Louisville is falling in love again with its basketball team

After an unthinkably poor rut turned them into a doormat, the Cardinals have orchestrated one of college basketball's biggest turnarounds. And its hoops-mad hometown has taken notice

Over the course of his life, Mike Rutherford has watched his beloved Louisville Cardinals compete in some of the biggest, most pressurized moments men’s college basketball has to offer.

The Louisville sports radio host and longtime publisher of the wonderful website Card Chronicle has seen them complete double-digit comebacks to make it to the Final Four. He has suffered through some of the heartbreak that March has to offer. He watched them hoist a national championship trophy, a memory that not even the NCAA can take away from him.

Back in July, though, he found himself wrestling with nerves over something else entirely – a summer exhibition game in the Bahamas.

On the heels of a 12-52 record and back-to-back last-place finishes in the ACC from 2022-24, Louisville hired Pat Kelsey as its next coach, making an otherwise forgettable scrimmage against a team called “Bahamas Select” a more-important-than-usual beginning of a new era in the program’s history. The kind of anxiety that was once there for fans like Rutherford when a title was on the line was now present because of a looming question that went beyond just a single exhibition – is this thing that I love so much going to be OK?

He quickly got his answer. On their opening possession, the Cardinals played with a purpose, constantly moving on offense, communicating and delivering crisp passes. They finished the sequence off with Kasean Pryor, their transfer center who looks like a seven-foot Pete Davidson, calmly draining a 3-pointer.

And with that, the nerves started to fade.

“The fan base was desperate to see something tangible that they could hold on to and say ‘I know this is going to work whether it’s this year or some time down the line because of this,’” Rutherford told me. “Watching that team go out there against very overmatched competition, but still play with an edge, still play hard, still have an offensive and defensive philosophy that could translate to the actual games that started being played in November and December was incredibly encouraging. That was the moment where I was like, alright, I’ve gone from I don’t know what to expect from this team to kind of thinking this could easily be an NCAA Tournament team. It was really, really encouraging. And maybe more relieving than encouraging.”

Seven months later, that relief is now ecstasy.

In its first season under Kelsey, Louisville has been one of the biggest, most pleasant surprises in college basketball. With two regular-season games remaining, the Cardinals are 23-6 and in a tie for second place in the ACC standings, having already secured a double-bye to the conference tournament later this month. They’re widely considered a lock to make the NCAA Tournament, a destination they haven’t reached in six years.

Making the Big Dance was once an annual expectation for Louisville, not a cause for celebration, but that was before one of college basketball’s most historically decorated programs sunk to unimaginable lows over the past several years, with off-court scandal under Rick Pitino giving way to on-court futility under Kenny Payne, with Chris Mack’s puzzlingly disappointing four-year tenure wedged in between.

Now, the joy that was painfully absent for much of the past decade is starting to come back. A wholesale rebuild of the Cardinals that Kelsey has dubbed the “ReviVille” has been one in more ways than one.

How a college basketball powerhouse became a laughingstock

Louisville is proudly quaint, a place that’s statistically large but spiritually small.

It’s one of the 30 biggest cities in the country – with a population larger than Atlanta, Miami and Minneapolis, thanks to a consolidated city-county government – but it’s the kind of town where a long-ago-shuttered department store is used as a landmark when giving directions and where one of the first questions someone is asked when meeting a stranger is where they went to high school.

In the absence of the professional teams surrounding cities like Cincinnati, Nashville, Indianapolis and St. Louis have, the collective fixation of everyone in Louisville falls on college sports. While the city has its share of Kentucky fans, much of that passion and interest is channeled to the Cardinals – and, specifically, their men’s basketball program.

For much of Louisville’s history, it has been a symbiotic relationship. The persistent, previously unshakeable interest filled palatial arenas. It demanded excellence, raising the bar for the on-court product and helping push the Cardinals to three national championships and 10 Final Fours. It made college basketball matter in a way it doesn’t anywhere else in the country, with Louisville regularly the top-rated market for the NCAA Tournament.

Over the past 10 years, though, that bond was tested in previously unforeseeable ways.

An escort scandal cost the school the 2013 NCAA championship, making the Cardinals the first-ever Division I men’s basketball program to vacate a title. Two years after Katina Powell’s now-famous accusations first went public, Louisville was ensnared in the FBI’s probe into college basketball, leading to the firings of Pitino, its hall of fame coach, and athletic director Tom Jurich, who built what was a commuter school into a sports juggernaut that rose all the way up from Conference USA to the ACC in just nine years.

