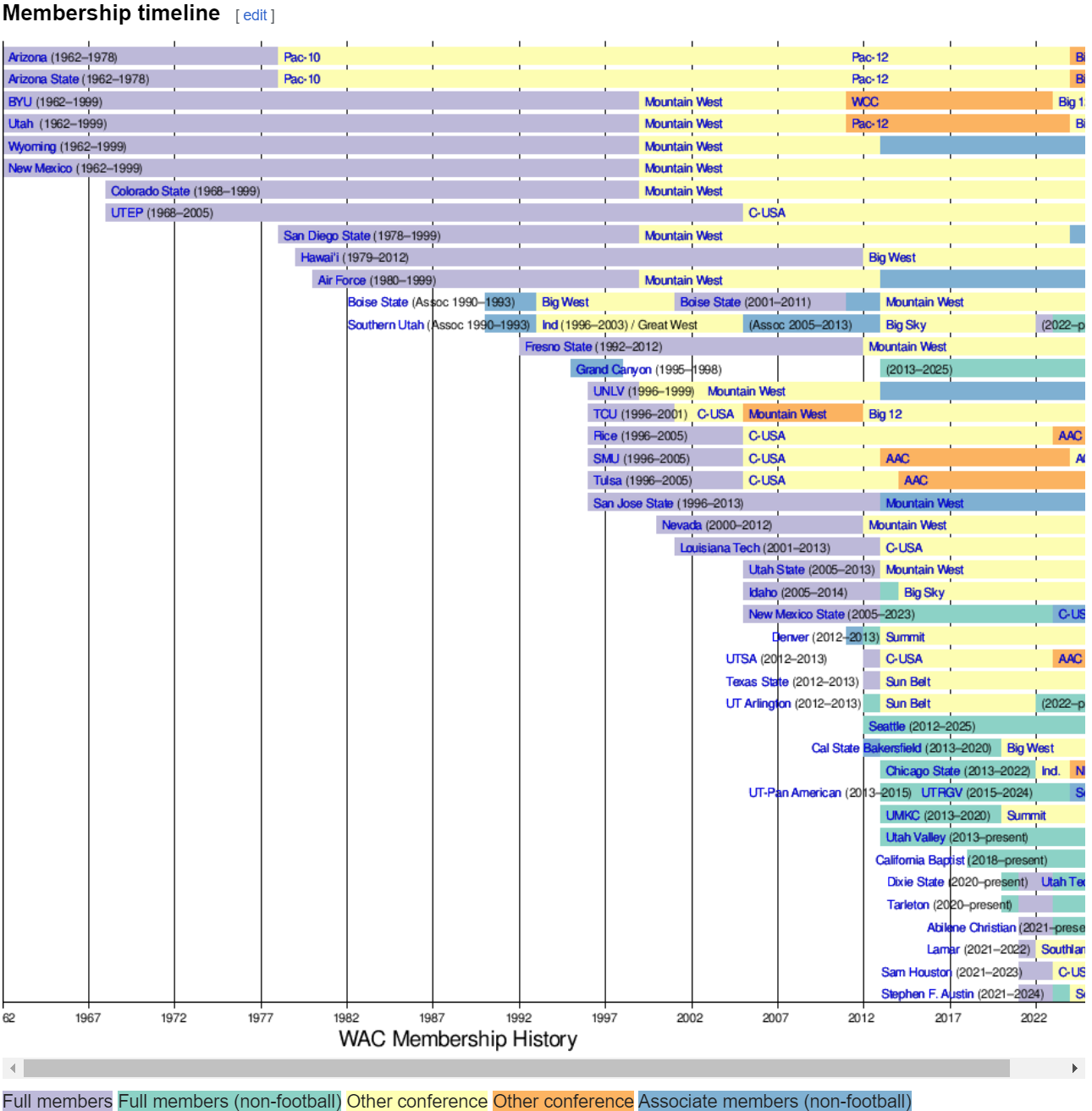

Going all the way back to its founding in 1962, the WAC has had 32 former full members, 30 of which have left since 1999 (not including the most recent, soon-to-be departures). Exactly half of those 32 losses have come since 2013. Since 2020, they’ve lost six, a number that will officially increase to at least 10 in the next 13 months.

