The outrageous and irreplicable college career of Pistol Pete Maravich

The former LSU star's career scoring record is going to fall to Caitlin Clark, but that might be his only record anyone will ever come close to touching

Here’s the promised second installment of the series built around Caitlin Clark’s pursuit of various Division I career scoring records. Today, we shift over to the men’s game.

At some point in the next week, almost certainly by the end of her team’s March 3 regular-season finale against Ohio State, Caitlin Clark will have cleared another historical marker.

Having already eclipsed Kelsey Plum’s NCAA Division I women’s basketball career scoring record in a Feb. 15 win against Michigan, the Iowa superstar will, barring something drastic and unforeseen, become the all-time leading scorer in men’s or women’s Division I basketball.

After scoring a modest (by her exceptionally lofty standards) 24 points in a loss Thursday at Indiana, Clark sits at 3,593 career points, putting her just 74 behind a man who’s less a historical figure in the sport than an urban legend – Pete Maravich.

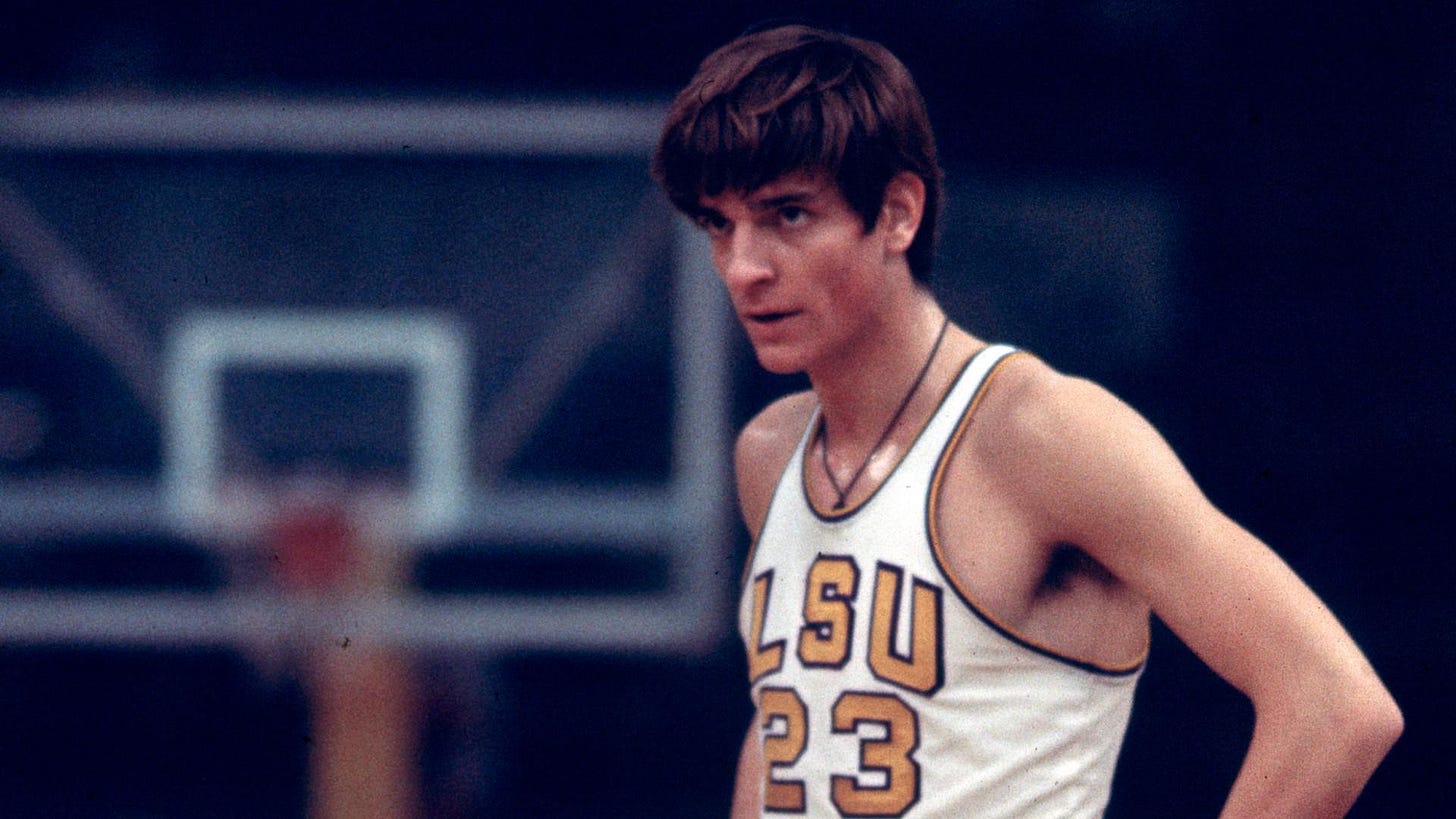

Maravich is still a storied name in the sport more than 35 years after his death in 1988. His nickname alone, “Pistol Pete,” resonates with fans of the game today, even for those who never watched him play or, like me, were even alive when he passed away. He was a five-time NBA all-star, an NBA scoring champion, a member of the league’s 75th anniversary team and a Naismith Memorial Hall of Fame inductee.