A road back to respectability and normalcy seemed possible when the Cardinals were able to hire Mack, one of the sport’s brightest young coaches who had just led Xavier to a Big East championship, to replace Pitino in 2018, but in what became a distressingly familiar theme, that hope eventually turned to despair.

Mack led a team picked 11th in the ACC in the preseason to the NCAA Tournament in his first season and guided Louisville to a 24-7 record, which included a brief stint as the No. 1 team in the country, in his second season. The day it was set to tip off at the ACC Tournament, the event was canceled. Hours later, the NCAA Tournament was called off, as well. A team that had the potential to make the Final Four and lift the Cardinals out of the wreckage of the previous five years instead became a hypothetical that haunted the program in the years that immediately followed. Where might Louisville have been if a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic didn’t suddenly shut the world down?

From there, Mack’s once-promising tenure spiraled.

The Cardinals’ 2020-21 season was frequently interrupted by COVID-19, with eight of their 28 scheduled games canceled due to positive tests, all while their head coach wasn’t taking at least some of the precautions necessary for his team to play. That lack of games ultimately hurt them – after losing six of their final 10 contests, they were one of the first teams left out of the 2021 NCAA Tournament.

The following offseason, university leadership, perhaps overreacting to the tournament snub, forced Mack to make changes to his staff, which led to the ouster of Luke Murray and Dino Gaudio. Gaudio in particular didn’t handle his firing well, demanding to be paid for the next year and a half or else he’d expose (admittedly minor) NCAA rules violations. Mack secretly recorded the conversation, handed it over to school administrators and Gaudio was hit with one year probation for one count of interstate communication with the intent to extort. The ordeal was more embarrassing than scandalous, but it was another hit to a deteriorating marriage.

In Jan. 2022, with a dysfunctional 11-9 team and a frayed relationship with the university, Mack and Louisville mutually parted ways.

For whatever missteps Mack had over the course of his tenure, what followed next was worse – to put it mildly.

Looking to unite a fractured fan base and dip into the program’s glory days, Louisville turned to Kenny Payne, a freshman reserve on the Cardinals’ 1986 national championship team and a longtime assistant in college and the NBA, most notably with John Calipari at archrival Kentucky.

It didn’t quite work out as hoped. It wasn’t just that Payne failed; by hiring a first-time head coach to one of the sport’s most coveted, high-pressure jobs, there was always a chance that was going to happen. It was the extent to which he failed and the way he went about it.

A program that had 18 consecutive 20-win seasons from 2002-20 finished suffered 52 losses across two seasons, 33 of which came by double digits. Under Payne’s watch, the Cardinals had more losses by at least 20 points (14) than wins (12). Its 4-28 record in 2022-23 gave Louisville their fewest wins in a season since 1940-41. His second season was only so much better, with an 8-24 record and another last-place finish in the ACC. Over those 64 inglorious games, Louisville lost to the likes of Bellarmine, Wright State, Appalachian State, Chattanooga (by 10), Arkansas State (by 12) and Lipscomb. It was stunned in exhibitions by Lenoir-Rhyne and Kentucky Wesleyan, both Division II programs. He finished his tenure with a 5-37 record in ACC play.

Payne’s teams often appeared listless and inept, much like how NBA players in “Space Jam” looked after their talents were zapped from them by the film’s villainous aliens. Payne’s recruiting prowess from his days at Kentucky never really came to fruition at Louisville and even if it did, there was precious little evidence he could do anything to shape that talent into a cohesive, winning unit. Just a few weeks into his first season, Payne’s remark from his introductory press conference that he was going to need help from everybody suddenly seemed less like a rallying cry and more like a genuine plea from a man who knew he was in over his head.

For a former player who had been at the school for some of its greatest achievements, Payne displayed a galling lack of understanding of the importance of the program he was overseeing – or, at the very least, didn’t have the self-awareness to make it at least seem like he cared.

He regularly smiled and laughed with opposing coaches who had just handily beaten his team, including after the 10-point exhibition loss in 2022 to a Lenoir-Rhyne team that would go 6-12 in its Division II conference that season. He lamented how he was never going to have the most talented team – and chose to do so after losing to Kentucky Wesleyan in an exhibition. He said that Indiana coach Mike Woodson “tricked” him by switching to a 2-3 zone in the middle of a loss to the Hoosiers. When he was asked after a loss to Kentucky in 2023 about using Louisville’s archrival as a measuring stick for his program, he asked the reporter incredulously about all the all-Americans Kentucky had, as if his own program, with 21 all-Americans in its history, were fundamentally incapable of having the same studs on its roster.

