The College Football Hall of Fame bent its rules for Mike Leach. It needs to do the same for Howard Schnellenberger

The Hall's win percentage requirement is keeping out one of the best coaches in the sport's history

An update on a story from last year: On Thursday, while Donald Trump and Elon Musk’s high-profile split was escalating seemingly every second, with Musk saying Trump is in the Epstein Files and Steve Bannon demanding Musk be deported, Jon Rothstein tweeted that Iona and Fordham had agreed to a home-and-home series in men’s basketball. Perhaps his finest work yet.

Now, on to the latest newsletter…

The National Football Foundation announced late last month that it had tweaked a piece of eligibility criteria for the College Football Hall of Fame, lowering the required win percentage for coaches to be inducted from .600 to .595.

The adjustment opened the hall’s hallowed doors to several prominent coaches, including Jackie Sherrill and Les Miles, but discussion of the decision centered largely around one figure – Mike Leach.

Leach is one of the most important figures in college football over the past 30 years. To call him a revolutionary wouldn’t be hyperbole. He helped popularize the Air Raid offense, using the spread-out, pass-happy scheme to light up scoreboards and, in a copycat sport, inspire programs from across the country to try to emulate it, particularly within the conference in which he first rose to prominence, the Big 12. Nearly three full years after his death, his fingerprints are still all over college football, from teams employing Leach-like schemes to his extensive coaching tree, which includes Lincoln Riley, Josh Heupel, Sonny Dykes and Dave Aranda.

He not only changed the sport, but he won at college football outposts like Texas Tech, Washington State and Mississippi State, most of which hadn’t been all that accustomed to the kind of sustained success he brought. Given the kind of historically middling, resource-deficient places where he coached, though, Leach’s career win percentage is just .596, which previously barred him from Hall of Fame consideration.

That has now changed, though, a move that is rightly being celebrated across the college football world.

"I don't know that anybody has had as big an impact on the game of football, whether it's college football, pro football, high school football, than Mike has,” Dykes said to ESPN. “He's certainly deserving of the Hall of Fame. I don't think that the Hall of Fame needs to be exclusive to coaches that have coached historically very successful programs. Mike did a great job of taking programs over and getting those programs to the highest level that they've ever performed at. So I'm excited for him. He certainly deserves it. It's a real credit to him and to what he's meant to college football that they reconsidered their model."

What has been widely billed as a solution, though, still has its problems – namely, that the type of coach that Dykes described is still being excluded from the Hall of Fame, even with the recent change.

Among that group, there’s one that’s especially glaring.

Howard Schnellenberger: college football’s ultimate program builder

Many of the same bullet points that make Leach’s resume resonate in the way it does also apply to Howard Schnellenberger.

An offensive innovator who changed the way programs around the country operated schematically? Check.

A masterful tactician who was able to win at places where few others had? Yes.

An eccentric personality who helped make the sport more interesting? Absolutely.

If anything, Schnellenberger has a more compelling case for induction because he has something that Leach doesn’t (and never came particularly close to getting) – a national championship.

Like Leach, Schnellenberger has a surprisingly low career win percentage for someone who’s as widely respected as he is, at just .514 at the FBS level. Unlike Leach, though, it will take more than just shifting a statistical benchmark a few hundredths of a percentage point.

Leach’s impending induction into the Hall of Fame, and the series of moves that will have made it possible for him to get there, is worth celebrating, but it’s also an opportunity to reexamine the National Football Foundation’s criteria and who it’s harming.

Perhaps no coach has been more negatively and unfairly impacted by it than Schnellenberger, who lifted two current Power Four programs into what they are today and built another entirely from scratch while showing why he’s one of the best, if not most overlooked, coaches in the sport’s history.

Before he even became a college head coach, Schnellenberger was an integral part of Bear Bryant’s early success at Alabama. In five years working as the offensive coordinator for his former college head coach, Schnellenberger helped lead the Crimson Tide to three national championships and recruited the likes of Joe Namath and Ken Stabler.

From there, he went on to win national titles far more improbable than the ones he racked up as part of Bryant’s Alabama machine.

When Schnellenberger arrived at Miami as the program’s new head coach in 1979, the Hurricanes weren’t anything close to the college football power they are today.

Miami had been plagued by constant turnover, with Schnellenberger becoming the seventh coach in a 10-year stretch at the school. Its on-field product suffered as a result, with the Hurricanes going 14-29 in the four seasons before he got there. Even before that period of instability, they weren’t a particularly impressive outfit, with only two bowl wins in 27 years. After Schnellenberger’s immediate predecessor, Lou Saban (no relation to Nick), left Miami to become the head coach at Army, a festering debate on whether to drop the football program down to Division I-AA or eliminate it entirely was reignited among university power-brokers. John Green, the school’s executive vice president, successfully convinced the board of trustees to give Division I-A football one more shot.

