Lou Carnesecca was one of one

The longtime St. John's men's basketball coach, who died last weekend, was a character who won in a way few have ever been able to

There’s a memorable line near the end of “Requiem for the Big East,” ESPN’s 2014 documentary on the titular conference, in which the legendary scribe Charlie Pierce lamented the ways in which money contributed to the decline of the league and college basketball as a whole.

"They ran out all the poets and brought in all the salesmen,” he said.

One of those poets came in an unexpected form, a 5-foot-6 man named Luigi with a thick New York accent and an array of garish sweaters.

Despite his diminutive stature, Lou Carnesecca didn’t fit neatly into a box. Sadly, the past tense there isn’t a sign of him losing that trait, but the world losing him.

Carnesecca, the longtime St. John’s men’s basketball coach who most famously led the Red Storm (then the Redmen) to the 1985 Final Four, died last Saturday at the age of 99, only five weeks shy of what would have been his 100th birthday.

The way Pierce spoke of Carnesecca and other Big East coaches of that era wasn’t the result of hyperbolic sappiness. Carnesecca was truly a character, a figure who not only turned St. John’s into a national power in a way it hasn’t come particularly close to being since, but someone who did so in his own, irreplicable way. He was a pint-sized man with a gregarious, charming and magnetic personality, but those qualities often shielded aspects of him that were decidedly more human – namely, a mouth and vocabulary that rivaled even the best and most vulgar of his peers.

Mike Tranghese, the former Big East commissioner, once called him "our soul and our conscience" and "one of the giants of the game." To those who coached alongside or against him, he was simply “Looie.”

“Looie? Please, he’d start the game with a, ‘Bless you, my son,’ and then add a bunch of words I won’t repeat,’’ former Maryland coach Gary Williams, who coached against him in the Big East while at Boston College, said to The Athletic. “He had a mouth on him. He just made sure everyone knew he went to Mass in the morning.”

Carnesecca was a man who couldn’t be so easily summed up by a single, unifying theme in his life. He was simply too varied and too interesting.

In honor of his life and career, let’s take a look at some of the more fascinating aspects of a rich existence:

He had a quintessentially American story

Born in 1925, Carnesecca was the son of Italian immigrants who lived in Manhattan – East Harlem, more specifically – above the grocery store and deli owned by his father.

It didn’t take long for him to develop an interest in sports, rooting for the Yankees and fellow Italian-Americans like Joe DiMaggio and Tony Lazzeri while also (obviously) taking a liking to basketball, the quintessential city game. He eventually came to see those passions as a potential career and wanted to get into coaching. There was just one problem – his parents, particularly his dad, were having none of it, instead insisting that he study to become a doctor.

Carnesecca recounted the conversation in an interview with the Big East during the league’s 40th anniversary celebration.

“Pop, I don’t want to be a doctor.”

“What do you mean you don’t want to be a doctor? What do you want to do?”

“Coach.”

“Coach? What’s that?”

Then came the dagger.

“He looked at my mom and said ‘Look what you raised. He’s going to disgrace the family,’” Carnesecca said.

He ultimately tried to fulfill his father’s wishes, enrolling in a pre-med program at Fordham, but transferred to St. John’s after just one year.

He certainly couldn’t be accused of laziness. Once he was of legal military age, he became a member of the U.S. Coast Guard during World War II. After enrolling at the school with which he would become synonymous, Carnesecca became an athletic standout, but on the baseball diamond, not the basketball court. He was even a member of a St. John’s team that made the College World Series in 1949.

In short, he was anything but a disgrace. And that was before he made his way into the profession that would make him famous.

He was a success in a way few have been

There’s a beautifully outdated quality to the way Carnesecca’s coaching career unfolded.

After graduating from St. John’s, he landed a job at his high school alma mater, St. Ann’s (now Archbishop Molloy) in Queens. He lost 11 games in his first season, but quickly found his footing, losing just 23 games combined over the next six seasons. By 1958, and in what would be his eighth and final season in the high school ranks, the team he led finished a perfect 32-0.

The thirty-something winning all those games at one Queens school attracted the attention of another academic institution in the borough.

Following that undefeated season, Carnesecca was brought back to St. John’s as an assistant coach by Joe Lapchick. In 1965, mandatory university rules of the era forced Lapchick to retire when he turned 65 years old and, having gotten the opportunity to see his top assistant at work, St. John’s leadership handed the keys to the program over to Carnesecca. By his second season, he led the Johnnies to a 23-5 mark and a spot in the Sweet 16.

The temptation of coaching pro basketball eventually was too much for Carnesecca to dismiss and after his fifth season at St. John’s, he left to become the coach of the ABA’s New York Nets. He excelled there, too, guiding the Nets to the ABA Finals in 1972, but after star player Rick Barry left for the NBA’s Golden State Warriors, the team’s fortunes waned.