“It was worse than I ever thought it could be,” Rutherford said. “If you had told me 10 years ago ‘Imagine a worst-case scenario for Louisville men’s basketball,’ I would not have come close to describing the way that it actually got. The on-the-court stuff…there are so many built-in advantages at this place and there’s such a large support system that you almost have to work to win only four games in a season or only 12 games in two seasons.”

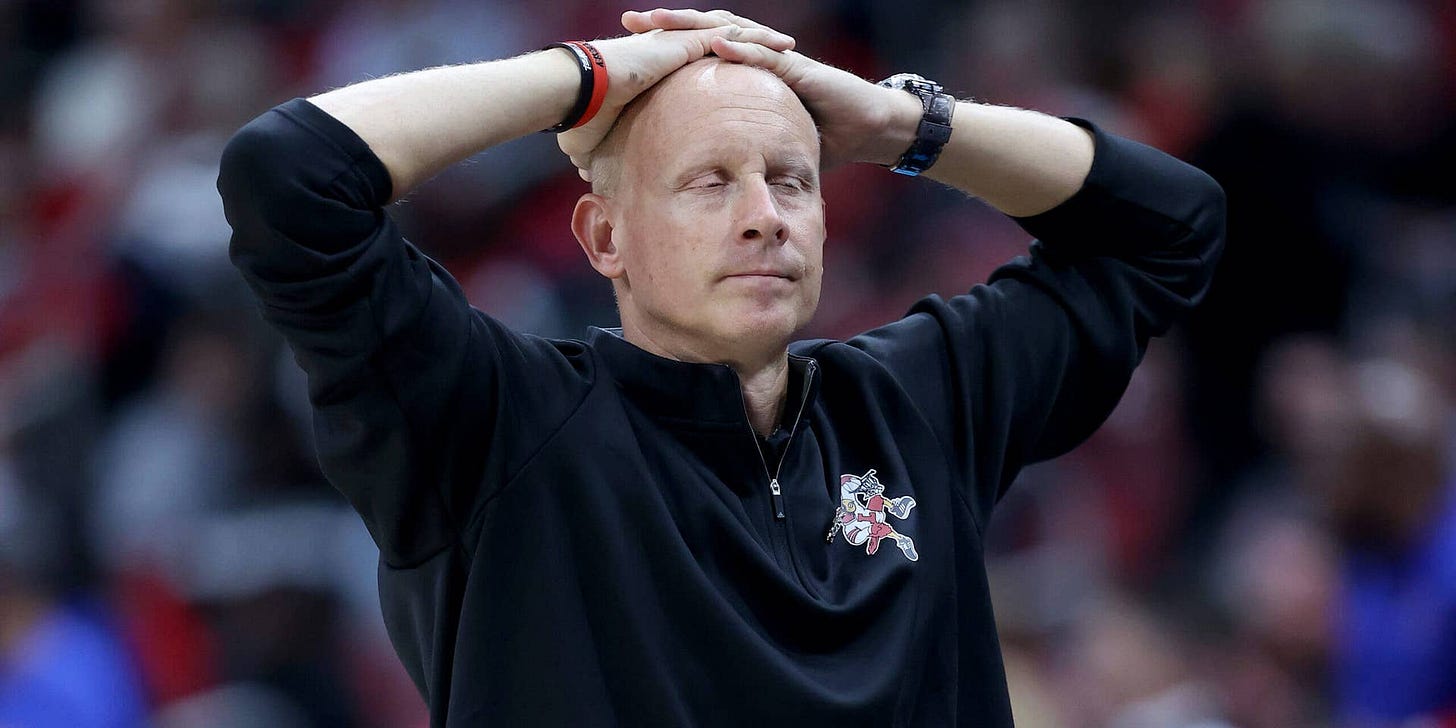

Payne’s ill-fated, short-lived stint at his alma mater ended in fittingly clumsy fashion. After a loss to NC State in the first round of the ACC Tournament, Payne chided fans in his post-game press conference for what he believed was a lack of patience, likening their disapproval to people jumping off the Titanic – a ship that passengers were famously wise to flee.

The next day, Payne was fired, with athletic director Josh Heird noting in a statement that “a change is needed.”

