Long before the Nova Knicks, Rick Pitino tried to recreate his Kentucky empire with the Celtics

Stockpiling an NBA team with players from a successful college outfit isn't a totally new concept. But it's never worked this well

When Mikal Bridges was traded across the East River from the Brooklyn Nets to the New York Knicks in a blockbuster deal last month, the move drew more than a few knowing laughs.

For the past two years, the Knicks have been stockpiling former Villanova standouts. It began in 2022, when Jalen Brunson signed a four-year, $104 million deal with the club that almost instantly looked like a bargain for a player who has blossomed into an all-star and franchise pillar. About midway through Brunson’s first season in New York, they traded for Josh Hart, his teammate for two seasons at Villanova. The following offseason, they signed Donte DiVincenzo, a member of two national title teams with the Wildcats.

Now, that college reunion has another member (last season’s Knicks had another former Villanova hooper, Ryan Arcidiacono, but he logged only 45 total minutes and didn’t score a point).

The price to acquire Bridges was immense – a haul that included five first-round picks – particularly for a player who has never so much as made an all-star game.

By bringing on Bridges, though, the Knicks leaned even further into what has been a successful identity. With Brunson, DiVincenzo and Hart serving as three of the team’s regular starters, New York had its best season in a decade, winning 50 games and earning the No. 2 seed in the eastern conference for the NBA playoffs. With Bridges now aboard, the Knicks stand as perhaps the biggest threat to the reigning NBA champion Boston Celtics in the east.

Even if it’s not done intentionally, there’s a logic to the plan. Under Jay Wright, Villanova was college basketball’s most successful program of the 2010s, winning seven Big East regular season championships from 2014-21 and a pair of NCAA titles. Trying to replicate that culture, familiarity and togetherness at the professional level isn’t the worst idea and based on the results, it’s been quite fruitful. A team dubbed the “Nova Knicks” has been an unquestionable success.

But trying to recreate the magic of a college basketball champion in the NBA doesn’t always work so well. Just ask Rick Pitino.

How Boston became Kentucky North

By virtually any measurement, the 1995-96 Kentucky team is one of the greatest college basketball teams of all-time, men’s or women’s.

That season, the Wildcats were a machine, posting a 34-2 record and a 16-0 mark in SEC play. Their only two losses came against teams that would go on to make the Final Four, UMass and Mississippi State. All but two of their 28 victories heading into the NCAA Tournament that year came by double digits, 16 of which came by at least 20 points. They won by a combined 113 points on their way to the Final Four and once there, didn’t win either of their final two games by fewer than seven.

When discussing the team known as “The Untouchables,” one statistic stands out above all others – nine of its 13 scholarship players went on to the NBA, with only one player who averaged more than four points per game failing to do so.

The squad represented the crowning achievement of Pitino’s tenure, one in which he transformed a program decimated by scandal into a juggernaut that was the envy of the sport by the time he left in 1997 to become the head coach and president of the Boston Celtics.

Once he got to Boston and was tasked with not just coaching a team but assembling one, his roster began to take on a familiar shape. A quarter-century before the Nova Knicks were born, there were the Kentucky Celtics.

Those building efforts began unintentionally and even before Pitino got there.

In 1996, the Celtics took Antoine Walker, perhaps the biggest star from the Wildcats’ title team, with the No. 6 overall pick in the NBA Draft. By the time Pitino got there, though, it was clear he prioritized his former forward, who made the NBA all-rookie team in 1997 after averaging 17.5 points and nine rebounds per game. Shortly after being hired, Pitino said there was nobody the Celtics would trade Walker for outside of Michael Jordan (considering Jordan was 34 years old and a year away from retiring, it was maybe the first warning that Pitino’s front-office acumen wasn’t exactly top-notch).

In the months that followed, that Kentucky-centric process accelerated.

In Pitino’s first NBA Draft at the helm, the Celtics had two of the top six picks, one of which, unfortunately for them, was not the No. 1 overall selection, where they would have nabbed Tim Duncan. Given the way the ping pong balls bounced, Boston settled on its backcourt of the future. At No. 3, it nabbed Colorado guard Chauncey Billups, a future all-star and NBA Finals MVP (though obviously not with the Celtics). Three picks later, it took another guard, Ron Mercer, from…Kentucky.

Mercer was recruited by Pitino and morphed into a star shooting guard under his tutelage, earning consensus first-team all-American honors as a sophomore in 1997. Reuniting with his college coach in the NBA wasn’t a certainty, though.

While Mercer was an excellent outside shooter in college, there were concerns about his ability to consistently get his shot off at the next level. There were rumors that Boston wouldn’t take him because there was friction between him and Walker in college, chatter that both players and Pitino shot down. There was also another scoring guard, high-schooler Tracy McGrady, that the Celtics were reportedly enamored with, though the future all-NBA player revealed years later that he sandbagged his interview with Boston because he didn’t want to play for Pitino. The Celtics also worked up to draft day on a trade that would have sent Scottie Pippen and Luc Longley to Boston for the Nos. 3 and 6 picks, as well as Boston’s first-round pick in 1998, but the deal fell through.

“I’ve been with Coach for two years,” Mercer said after he was selected in 1997. “I really didn’t think he would pass on me.”

Having two former Kentucky players on a roster being pieced together by a former Kentucky coach was notable, but it could easily be written off as a coincidence. Walker was there before Pitino’s hiring and Mercer was a projected top-10 pick who was taken in that range.