In a bit of kismet, Carnesecca’s old job opened when his successor, Frank Mulzoff, stepped down after contract negotiations hit a snag. Were it not for that, Carnesecca later joked, he would have been back in his father’s deli cutting salami (while probably getting an earful about not being a doctor.)

Trying to recreate something that once was is overwhelmingly a fool’s errand in college sports, with far more cautionary tales than success stories. A coach can return to the site of past glory, but it rarely goes as well as it did the first time around, if it even goes well at all (Bill Snyder at Kansas State is a notable exception in college football.)

For Carnesecca and St. John’s, though, it worked. If anything, he and his teams were even better.

Over his 24 seasons at his alma mater, he went 526-200, with the bulk of that work coming in his second stint at the university. After he returned in 1973, Carnesecca went 422-165. From 1975-92, his teams made the NCAA Tournament in every year but two – and even in those two seasons, they went 17-11 and 20-13. In eight of those tournament appearances, there were a No. 6 seed or better.

He awoke a sleeping giant

The conversation around the St. John’s basketball program, even for those who love and follow the sport, can often be misguided and overly simplistic.

If they can just get the best players in New York City to stay home, the refrain goes, they can be a powerhouse.

I’ve gone into detail in this newsletter before about the fallacy of the sleeping giant, using the men’s basketball programs at Georgia Tech and DePaul as examples, but during Carnesecca’s reign at St. John’s, that otherwise fanciful idea of building a winner by constructing a metaphorical fence around a talent-rich area actually worked.

Carnesecca prioritized New York City in a way many of his successors aimed to, but largely failed to. His roots in the city gave him connections all across the five boroughs. If you think about it, he never really left. He was recruiting that area not only because of some of the prospects it had to offer, but because it was all he really knew.