Pat Kelsey: Louisville’s unlikely savior

The obvious decision to get rid of Payne didn’t come with a clearly defined next step. Louisville had no shortage of options for its next coach – all of whom would have been an improvement – but it needed to find the right one, someone who would not only win, but who could build the Cardinals back into a championship contender.

The road to get there wasn’t always easy to navigate. Heird first unsuccessfully tried to lure over Scott Drew from Baylor. The search then turned its sights on Florida Atlantic’s Dusty May before he instead chose to go to Michigan. Other potential candidates like Indiana State’s Josh Schertz coached teams from one-bid leagues that had failed to win their conference tournaments.

A search that dragged on for 15 days ended on March 28, when Kelsey, most recently the coach at College of Charleston, was revealed as Heird’s choice.

Kelsey had racked up an impressive record over his 12 seasons as a head coach, going 261-122 at Charleston and Winthrop and making the NCAA Tournament four times. He had been a perpetual bridesmaid, too, someone whose name routinely came up for bigger jobs only for another coach to eventually end up with the gig, including twice at his alma mater, Xavier.

The reaction to his arrival was mixed. Kelsey’s infectious energy came through in an introductory press conference in which he hit on all the right notes, including the time-honored “I wasn’t my wife’s first choice, either” joke. Doubt remained, though. Was someone coming directly from the Coastal Athletic Association equipped to not only take over one of the sport’s biggest jobs, but rebuild it from the depths to which it had plummeted?

The challenges awaiting Kelsey went beyond the court.

Even by the end of Pitino’s wildly successful tenure, Louisville fans were fatigued by a seemingly endless series of scandals and NCAA investigations. Mack’s disappointing run shook whatever confidence they had that their program could recover quickly enough from the end of Pitino’s reign. Payne’s disastrous two-year stay then sunk the Cardinals to a once unfathomable nadir.

A fan base that once had justifiable expectations of conference championships and Final Fours had become accustomed to expecting – and often receiving – the worst. Colloquially, it became known as KPTSD, a nod to Payne’s initials.

“I kept giving the same message where I was like ‘Whatever you’ve got to do to get through this, do it,’” Rutherford said. “If it’s watching the games and feeling sad when they lose, do that. If it’s checking out completely, do that. If it’s watching the games and getting angry or making fun of what’s happening, do that. Just find a way to get through this and we’ll all gather back up when things are good. I can’t tell you the number of people in my life that were die-hard UofL fans for the entirety of their existence who just didn’t know when we were playing the last couple of years…There was a level of hurt that you can’t really put into words around here. Everyone handles pain differently. For a lot of people, it was just disconnecting completely. For other people, it was ‘I can’t disconnect completely. I’ve got to feel that pain. It’s going to make the joy whenever this gets back to being what it’s supposed to be feel that much better.’ It was tough on everybody. I think that everyone handled it in their own different way. You’re never prepared for that.”

As horrific as Payne’s two seasons were, some of the city’s scars predated him.

The crowds that once filled the opulent KFC Yum! Center had already started to thin out even during relatively successful stretches, with average attendance falling from 20,846 in Pitino’s final season to 16,658 during that fateful 2019-20 season three years later. COVID, as it did with everything else in American life, had a lingering impact. Louisville became one of the focal points of the 2020 racial justice protests after local resident Breonna Taylor was shot and killed by police officers, opening up old wounds and long-unaddressed problems in a highly segregated city.

It wasn’t on one person, much less a basketball coach, to cure everything that ailed a city, but the Cardinals, the preeminent source of civic pride, getting close to what they once were would be a hell of a start.

To do that, Kelsey had to get to work – and quickly.

Whether their decisions or his own, he didn’t return a single scholarship player from the previous season. To fill those spots, he turned to the transfer portal, where he could acquire experienced pieces to accelerate the rebuild, a task made easier by a sizable NIL warchest. Sharpshooter Reyne Smith and alluring-but-raw big man James Scott followed him from Charleston. Reigning Sun Belt player of the year Terrence Edwards came over from James Madison. J’Vonne Hadley – a hard-nosed, do-everything forward from Colorado – signed on. Pryor, after a breakout season at South Florida, brought some much needed size. In his most consequential addition, Kelsey secured a commitment from point guard Chucky Hepburn, a three-year starter at Wisconsin who’s one of the best on-ball defenders in the country.

For whatever hope the roster provided, there were some early hiccups that seemed to justify whatever skepticism there was entering the season.

