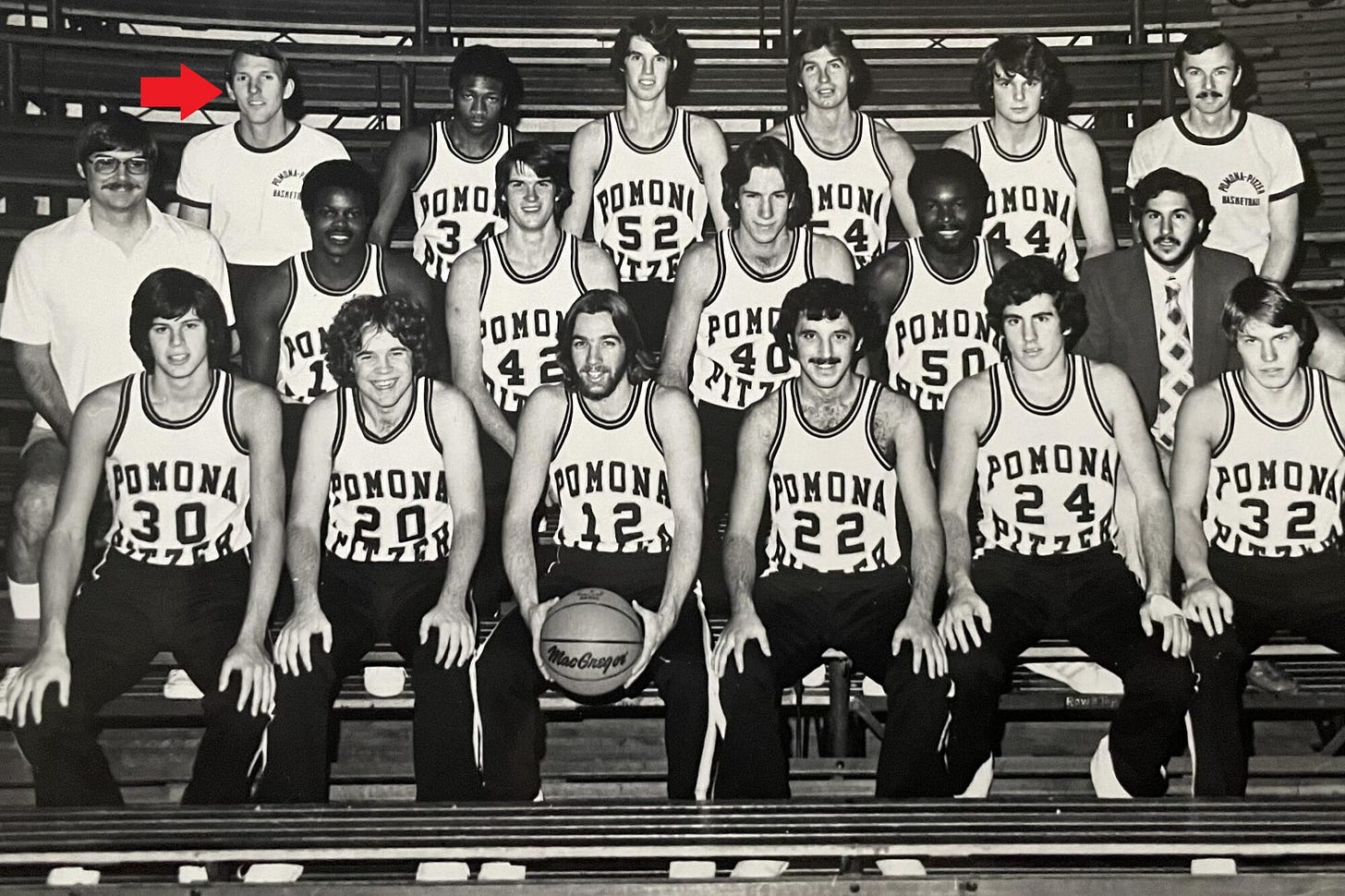

The journey of Gregg Popovich, Division III basketball coach

Long before the recently retired coaching legend led the San Antonio Spurs to five NBA titles, he was the coach at Division III Pomona-Pitzer