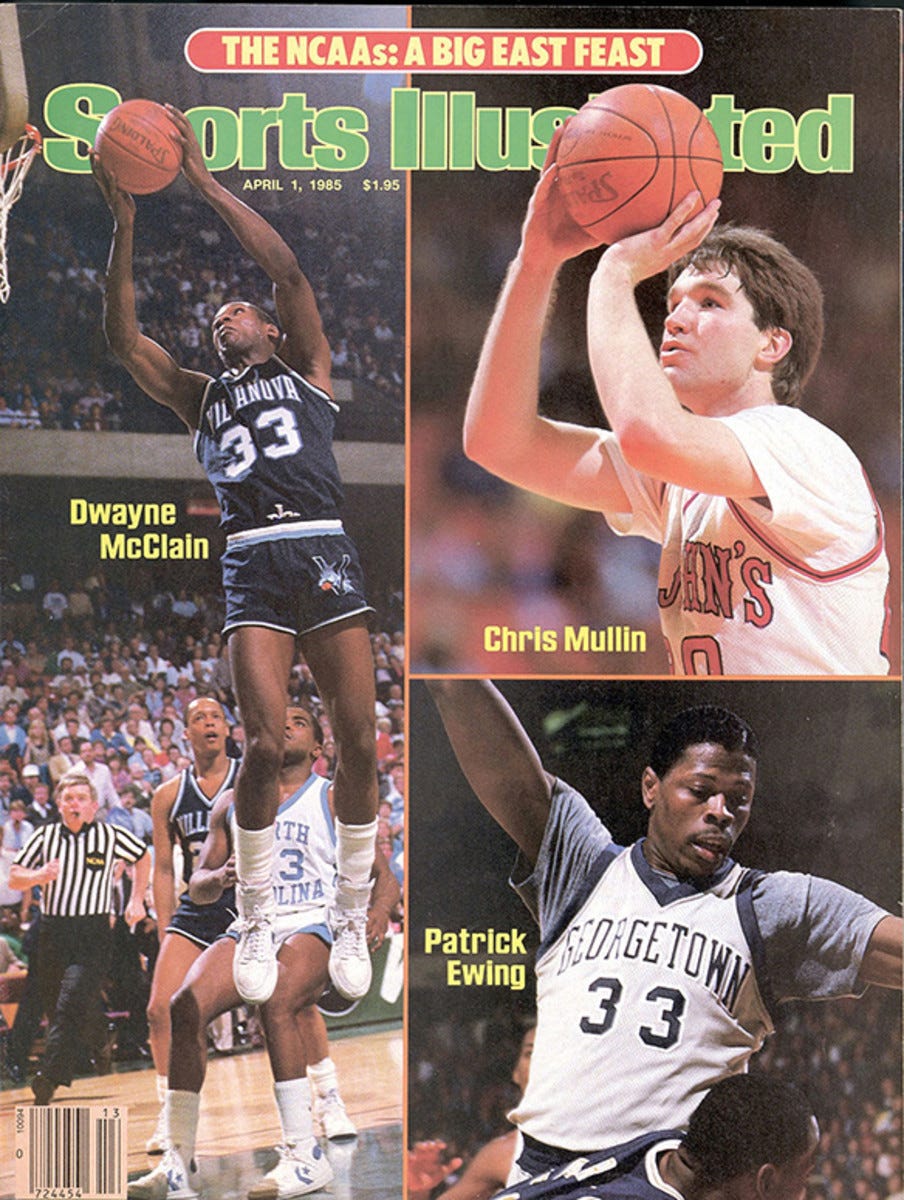

Many of the Johnnies’ best players were New York kids. Mark Jackson was from Brooklyn. Walter Berry came from Benjamin Franklin High School in Carnesecca’s old stomping grounds of East Harlem. Big man Bill Wennington, while born in Montreal, came up through Long Island. Then, of course, there was Carnesecca’s most prodigious pupil – the Brooklyn-born-and-bred Chris Mullin, who was recruited by damn near every school in the country, but decided to stay home and suit up for a program that was playing its games in Madison Square Garden and capturing the imagination of a basketball-crazed city that was eager to embrace one of its own teams after decades of being in the proverbial wilderness following the wreckage of the CCNY point-shaving scandal in the 1950s.

Carnesecca’s work was easier said than done, especially during a time in which many top New York basketball players, going back to Power Memorial’s Lew Alcindor signing with UCLA, heading to colleges in the west and south.

Carnesecca was well aware of what he was able to accomplish. He once said the furthest he went for a player was New Jersey, something that he was maybe only slightly exaggerating about. When asked once why he never seemed to venture far beyond New York for talent, he pulled out a subway token.

“That’s my recruiting budget,” he said.

It was all he really needed.

St. John’s never made it to college basketball’s mountaintop, climaxing in 1985 with a Mullin-led squad that fell to Big East rival Georgetown in the Final Four in a year in which the league accounted for three of the four national semifinalists, but he did the next best thing – putting forth a remarkably steady winner.

Of his 24 seasons as a head coach, his teams won at least 20 games 18 times. The Johnnies made some kind of postseason in each of those 24 seasons and, perhaps most impressively, never finished a season with a losing record.

"I never scored a basket," he said at his induction into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 1992. "The players did everything. Without players, you can't have a game."

While the modesty’s admirable, Carnesecca was able to accomplish what few at St. John’s ever have. The program had enjoyed periods of high-level national success prior to his arrival – including making the NCAA title game in 1952 under Frank McGuire before he left after the season for North Carolina – but never for as sustained of a stretch as Carnesecca maintained.

St. John’s has been trying to reach that bar Carnesecca set since his retirement in 1992, but has failed far more often than it has succeeded. The Red Storm went 69-72 combined in the five seasons after his departure. They’ve made the NCAA Tournament only three times since 2003. After Carnesecca had 18 20-win seasons in his 24 years at the helm, St. John’s has only reached the 20-win mark 10 times in the past 32 seasons.

*****

Death is inherently cruel, but something about Carnesecca’s death occurring on the final Saturday of the college football regular season seemed particularly unfair, with much of the American sporting public too firmly fixated on the race for the College Football Playoff to care about much of anything else.

Carnesecca was one of the interview subjects in the aforementioned ESPN documentary about the Big East. Shortly before Pierce delivered that literary banger of a line, Carnesecca was offering his own version of an autopsy, noting that from a financial and fan interest standpoint, college basketball simply can’t compete with its football counterpart.

He’s right, of course, but there was a certain sadness I felt listening to such a decorated figure sound so defeated.

But in the same way that Carnecessa’s achievements could never be negated by the television viewing preferences of millions of Americans, the timing of his death does nothing to dampen what he did in the nearly full century preceding it.

In that same interview for the Big East’s 40th anniversary, Carnesecca insisted that he not be referred to as a legend. His reasoning was sound enough.

“Legends are dead,” he said. “I am what I am. What you see is what you get.”

If there’s one good thing to come from an otherwise somber development, it’s that he can now, by his own definition, be rightfully revered as the legend that he is.

(Photos: Associated Press, Getty Images, Sports Illustrated)

Craig - I know Louie was Italian, but he always seemed like a leprechaun to me. So endearing. That era of the Big East will always be special to me.

I fell behind in my reading because of a house project. Unfortunately, I now have time to get caught up on my reading. I lost my husband unexpectedly 5 weeks ago. He had just turned 60 and appeared to be in good health when he collapsed at a dinner for a charity golf outing. (It was the Willie Stargell Foundation and he was with 3 guys he knew from Fantasy Camp.)

I'm still trying to wrap my head around it.

Aileen