For all he accomplished at the professional level, and for as much as that adds to his larger mythos, it was college where he shined the brightest, putting together a three-year run at LSU with no statistical equivalents in college basketball history at any level.

Clark is going to surpass Maravich’s career scoring output. That much appears certain. But there are many other records he amassed in his time in Baton Rouge that will never be broken, let alone even vaguely approached.

It’s not any kind of knock against Clark, a prodigious talent who has attracted attention to her sport in a way that few, if any, over the course of its history ever have. The truth is, nobody is ever catching Pistol Pete.

How the legend of Pistol Pete was born

The legend and aura surrounding Maravich was already being scripted by the time he joined LSU’s freshman team for the 1966-67 season.

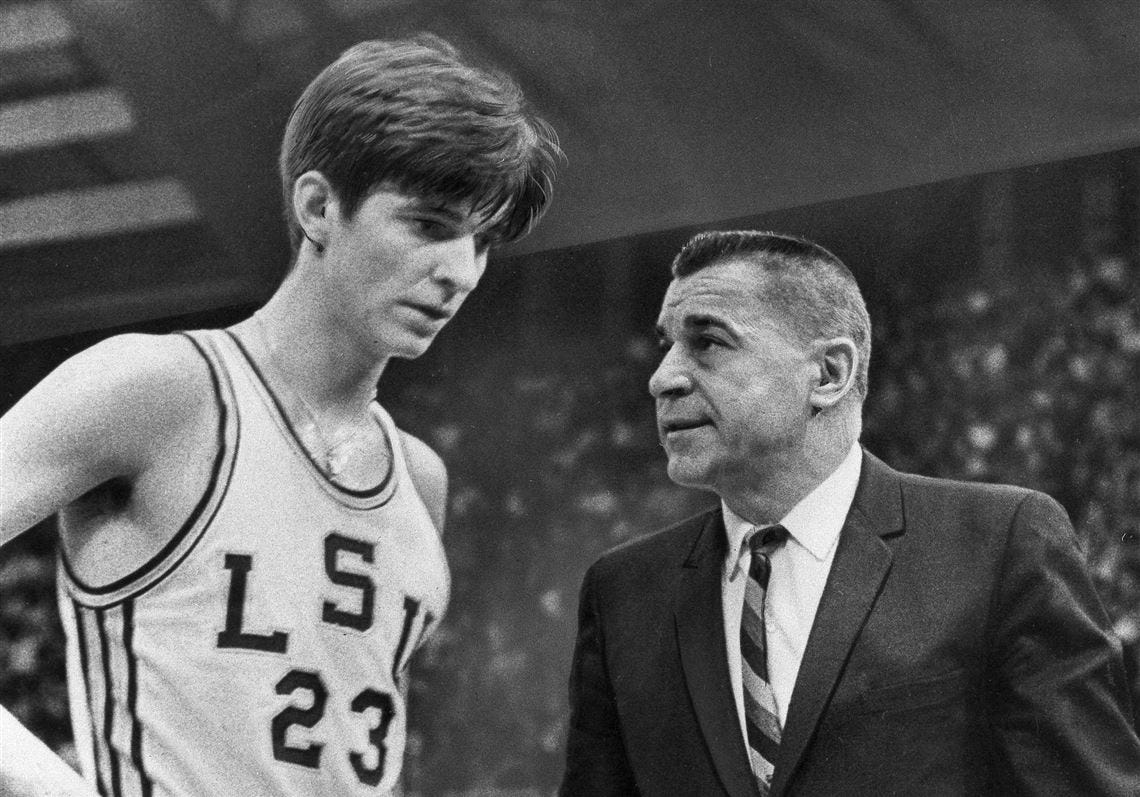

Much of the reason for that could be tied back to the same person who was the primary factor in Maravich ending up at LSU in the first place – his father, Press.

Born Peter Maravich in 1915, he earned the nickname Press by selling copies of the Pittsburgh Press newspaper in his hometown of Aliquippa, Pa., a small mill town outside Pittsburgh that has produced the notable athletic likes of Tony Dorsett, Mike Ditka, Darrelle Revis, Ty Law and, of course, Pistol Pete himself. Maravich played professional basketball for about a decade in the Basketball Association of America, a forerunner of the NBA. The end of his playing days in 1947 coincided with the start of his coaching career and the birth of his son.