Even that vote of faith, though, did little to improve what were less-than-ideal conditions under which the program was trying to compete.

“There were no facilities,” Schnellenberger said to journalist Bruce Feldman in his book Cane Mutiny. “There wasn’t even a place to hang a jockstrap.”

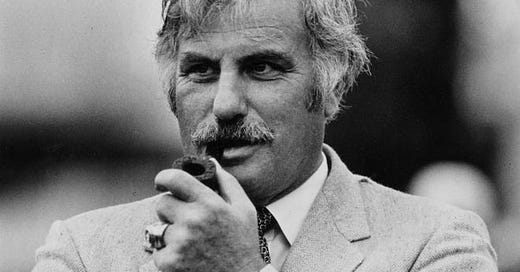

Under their swaggering, gruff-voiced, pipe-smoking new coach, their fortunes soon changed.

Schnellenberger implemented a pro-style passing attack that stood in stark contrast to the prehistoric, run-heavy schemes that the nation’s top programs employed at the time. He and his staff went all-in on local recruiting in talent-rich south Florida, labeling anything south of Interstate-4 as “the State of Miami.”

Beyond that intense geographic focus, the way Schnellenberger’s Miami program recruited changed the sport. Schnellenberger would go directly to the homes of top local prospects, many of whom lived in some of the city’s poorest neighborhoods. As was mentioned in “The U,” the 2009 ESPN documentary on the rise of Miami football, it would have been unheard of for Joe Paterno or Lou Holtz to make a trip to Overtown or Liberty City just to speak to a recruit. By doing so, Schnellenberger connected Miami, a private school derisively known at the time as “Sun Tan U” for its reputation of being a haven for academically underachieving kids of rich northeastern families, to the broader community it called home. It paid off tremendously, luring in the area’s highest-rated recruits and building generations of new fans.

His plan came to fruition in a way few could have anticipated. In his just second season, the Hurricanes went 9-3 and won their first bowl game in 14 years. Even bigger accomplishments awaited. After promising to win a national championship within his first five years at Miami, he did just that, with his fifth Hurricanes team winning the 1983 national title after an Orange Bowl victory against an undefeated Nebraska team that was being openly discussed at the time as the greatest in college football history.

Five months later, he left Miami to take over a USFL franchise, the Washington Federals, that was planning to move to Miami, but the relocation never materialized and Schnellenberger was out of a job.

Still, his mark had been made. His 1983 Miami team was the catalyst of a dynasty, with the Hurricanes winning championships in 1987, 1989 and 1991 under Schnellenberger’s successors, Jimmy Johnson and Dennis Erickson.

“I believe in my heart and soul that if he had stayed here, he would have been the most legendary coach in the history of football,” Art Kehoe, a longtime Miami assistant, said in “The U”. “He would have won so many national championships, it would have been staggering.”

Schnellenberger spoke of his decision to leave Miami with regret, but in many ways, it was fitting with what his identity as a coach became. As Rick Bozich, a longtime sports writer in Louisville, wrote, Schnellenberger’s “indomitable spirit was driven by accepting challenges that made other coaches flinch.”

That next challenge awaited him at Louisville, where he grew up.

While the school’s men’s basketball program was in the middle of a storied run under coach Denny Crum, the football program was languishing. It went 5-17 in the two seasons before Schnellenberger’s arrival and had just two winning seasons in the previous 12 years. It played in front of sparse crowds in a minor-league baseball stadium at the state fairgrounds, with local gas stations giving away free tickets to patrons who filled up their cars. As it was at Miami in the late 1970s, the Cardinals had been considering a drop to the Division I-AA level.

Unlike Miami, it took Schnellenberger a little bit to get things going. Louisville went 8-24-1 in his first three seasons before a breakthrough 8-3 campaign in 1988. From there, he guided the program to heights it hadn’t previously enjoyed. In 1990, the Cardinals went 10-1-1 and throttled Alabama in the Fiesta Bowl to finish the season 14th in the Associated Press poll, which stood as their highest finish in their first 41 seasons at the Division I-A level. It capped off a three-year stretch in which they went 24-9-1. Three years later, they went 9-3 and won the Liberty Bowl, giving them two bowl victories in four seasons at a place that had been to only two bowls in the 23 seasons before Schnellenberger took over (neither of which they won).