That instability has made the league something of a chameleon, a shape-shifter not by choice, but out of necessity. The six teams that were a part of the WAC at its inception more than 60 years ago are long gone. Not even a single team that was in the WAC in 2011 is still around, as its longest-tenured current full member didn’t come aboard until 2012 – and that school, Seattle, won’t be around in a year.

All of that shuffling comes with a slew of questions, some of which are more uncomfortable than others. How did the WAC get to this point? And as its ranks continue to get decimated, is there still a place for it in the modern college athletics landscape?

The wacky history of the WAC

Beginning in the late 1950s, BYU athletic director Eddie Kimball initiated conversations with other university administrators whose teams competed in various other western-based leagues – the Border, Skyline and Pacific Coast Conferences – about coming together to form a new conference that would better meet their needs.

From those talks, the WAC was born.

Starting with its original sextet of Arizona, Arizona State, BYU, Utah, Wyoming and New Mexico, the league quickly expanded – at least by the standards of the time – bringing in Colorado State and UTEP six years later.

That first lineup is indicative of something that’s been true for much of the WAC’s history. While it’s arguably not good for the conference’s overall health and longevity, it’s been a springboard for schools to wind up in bigger, more prestigious leagues. Six schools that are part of a Power Five conference or will be in the next few weeks – Utah, TCU, Arizona, Arizona State, SMU and BYU – once called the WAC home.

In the years and decades that followed its formation, the WAC built a proud and notable history.

It produced a national champion in football when BYU claimed one of the more improbable titles in 1984. The two Arizona schools combined to win five College World Series championships from 1965-77. It had two more CWS champions in the aughts, with Rice winning in 2003 and Fresno State in 2008. In 1998, Utah men’s basketball made the national title game, where it coughed up a 10-point halftime lead in a loss to Kentucky. Two months after that, Fresno State won the Women’s College World Series.

That success continued into the new millennium, most noticeably in football. That Boise State team that famously toppled Oklahoma with a series of trick plays in the 2007 Fiesta Bowl? It was a WAC team. So was Hawaii, which made the Sugar Bowl the following year (where it didn’t fare quite as well as Boise State). In 2009, when Boise State went 14-0, won the Fiesta Bowl yet again and finished No. 4 in the country, it was still in the WAC.

“That original WAC with BYU and Utah and stuff, they had games on ESPN,” Kyle McDonald, the publisher of the excellent WAC Hoops Nation Newsletter, told me. “They were on Big Monday, Super Tuesday. Those big-time, late-night games, it was like Pac-12 After Dark for a time. That went away.”

Even as some of its teams were flourishing, the WAC was beginning to endure some of the instability that has come to define it.

The Arizona schools, the flagship institutions in a rapidly growing state, left in 1978 to join what became the Pac-10. When the Southwest Conference dissolved in 1996, the WAC was proactive, adding Southwest Conference castoffs SMU, TCU and Rice, as well as Tulsa from the Missouri Valley Conference and UNLV and San Jose State from the Big West. With that expansion, the WAC became the largest league in college athletics, with 16 teams long before anyone else adopted the superconference model.

Its sheer size, however, made it unwieldy, even with the league divided up until four four-team quadrants. There wasn’t strength in those numbers, but rather discontent, with several schools looking around and realizing the conference they joined didn’t resemble the one they currently inhabited. Operating costs had risen significantly, travel times were bloated and a proposed realignment within the league would have separated in-state foes like Colorado State and Air Force.

In 1998, the presidents of Air Force, BYU, Colorado State, Utah, and Wyoming met at Denver International Airport and, after some discussion, opted to break away from the WAC, inviting San Diego State, UNLV and New Mexico to join them in what became the Mountain West Conference.

“'We've spent most of our time in conversation trying to respond to the question, 'Is there a way to make this 16-team conference work?'” Colorado State president Al Yates, who was also chairman of the WAC board of directors, said to USA Today. “Our conclusion in all that was that there was not.”

In the 26 years after that fateful meeting, the WAC has largely been on its heels, doing whatever it can to remain afloat.

For more than a decade, from 2001-12, the league stretched from Ruston, La. – home of Louisiana Tech – all the way out to Hawaii, a distance of more than 4,000 miles. As recently as two years ago, Chicago State, which isn’t even in the western half of the United States, was a member.

