Revisiting Suge Knight's college football career

With UNLV suddenly one of the major topics in the world of college football, let's take a look back at one of the Rebels' most famous (or infamous) alums

During a week that culminated with an instant classic between two of the sport’s preeminent powers, Alabama and Georgia, the dominant storyline in college football centered around UNLV.

In the early stages of what could be a transformative season for the program, with an undefeated record, a high-powered offense and a top-25 ranking in the Coaches Poll, the Rebels lost one of their most important players when quarterback Matthew Sluka announced he was redshirting and sitting out the rest of the season because his agent claimed the school didn’t come through on a verbal promise for $100,000 for the Holy Cross transfer.

As UNLV wrestled with its role in the latest national debate over name, image and likeness, it was weighing one of the most consequential decisions in the athletic department’s history – whether to join the Pac-12 or remain in the Mountain West, with their choice bolstering one conference and sending the other into an existential crisis. Ultimately, they opted to stay in the MWC, preventing what would have inevitably been a painful bleeding of its most desirable remaining members.

UNLV earning a rare spot in the college football spotlight got me thinking of something else, though – or, more specifically, someone else.

From Compton to Vegas

Now that I’m no longer a beat writer and don’t have to spend so many of my waking hours on it, I primarily use Twitter for jokes, the kinds that I and maybe a handful of other depraved individuals scouring that digital wasteland find funny. If nothing else, it’s a way to lighten things up on a website that’s rapidly devolving into a haven for neo-Nazis and an advertising platform for crypto and other, more noble endeavors, like various internet scams.

As people were scrambling to make sense of Sluka’s decision, what led to it and the ramifications of it, I turned to the only thing I ever really think of whenever the subject of UNLV football comes up.

I’m talking, of course, about Suge Knight.

(I realize now this is my third newsletter over the past four months in which Knight has at least been referenced. I have no idea how we got here, but I will not apologize for the repetition.)

A handful of years before he became Death Row Records’ notorious and imposing co-founder and CEO – a man who intimidated everyone in an industry filled with people who don’t easily get intimidated – Knight was a football player whose athletic talents brought him from the streets of Compton to UNLV and the gridirons of what’s now known as the Football Bowl Subdivision.

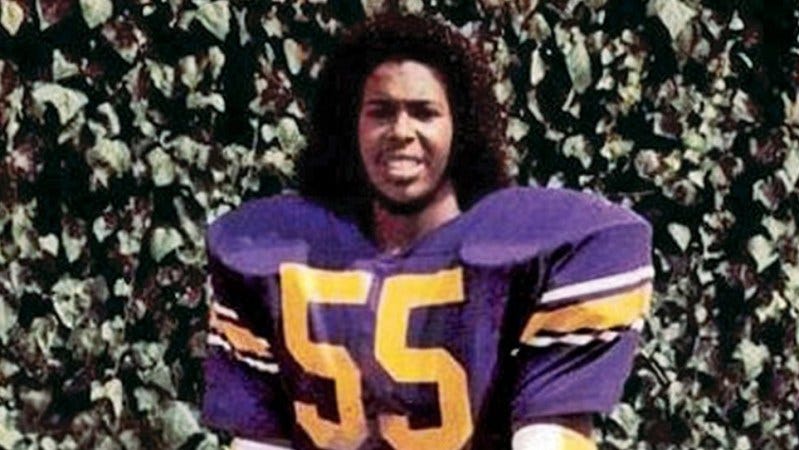

At the time, he was simply Marion Knight, a promising defensive lineman who enrolled at El Camino Junior College in his native southern California. Known affectionately as “Sugar Bear” by those close to him, a childhood nickname that was eventually shortened to “Suge,” Knight caught the attention of UNLV coach Harvey Hyde, who was stopping by the school as part of a recruiting trip in the mid-1980s. Impressed by what he saw from the defensive lineman with the big, quintessentially 80s hair, he convinced Knight to pack his bags for Las Vegas despite knowing Knight had an affiliation with the Bloods, who controlled his neighborhood in Compton.

While still known overwhelmingly as a basketball school, the Rebels weren’t completely devoid of tradition when Knight arrived there ahead of the 1985 season.

Ron Meyer (no relation) coached there for three years in the mid-1970s, including an undefeated regular season in 1974, before taking the same job at SMU, where he recruited the “Pony Express” backfield of Eric Dickerson and Craig James and, wisely, bounced for the NFL before the shit truly hit the fan at the school and the Mustangs were handed the death penalty by the NCAA. In 1978, UNLV made the jump to the Division I-A (now FBS) ranks. The season before Knight joined the Rebels, they went 11-2 behind a quarterback who quickly became famous well beyond that corner of Nevada – Randall Cunningham.

As anyone in the music business learned in the early 1990s, Knight was a physically domineering man, listed officially at 6-foot-2 and 260 pounds. Admittedly, I was a bit surprised to see he was only 6-2 – that’s how tall I am, after all – but it makes a little more sense when you realize Tupac Shakur, the man he’s perhaps most commonly pictured alongside, was only 5-foot-9.

Once at UNLV, he quickly put that frame to good use.

As a junior in 1985, he was UNLV’s rookie of the year, was named defensive captain and picked up first-team all-Pacific Coast Athletic Association honors. Following that season, Hyde was dismissed after a string of off-the-field incidents involving his players, a list of offenses that included burglary, the beating of an off-duty policeman, embezzling video and stereo equipment, sexual assault and domestic violence.

In 1986, his second and final season with the Rebels, Knight finished with 7.5 sacks, a mark that still ranks him ninth in program single-season history. He was again a first-team all-conference recipient and even got an Associated Press honorable mention all-American nod.