Though he never got close to the “collision course with a national championship” he promised when he was hired, Schnellenberger’s impact at Louisville, like Miami, was perhaps more evident than ever after he had left. The Cardinals made eight consecutive bowl games from 1998-2006, the last of which came in a season in which they were a second-half collapse against Rutgers away from an undefeated season and a likely national championship game berth. In 1998, they opened a brand-new stadium, fulfilling the vision for a project Schnellenberger pushed for throughout his tenure. In 2012, they were accepted as members of the ACC, completing a meteoric rise up from lowly Conference USA, and four years later, they produced a Heisman Trophy winner.

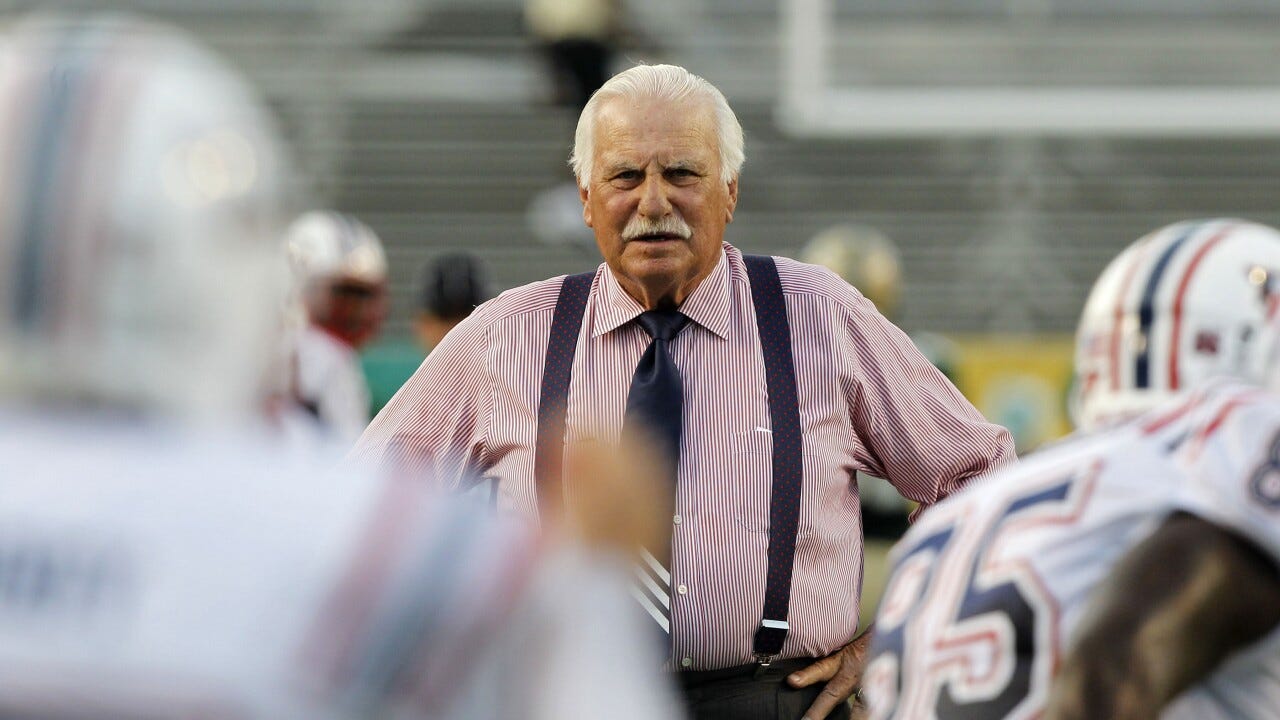

While Schnellenberger’s first two college coaching tenures were rebuilds, his final one was just a straight-up build.

Following a forgettable, ill-fated one-year run at Oklahoma in 1995, he was recruited in 1998 to be the director of football operations for the soon-to-be-launched football program at Florida Atlantic. The 64-year-old was tasked with coming up with a strategic plan, raising funds and selecting a coach. He did all three, getting $13 million worth of donations and assistance from the state legislature. When it came time for picking a coach, he had just the person in mind – himself, pulling a Dick Cheney one year before the phrase’s namesake did the same.

The program began practicing in 2000, with 160 walk-ons and 22 scholarship players, and had its first season in 2001. The Owls’ first game, a 40-7 loss to Slippery Rock, was an early indicator that the program’s nascent years would be difficult, but by 2003, Schnellenberger’s third season at the helm, they went 11-3 and made the Division I-AA semifinals. They made the jump to Division I-A the following season and made back-to-back bowl games in 2007 and 2008, both of which they won.

Whether it’s a testament to how extraordinary his early work was or a sign that he didn’t build something as sturdy as he did at Miami and Louisville, Florida Atlantic has made just three bowls in the 13 seasons since Schnellenberger retired after making two in its first five FBS seasons.