The membership timeline graphic on the WAC’s Wikipedia page is a sight to behold.

To replenish its ranks, it has turned to not only other low-major conferences for potential matches, but the lower levels of college athletics. Cal Baptist joined in 2018 after moving up from Division II. Tarleton State and the oddly named Dixie State (now Utah Tech) made the same jump in 2020. So did Grand Canyon in 2013, which came with the added distinction of being the first for-profit Division I institution.

In 2021, the league got aggressive and added five new schools – Southern Utah, Abilene Christian, Lamar, Stephen F. Austin and Sam Houston State.

“I think we hit a home run today,” WAC commissioner Jeff Hurd said at the time.

Those maneuvers, however, are part of what has become a vicious cycle for the WAC. Whenever the league is proactive and appears to gain some sense of security, it’s quickly raided and finds itself in the same position it was a year or two earlier.

Eight schools that have accepted invitations to the league since 2012 have since left, five of which didn’t stay for more than two years. That home run Hurd believed he whacked in 2021 didn’t come with the desired results. Three of those five additions won’t be in the conference for the 2024-25 athletic calendar.

Maybe no league has faced the kind of persistent and existential threats the WAC has over the past 15 or 20 years. Yet through the continuous turnover, it has managed to survive.

After this most recent wave of defections, can it do so once again?

What comes next for the WAC?

For all the uncertainty it faces at yet another fork in the proverbial road, the WAC at least has some assurances.

Even without Grand Canyon, Seattle, UTRGV and Stephen F. Austin, the league has seven members for non-football sports heading into 2024-25, putting it right above the NCAA-mandated minimum of six in order to be recognized as an official entity.

With that established, the WAC faces the same question it has stared down more times than it has likely cared for over the past decade – where does it go from here?

It’s possible the conference doesn’t panic or give into any potentially impulsive decisions and stands pat, believing it has a solid core of seven members rather than frantically seeking out schools that are either bad fits or short-term fixes. Should it opt for expansion, it can do what it has done with varying degrees of success over the past 15 years and rummage around the Division II and even NAIA ranks for additions that could make sense.

Not all of its losses are created equally, either, at least in men’s basketball. While Grand Canyon, a burgeoning power at that tier of the sport, has been the WAC’s NCAA Tournament representative in three of the past four years and Seattle is an improving program with three straight Division I seasons of 20-plus wins for the first time since Elgin Baylor played there in the late 1950s, Stephen F. Austin was never able to match the success it had in its final decade in the Southland and UTRGV finished in the bottom three of the conference standings each of the past three seasons.

This most recent crisis, however, is coming at an interesting and perhaps inopportune time in the WAC’s history.

The same league that produced those aforementioned Boise State and Hawaii teams that crashed the BCS stopped sponsoring football following the 2012 season, when a rash of exiting programs left it with just two football-playing members remaining.

In Jan. 2021, with the impending arrival of five new colleges, the WAC announced it was reinstating football and competing at the FCS level. With its relatively low numbers and ever-changing membership, the WAC partnered with the ASUN to form a separate football organ, the United Athletic Conference. In 2023, its first season of competition, the UAC had nine teams, with Austin Peay in Tennessee finishing atop the standings with an undefeated conference record.

The presence of football provides a potential thorny discussion point for any prospective new members the WAC seeks out. Does the WAC want football members to bolster the UAC? Does a university with serious football aspirations, even just at the FCS level, want to enthusiastically tie its future to a hodgepodge football conference that seems like more of a temporary fix than a viable long-term entity? Even if it’s comfortable with the nascent UAC, does it want its football program in a league separate from all of its other sports?

If there’s a league adept at navigating the murky waters of college sports, it’s the WAC. But whether that can continue to be the case remains an open question.

“I don’t know where they go,” McDonald said. “The ADs that I’ve talked to, they just don’t know. When people look at the Western Athletic Conference right now, are those schools able to say the WAC is a viable option? That’s the tough part – where do you go from here? You have teams that have football and you have teams that don’t have football. That’s the challenge. Are you going to add football and are you going to add teams with football? Or are you going to make it more of a basketball-centric conference? [WAC commissioner] Brian Thornton has a lot on his plate to figure out what they’re going to do and what direction they’re going to go because even the athletic directors around the league don’t know right now.”

(Photos: Getty Images, Associated Press)