Louisville was throttled by 22 by Tennessee in its second game of the season. Later that month, Pryor tore his ACL and it was announced that Washington transfer Koren Johnson, the reigning Pac-12 sixth man of the year, would miss the season after undergoing shoulder surgery. A suddenly short-handed squad was thumped by another SEC team, Ole Miss, and escaped with narrow wins against UTEP and Eastern Kentucky.

By the time the new year rolled around, though, those doubts about Kelsey and his first team at the school began to fade.

They went undefeated in a crucial four-game stretch in early January, beating North Carolina, picking up its first road win against Virginia since 1990, knocking off Clemson by double digits and earning a road win against what was then a fringe top-25 Pitt team. Momentum only grew from there. Since a Dec. 14 loss to Kentucky, Louisville is 17-1, with a loss at Georgia Tech the only blemish on the resume. Of its 17 wins during that run, 13 have come by at least 10 points.

Kelsey has done more than just win.

His team plays an up-tempo, entertaining and, perhaps most importantly, modern style predicated around 3s and shots at the rim. A roster that was assembled in only a couple of months has seamlessly coalesced, showing either a good eye for how pieces fit or a deft hand to make all those disparate parts come together (or both). The Cardinals have managed to do all of this without two of their eight best players. Kelsey’s after-timeout and baseline-out-of-bounds plays reliably produce a bucket or, at the very least, a quality look. His outgoing, engaging personality has helped connect with a fan base that had grown accustomed to coaches who were either uncomfortable or unwilling to embrace everything that came with the role.

In many ways, Kelsey, who grew up about 100 miles away in Cincinnati, has been what Payne was sold as – a basketball psycho who gets Louisville, its fans and the job’s quirks on a granular level and in a way that few others do.

“There’s just a general sense of this is back to the way it’s supposed to be,” Rutherford said. “This is kind of what we do.”

How Louisville is reconnecting with the Cards

While getting back to the NCAA Tournament is a laudable accomplishment, what this Louisville team has managed to do over the past four months is something that could outlast whatever happens this March.

This squad and the coach that put it together have repaired an all-important bond between a program and its city.

As the Cardinals languished on the court and away from it, there was a fear not only that some one-time diehards wouldn’t come back, but that a younger swath of fans wouldn’t have as much of a reason to forge the same emotional connection to the program that their parents and older siblings did. In that sense, Kelsey inherited a ticking clock. If he didn’t reverse the Cardinals’ fortunes quickly enough, Louisville risked losing an entire generation of fans.

This season, those existential worries have started to dissipate. A city that had grown numb to its team has started to fall back in love with it.

The text line to Rutherford’s radio show has served as a constant reminder of it, with stories flooding in from fans about how this season has changed their relationship to the program. A father had talked to his middle-school-aged son about a move he did in transition during one of his games that resembled a Euro step, only for his son to say he was mimicking a maneuver he regularly sees Edwards employ. More than a handful of people who are expecting a child have said they had decided on naming it Reyne. Others who have gotten into long-term relationships since Louisville was last nationally relevant have noted how they’ve startled their significant other with how much they care about the Cardinals, revealing a side to them that hadn’t previously been apparent.

Then there was the story of a teacher who noticed one of his students – a typically shy and reticent kid – come into class rocking an afro that was dyed blonde in the front, much like the hairdo Hepburn sports. During a break one day in class, he approached his student, brought up Hepburn and Louisville basketball and the child’s face lit up in a way he had never seen before.

“Stuff like that, not to get too over the top, but when people talk about ‘Oh, it’s just a game’...around here, it’s more than just a game,” Rutherford said. “The overall welfare of the entire city is better when Louisville basketball is giving us something positive to hang on to. When you hear stories like that, it just works to confirm that.”

The jubilance of this season is fleeting.

There will be a time in the not-so-distant future, maybe even as soon as next year, when a 23-6 record in early March is an expectation. It won’t merely be enough to make the tournament, but to advance deep into it. If Kelsey doesn’t offer ample evidence he can make a Final Four or win a national championship, he’ll only hold on to his position for so long, no matter how much he exceeded expectations in his first season.

There will be time to worry about the future, one that appears bright with a capable and charismatic young coach, several key returning players and a 2025 recruiting class that features five-star guard Mikel Brown, one of the highest-rated prospects in the program’s illustrious history.

For many in Louisville, though, that time hasn’t come, at least not yet. The present is too beautiful to look away from.

(Photos: Imagn Images, Getty Images, WAVE News, WDRB, Louisville Courier-Journal)