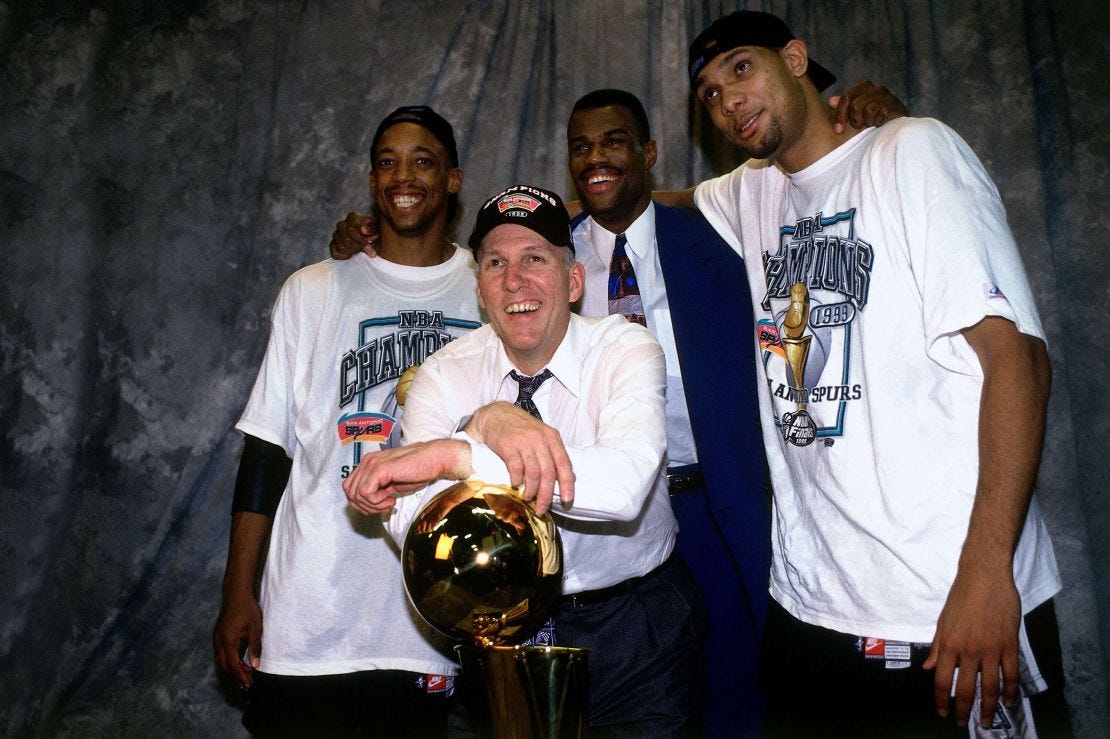

In Dec. 1996, then-San Antonio Spurs general manager Gregg Popovich made what would become one of the shrewdest moves in NBA history, firing coach Bob Hill after a dreadful 3-15 start to the season and inserting himself into the position.

You probably know what came next.

The Spurs became one of the longest-running and unlikeliest dynasties in NBA history, winning five championships over a 15-year stretch while experiencing significant roster churn and employing wildly different playing styles from their first title to their last. And at the head of it all was Popovich, the wise and wry basketball genius who cemented his place as one of the greatest coaches in NBA history.

On May 2, exactly six months after he suffered a stroke, Popovich stepped down after 29 seasons and 1,422 victories, ending one of the more accomplished and transformative runs leading a franchise in any American sport ever.

Perhaps more remarkably, he left the sideline having been a head coach at only two places – the Spurs and a Division III men’s basketball program east of Los Angeles.

Though Popovich didn’t become a household name and a Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Famer through his eight largely forgotten years coaching at tiny Pomona-Pitzer, his experience overseeing a college basketball program set the stage for everything that followed in his life and career.