The two events were inextricably linked. The elder Maravich would work tirelessly to bring the best out of the teams he coached while doing the same with his son.

Press was famously (or perhaps infamously) diligent in molding Pete into a basketball prodigy, running him through drills for hours a day. The most widely discussed of those involved Pete dribbling a ball beside the open door of the family car while Press drove. Press allegedly threatened to shoot Pete with a .45-caliber pistol if he drank or got into some kind of trouble. When, while the head coach at LSU, Press offered Pete a scholarship to play for the Tigers, he told him that if he didn’t sign, he should never come home again. Originally, Pete had expressed a desire to play at West Virginia, but after his father bought him a car, he agreed to go to LSU.

Press rose through the coaching ranks relatively smoothly, with perhaps no jump more sizable than going directly from Baldwin High School in suburban Pittsburgh to the head coach at Clemson. From there, he moved on to N.C. State before being hired by LSU in 1966.

He wasn’t the only Maravich to arrive in Baton Rouge that year. And after one season playing for the school’s freshman team, Pete, at long last, got the chance to play for the man who had the single biggest hand in shaping him as a player.

What ensued was something college basketball will never see again.

As a sophomore in 1967-68, Maravich averaged 43.8 points per game. It would be the lowest scoring tally of his college career. The next year, he averaged 44.2 points per game. By the time he was a senior, he averaged 44.5 points per game while earning national player of the year honors.

For all his wizardry on the court, Maravich didn’t reach those figures by being extraordinarily efficient or lethal. After all, he never made more than 44.7% of his shots in a season.

Rather, he shot the ball at a greater frequency than any player to ever grace a college court. Maravich never averaged fewer than 37.5 field goal attempts per game and maxed out at 39.3 shots per game as a senior. Over a 40-minute college game, that’s about a shot per minute. And mind you, this all occurred before there was a shot clock.

Over his three years at LSU, he was responsible for 3,166 of his team’s 6,284 shot attempts, or 50.4%. None of Maravich’s teammates ever averaged more than 13.2 shots per game over the course of a season. During his junior season in 1968-69, he attempted 37.5 shots per game while his next-closest teammate averaged 8.2.

At least offensively, it was a strategy that paid off. The Tigers ranked in the top 10 of about 200 Division I teams in scoring offense in each of Maravich’s three seasons and never averaged fewer than 88.8 points per game. But for as potent as they were offensively, they were just as flimsy on defense, giving up between 87.5 and 89.4 points per game during Maravich’s career.

Maravich’s offensive philosophy and larger team-building approach had its share of critics at the time. George Smith, writing for the Anniston Star in Alabama, noted that “LSU’s offense is pretty simple – throw the ball in to 'Pistol Pete,' he dribbles the length of the court, and bangs away."

Other critiques cut a little deeper. In Mark Kriegel’s book “Pistol: The Life of Pete Maravich,” Les Robinson, who was an assistant under Press at N.C. State (and later went on to become the head coach of the Wolfpack in the late 1990s), was quoted as saying:

“He wasn’t the same coach I knew at N.C. State and he had already become obsessed with Pete’s numbers. He had gone from being one of the greatest coaches in the game to the coach of the greatest player in the game. That’s the only criticism I have of Coach Maravich: he loved his son too much.”

For folks of a certain age reading this, it wasn’t terribly dissimilar from a tactic employed in the TV show ‘Hey Arnold,’ when the titular main character played on a youth basketball team under a coach, voiced by Jim Belushi, who insisted that the only appropriate move to make on offense was passing the ball to his son, Tucker.

It’s the classic trope of a coach’s son, though in Maravich’s case, it’s not entirely fair. This was Pete Maravich, after all.

Despite his ludicrous output, though, LSU was never particularly excellent in any of Maravich’s three seasons. During that time, the Tigers went 49-35, topping out at 22-10 during Maravich’s senior season in 1969-70. That year, they missed out on what was then the 25-team NCAA Tournament and made it to the semifinals of the NIT. Considering they went 3-23 in Press’ first season, the one before Pete became a varsity eligible player, that’s commendable progress.

Over his 17 seasons as a Division I head coach, Press Maravich’s teams, the vast majority of which didn’t include his son, went 175-226. In only five of those seasons did his squad finish with a winning record.

Pete Maravich’s untouchable statistical resume

For whatever larger team success eluded him, and perhaps because of it, Maravich left behind a college resume that has nothing even remotely resembling a peer.

Here’s a quick rundown – or at least as quick of one as there can be – of statistical categories in which he ranks first in the NCAA record book:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Front Porch to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.