"This one is so different," Schnellenberger said in 2011 to Pat Forde, then of ESPN. "The others, we were working with adopted kids. These were our kids. We went from foreplay -- I think I can use that term these days and not get in trouble -- to conception to birth. It's been a great romance and it's produced, I think, a wonderful child."

Why does the College Football Hall of Fame have a win percentage requirement for coaches?

For all the eternal glory they represent, halls of fame are inherently arbitrary.

Baseball’s perhaps the most obvious example, where certain players alleged to have taken performance-enhancing drugs are in while others aren’t and players’ assholeishness and bigotry can be excused if their hall-of-fame credentials are undeniable (which is why someone like Ty Cobb is enshrined in Cooperstown and Curt Schilling isn’t).

But even in a sport like college football, where some statistical barometers are applied for entry, it’s hardly scientific.

For one, there 32 coaches already in the College Football Hall of Fame who had sub-.600 career win percentages. The College Football Hall of Fame’s Honors Review Committee, which could have circumvented the National Football Foundation criteria and let Schnellenberger in years ago, hasn’t existed since 2012.

The guidelines a coach has to meet to be inducted – having coached for a minimum of 10 years and coached at least 100 games with a .600 winning percentage – are hardly an accurate gauge of how good they were at their jobs. With the win percentage threshold now lowered to .595, here’s a sampling of some of the coaches who meet those marks:

Bryan Harsin (.702)

Larry Coker (.667)

Paul Chryst (.656)

Tommy Bowden (.647)

Hugh Freeze (.623)

Tommy Tuberville (.616)

Dave Doeren (.615)

Clay Helton (.606)

Paul Pasqualoni (.603)

Kevin Sumlin (.601)

Ralph Friedgen (.600)

Todd Graham (.596)

All of these men were perfectly fine coaches – you don’t amass that kind of a win percentage without being one – but they’re hardly what you’d consider hall of fame material. It’s especially egregious given who’s on the ballot this year. Coker, whose tenure at Miami marked the start of the program’s decline from its dynastic days, is on there. So is Tuberville, whose shortcomings go beyond his shitty politics and speed-limit IQ. In the latter part of his career, he was something of an anti-Schnellenberger – taking over thriving programs others had built up at Texas Tech and Cincinnati and torpedoing them. Yet he has a path to get in the hall of fame that has been denied to Schnellenberger, who died in March 2021 at the age of 87.

It raises an important question: while the recent accommodation for Leach is commendable, why is there even a win-percentage threshold at all? Perhaps there’s a sound, justifiable and overlooked rationale behind it, but it seems like a solution that causes more problems than it fixes (for what it’s worth, I reached out this week to the National Football Foundation for clarification on the rule, why it was instituted and how long it has been in place, but I never heard back).

Because of it, one of five coaches since the end of World War II who has won a national title at a program that had never previously finished a season in the top five of the AP poll isn’t in the sport’s hall of fame. As you might have guessed, the other four are.

Schnellenberger is the face of this issue, but there are others like him who are impacted by it. Joe Tiller used an ahead-of-its-time, pass-heavy offense to make Wyoming a top-25 team and lead Purdue to nine bowls in 11 seasons – including the school’s second-ever Rose Bowl appearance – but his career win percentage is just .578. There’s also Sonny Lubick, a defensive coordinator for two Miami national championship teams who turned Colorado State into an unlikely powerhouse, with the program’s only three top-25 finishes ever, all of which came in a seven-season span from 1994-2000. He falls even more painfully short of the win percentage threshold, at .593.

For all of these men, but especially for Schnellenberger, the history of college football is incomplete without including them. How can you explain Miami’s unlikely and polarizing run in the 1980s and 1990s without mentioning the man who started it all, to say nothing of other facets of the game he helped mainstream?

There’s that famous old line from Groucho Marx in which he said that he wouldn’t want to be a member of a club that would accept him as a member. In the case of the College Football Hall of Fame, it isn’t fulfilling its mission or purpose if it continues closing to shut out one of the most consequential figures to ever roam a sideline.

My favorite things I read this week

Ken Goe, writing for The Oregonian, looks at the potentially dire future for track and field in the post-House settlement world of college athletics

- of the excellent Buzzer newsletter writes about college basketball’s most interesting and confusing rosters heading into next season

Israel Daramola at Defector examines the disappearance of the cool athlete in major American sports, particularly the NBA, which has teams led by Shai “What a Pro Wants” Gilgeous-Alexander and Tyrese Haliburton

This excerpt from Mark Kriegel’s recently released Mike Tyson biography is only making me more excited to buy it

Next month, Clipse is coming out with its first studio album in 16 years and this feature from Frazier Tharpe of GQis making it feel that much more real and thrilling

(Photos: Associated Press, Miami Herald)