Making something out of nothing

Nearly a half-century before he walked away from the Spurs, Popovich was in the news for a different kind of transaction.

In 1979 – after six years as an assistant coach at his alma mater, Air Force – a 30-year-old Popovich was named the head coach at Pomona-Pitzer, a hiring that was largely relegated to the agate pages or as a bullet point in notebooks in a small handful of California newspapers.

The school he arrived at, Pomona College, is one of the top liberal arts schools in the country, but it had an enrollment of just 1,400 students. It was so small that a decade before Popovich was hired, it had combined its athletic department with Pitzer College, a newer, decidedly crunchier liberal arts college less than a mile from its campus and a fellow member of the Claremont Colleges consortium.

For as academically rigorous as the schools were, and perhaps because of it, they didn’t exactly churn out great athletes. Players at Pomona-Pitzer didn’t just lack the size and girth of their Division I contemporaries – that’s to be expected at the Division III level, where excellent, albeit smaller, basketball is played – but they were, for lack of a better phrase, not very good. In a 1986 interview with the Los Angeles Times, Popovich likened his first team to an intramural club.

“On that team, we had maybe four or five guys who had been starters in high school,” Peter Osgood, a player on Popovich’s first team, said to Grantland in 2015. “Most of the team wasn’t even good enough for that.”

Given what he inherited, Pomona-Pitzer’s climb under Popovich would be slow, steady and arduous.

In 1979-80, Popovich’s first season, the Sagehens – yes, that’s their real name – went just 2-22, with the nadir coming in a loss to Caltech that snapped its 99-game conference losing streak and handed the Beavers one of just two conference victories they enjoyed between 1971 and 2011.

For much of the season, they struggled to have enough players for 5-on-5 scrimmages in practice as some members of the team had quit and, depending on the day, others were tied up with classroom obligations.

Recruiting proved to be a grind, albeit one Popovich embraced. Long before the days of easily accessible highlight reels, Popovich penned lengthy, personalized hand-written notes in which he’d discuss a prospect’s on-court goals and academic ambitions. He’d call them to talk about their classes and families. Popovich and his staff did all of this while having to identify potentially impactful players from an extremely small subset of the high-school-aged population – recruits who could conceivably compete at the college level, but also have the grades to get into a school as selective as Pomona or Pitzer, institutions that didn’t offer the same kind of admissions wiggle room that many of the most academically prestigious Division I colleges enjoy. They tried to rely on local high school coaches to guide them in the right direction, but were more than occasionally misled. As Jordan Ritter Conn described it in his 2015 piece in Grantland, the Pomona-Pitzer coaches were frequently recommended “star players with B averages or geniuses who could barely make layups.”

Through those missteps, though, Popovich found himself – or some version of the man so many of us have come to recognize over the past 30 years.

His acerbic wit was regularly showcased after tough, lopsided losses. After losing to Southern Miss by 36 in Dec. 1981, Popovich told the assembled media “I would have an IQ of 10 if I thought we could come in here and [win].” Two years later, following a 24-point loss at Portland in Nov. 1983, he said “No matter what the coach tells his kids, it had to be tough for them to get up for us.” The following month, after a 19-point loss to conference foe Redlands, he noted he couldn’t think of anything his team did well other than that it “had some nice music in the van ride over.”

Those remarks didn’t indicate a lack of appreciation for Pomona-Pitzer. Frankly, it didn’t take him especially long to fall in love with it and immerse himself in the broader community.

Early in his tenure, he lived in a dorm apartment with his wife and two children. He’d walk around the Claremont Colleges to look at various art installations. He and his kids would eat in the dining halls together. He attended lectures. He chaired a committee aiming to get rid of fraternities on campus. He’d hang out with professors to debate politics and philosophy over a glass (or several) of wine.