At times, he displayed the aggression and poor judgment for which he would eventually become known, like when he got into it with new UNLV coach Wayne Nunnely after Knight was flagged for a late hit in a 34-14 loss to Washington State to open up the 1986 season.

“We’re trying to change our attitude as far as being a team that plays within the rules,” Nunnely said after the game, according to the Spokesman-Review in Spokane, Wash. “Dead-ball fouls are not very smart. Those are things we have to take care of – and will take care of.”

Beyond incidents like that, the impression Knight left on those around him was largely positive. Unlike a number of UNLV players from that time, Hyde told ESPN’s The Undefeated in 2017 that Knight “never, ever gave me a problem in any way.” Despite that initial rockiness in his first season, Nunnely told the Las Vegas Sun in 1996 that Knight “wasn't a problem guy at all” and that “you didn't really see that street roughness about him.”

Following the September 1996 shooting of Shakur in Las Vegas, an incident that took place a relatively close walk away from UNLV’s campus, Knight’s college football career came into focus once again, 10 years after he played his last snap. Knight was grazed by a bullet and Shakur was hit four times in the chest, injuries that ultimately killed the legendary rapper six days later.

Media outlets seeking perspective on Knight and his two years with the Rebels encountered coaches and others who spoke of him in a way a neighbor or former classmate might speak about a mass shooter – someone who presented one way to them, but clearly had something much darker lurking inside of them.

"It's been 11 years and I really don't know much [about Knight's life] after [football],” Hyde said to the Las Vegas Sun. "He played for me and he gave me 100 percent, and that's the thing I judge a man by."

Others who were farther away from the football field witnessed other sides of Knight.

In that 2017 piece in “The Undefeated,” former Death Row Records publicist Jon Wolfson relayed a conversation he had with Knight in which the music impresario spoke of a scheme he had in college in which he would tell coaches he lost his books, be gifted new ones and then resell them for extra cash. In Randall Sullivan’s 2003 book “LAbyrinth,” Knight is painted as being more detached in his second and final season at UNLV, having moved into an apartment by himself and having friends from back in Compton visiting more frequently.

Perhaps the clearest indication that a violent future awaited Knight was that he excelled in an extremely violent game.

“I think the most important thing, when you play football,” Knight said in an interview with comedian Jay Mohr in 2001, “you get the quarterback, you stick your hand in his helmet and peel the skin back off.”

Life after football

Knight’s college success didn’t translate into much once dropped out of UNLV shortly before graduation.

He wasn’t among the 335 players selected in the 1987 NFL Draft and after being invited to the Los Angeles Rams’ training camp that year, he was eventually cut. He later found his way onto the Rams’ roster, but it was as a scab during the 1987 players’ strike. He played in two games for Los Angeles and while no official stats exist of Knight’s brief NFL career, internet sleuths have determined that in the two games he played, against the Pittsburgh Steelers and Atlanta Falcons, he was on the field for eight plays and had no sacks, no tackles and one penalty

.Once the strike was over, so were Knight’s professional football dreams.

He still had a football player’s physique, though, allowing him to work his way into the world of entertainment. He was a bodyguard for stars like singer Bobby Brown and by 1990, he was promoting hip-hop shows in Los Angeles. He soon found himself in the inner circle of LA rap royalty like Dr. Dre, Ice Cube and Eazy-E. In 1991, he partnered with Dre to form Death Row, a move that only came after Knight and some of his cronies allegedly threatened Eazy-E and N.W.A manager Jerry Heller with lead pipes and baseball bats to coerce them into letting Dre and The D.O.C. out of their contracts with Ruthless Records, the label under which N.W.A released what would be their only two albums, including the 1988 classic “Straight Outta Compton.”

Death Row not only had Dre under its umbrella, but also Shakur and the man then known as Snoop Doggy Dogg. By the time Shakur was murdered, the label had moved more than 15 million records and raked in more than $100 million, making it the biggest rap label in the world. Knight had even grander goals for it, too, believing it could be to hip-hop what Motown was to pop music in the 1960s.

That work was seldom without controversy. Knight racked up a lengthy rap sheet filled with a slew of serious charges and admittedly more humorous ones, like allegedly grabbing Vanilla Ice by his ankles and dangling him over a balcony to force him to sign over the rights to his hit song “Ice Ice Baby,” which had been co-authored by a client of Knight’s.

Knight is currently in prison in San Diego, where he won’t be eligible for parole until Oct. 2034 after he pleaded no contest to voluntary manslaughter in 2018 following a 2015 incident in which he ran his car into two men, killing one of them, and fled the scene.

As he rose to fame and power, aspects of his UNLV days never totally left him.

He would regularly go to Las Vegas with friends and associates, particularly for high-profile boxing matches (Shakur was killed in the hours after a bout between Mike Tyson and Bruce Seldon.) He bought a house in Las Vegas that was used in the filming of the 1995 movie “Casino.” The house was red, though that could be attributed just as much to his ties to the Bloods than his two-year stint in the trenches with the Rebels.

If he does happen to keep up with UNLV football from behind bars, he’s undoubtedly been encouraged by what he has seen. In a season that had already included wins against a pair of Big 12 teams in Kansas and Houston, coach Barry Odom’s Rebels moved to 4-0 Saturday with a 59-14 thrashing of Fresno State in the team’s first game without Sluka. It’s a small sample size, but it’s a persuasive piece of evidence that maybe the program will be just fine this season with someone other than Sluka and his 43.8% completion percentage under center.

If his absence was glaring and the Rebels had lost, though, perhaps UNLV could have enlisted the help of one of its own to rectify a messy situation. It might have turned out better for Sluka than it did Vanilla Ice.