That communal feeling extended to his team. He’d have players over for meals. He’d write letters to parents praising their kids’ work. If he knew a benchwarmer’s parents were at a game, he’d make sure to put them in. He took an active part in a student manager’s senior class president campaign, plastering posters over campus for a race she ultimately won. He’d encourage his players to support other teams and events on campus, even having them man the snack stand at football games, a tradition that’s still active today.

“Slowly but surely, they took pride in the program and that worked,” Popovich said in 2020 to The Student Life, the student newspaper for the Claremont Colleges.

Gregg Popovich’s Division III breakthrough

Over time, the Sagehens’ fortunes improved.

They went from 2-22 in Popovich’s first season to 10-15 in his second and finished .500 in their conference in his third season. The program’s trajectory was decidedly up, in part because of some of the skill its young coach had displayed in getting it there.

In a cold-hearted-but-ultimately-effective move, Popovich made every player from his first team try out to be a part of his second, with only two making the cut. He’d bring in more freshmen than he realistically would have needed, if only to increase his odds of stumbling upon a hidden gem or two. He formed a JV program, giving Pomona-Pitzer some much-needed depth and a developmental pipeline. From his first year to his second, the team’s average height rose three inches, from 6-foot-2 to 6-foot-5.

His tactical brilliance was put on display, too, often due to desperate circumstances. In those 4-on-4 scrimmages in his first season, he realized the Sagehens played better with two fewer players on the court at a given time, opening up lanes and spacing the floor. With not much to lose, he decided to try it out in a game, having four players come up the floor on offense while one lagged behind near midcourt, bringing a defender out to keep an eye on him. They’d play a four-out offense with nobody in the post and even when teams adjusted to bring the fifth defender into the fold, Pomona-Pitzer would have their wayward fifth man jump into an open spot at an opportune moment, transforming their offense from a horrid unit to something significantly more passable.

“He was pulling rabbits out of a hat,” Osgood said to Grantland. “He was like a magician, trying to find any way to make us good.”

Though he was sometimes led astray, Popovich remained a relentless recruiter, following every tip he got and every so often striking gold, just as he did with 6-foot-5 forward Dave DeCesaris from Riverside Community College, who chose Pomona over several Division I offers and went on to set most of the Sagehens’ all-time scoring records.

He benefited from a supportive administration, which is seldom a given at Division III schools where sports play a significantly smaller role in campus life. Specifically, there was Pomona’s dean, Bob Voelkel, a former Division III All-American basketball player who liked athletics and aimed to foster the success of his school’s teams.

During the 1985-86 season, Popovich’s seventh at the helm, those years of hard and diligent work came together for a run that Pomona-Pitzer had never seen to that point.

With DeCesaris leading the way averaging 22 points per game, the Sagehens won their league, the Southern California Intercollegiate Athletic Conference, outright for the first time in 68 years. That earned them a spot in the NCAA Tournament, where they were blown out 89-59 by Nebraska Wesleyan in a game that Popovich told reporters “didn’t think that this would happen in my worst nightmare.”

Still, a group that he described before the tournament as “one talented person and 10 overachievers” reached a point few, if any, would have imagined two years earlier, let alone when Popovich was hired.

“We didn’t really care [about the NCAA Tournament loss,” Popovich said to The Student Life. “We’d have rather won, but we were so excited about winning the conference championship for the first time in so many years that it didn’t even feel like a loss.”

The invariable exit

After that run, the gears that led Popovich to basketball immortality were put into motion.

With the encouragement of Pomona athletic director Curt Tong, a former Division III coach himself, Popovich took a sabbatical. Rather than going abroad somewhere or taking time away from the game to avoid burnout, Popovich got a basketball education in which he was able to view the game through a lens that was previously unavailable to him.

While still a player in the early and mid-1970s, Popovich developed a relationship with legendary coach Larry Brown, who was twice a part of staffs that cut Popovich – first for the U.S. men’s national team for the 1972 Summer Olympics and then again in 1975 while Brown was the head coach of the Denver Nuggets, then of the ABA.

The two stayed in touch and following the 1985-86 season, Popovich went to learn under Brown. He spent October and November of the 1986-87 season at North Carolina, Brown’s alma mater, under Dean Smith before going through the rest of the season with Brown and Kansas, serving a key role on the Jayhawks’ bench and coaching a group of players, most notably Danny Manning, that would lead the program to the NCAA championship the following season.

Eventually, his heart led him back to Pomona-Pitzer.

“I’ve been spoiled at North Carolina and Kansas,” he said to the Los Angeles Times in 1987. “When I get back to Pomona, I’m going to have to be careful not to be someone else other than me. I know I’ll be more efficient and I’ll have a computer bank of knowledge that should help my teaching techniques. I’d be a fool to say it isn’t a thrill to watch and help players of Division I caliber develop into great players. But I think at this point, the small-college level is the place to be if you want to coach and not have droves of people who want a piece of you. That’s more consistent with my personality.”

In his brief time away, though, circumstances had changed. Shortly after Popovich got back to Pomona-Pitzer, Voelkel died and school leadership that succeeded him wasn’t as invested in his program’s success. By the end of the 1987-88 season, he began thinking of life away from the community he loved.

While at a cabin in the summer of 1988, news broke that Brown, months after leading Kansas to the national title, had been named the Spurs’ head coach. One of his assistants, Lee Wimberly, suggested Popovich call him to see if he’d bring him along to San Antonio. Popovich had his doubts.

“He thought Larry Brown was going to laugh in his face,” Wimberly said to Grantland.

What followed, as they say, is history, with Popovich spending four seasons with Brown in San Antonio, leaving to work as an assistant under Don Nelson for two years with the Golden State Warriors and returning to the Spurs to become their president of basketball operations and general manager in 1994.

Even with everything that followed, Popovich never strayed far from Pomona-Pitzer, mentally or emotionally.

Though he owns the worst overall win percentage (.380) for a coach in program history, he took the Sagehens to heights they’d never previously enjoyed. One of his assistants, Charles Katsiaficas, took over for Popovich in 1988 and remains the head coach there today. He’d routinely invite groups of his former players to come to San Antonio, with all their expenses paid for them. He’d keep in touch with players and lend an ear to discuss their lives, families and careers. Whenever Pomona-Pitzer would play Trinity University, a private liberal arts school in San Antonio, Popovich would try to make it over there to watch the game and speak with the team.

For Popovich, Pomona-Pitzer wasn’t a stepping stone on a path to inevitable basketball glory, a pitstop that had to be endured to enjoy the fame and riches that came next. When he left in 1988, he told the Los Angeles Times that becoming an NBA coach wasn’t something he ever envisioned and that for as delighted as he was with the opportunity, he was “scared to death.”

Those fears never swallowed him and likely only took so long to disappear entirely, but the memories of what he left behind in southern California stayed with him.

“I just thought it was an opportunity of a lifetime,” he said to The Student Life. “I miss it. I always say that I’m faking it as an NBA coach because at heart, I’m a Division III coach through and through.”

My favorite things I read this week

I’ve been battling a cold for much of the past week, which came with a lighter reading load (and a delayed publishing date for the Popovich story), but here’s what stuck with me the most:

Anelise Feldman, a freshman at Yarmouth High School in Maine, finished second in a 1,600-meter race to a trans competitor, wrote a letter to the editor of the Portland Press Herald to offer a thoughtful, empathetic and extraordinarily mature response a state house representative for using the case for publicity

CJ Moore and Brendan Marks over at The Athletic wrote an interesting piece on why we’re seeing this influx of European professional players coming into college basketball (similar to the Illinois story from last week)

This one’s more out of morbid enjoyment, but I stumbled across a 2016 column from Bernie Lincicome of the Chicago Tribune lamenting Lamar Jackson’s impending Heisman Trophy victory. He described the future two-time NFL MVP as someone who “remains favored to be as forgettable as Eric Crouch.” We all, myself included, have bad, hilariously wrong sports takes, but whew, that’s a different level.

(Photos: Pomona College, Sports Illustrated, Getty Images)