What happened next was when things began to feel a bit more intentional.

In Oct. 1997, just weeks before the start of Pitino’s first season, the Celtics traded Chris Mills – who Boston had signed just two months earlier to a seven-year, $34 million deal – to the Knicks for four players, including second-year forward Walter McCarty, another one of the stars from Kentucky’s 1996 national championship squad.

(Mills, interestingly, allegedly received improper benefits from a Kentucky booster while on the Wildcats in the late 1980s, a scandal that gutted the Kentucky program and created a coaching vacancy that would ultimately be filled by Pitino.)

The odd timing of it aside, the trade gave another productive piece to an aging New York team in win-now mode while giving the young Celtics some potentially promising pieces around which they could build. Among that group of new acquisitions, one stood out.

"We've had our eye on Walter McCarty for some time," Pitino said at the time of the trade.

McCarty had done little to nothing as a rookie for the Knicks, averaging just 1.8 points and 0.7 rebounds in 5.5 minutes per game after being selected with the No. 19 overall pick in the 1996 NBA Draft.

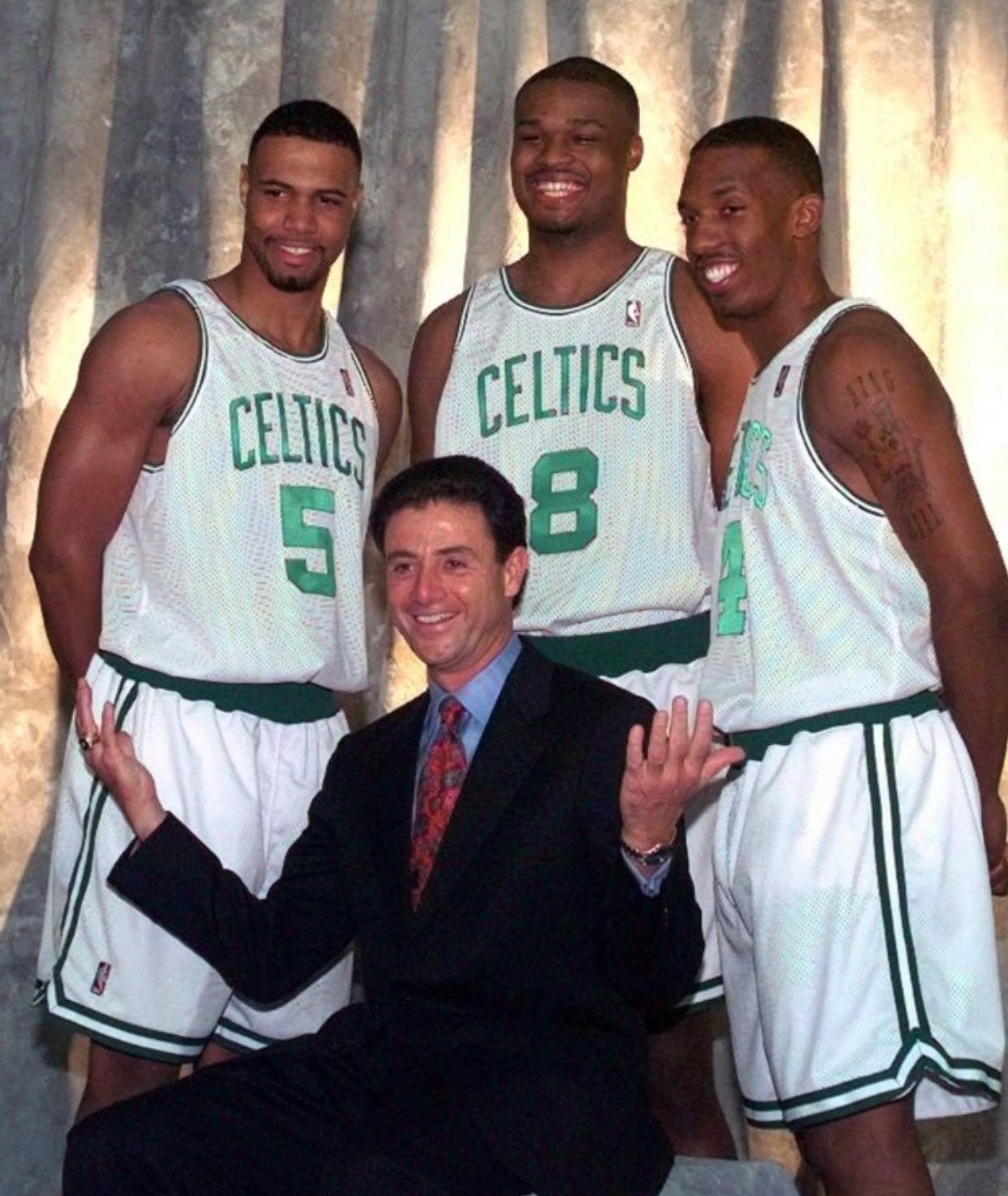

His arrival in Boston meant that one quarter of Pitino’s first Celtics team played for him in college. Understandably, others began to take notice.

In the days after the Mills trade, Peter May of the Boston Globe wrote about the move and what, specifically, the addition of McCarty might mean:

Rick Pitino went out on a limb yesterday and said he was not interested in signing Anthony Epps.

This has to be a first: three guys from the same college team, an NCAA championship team at that, joining their college coach on the same pro team. Meet the new boss. Same as the old boss.

“I have a lot of loyalty and respect for the University of Kentucky, but I am not taking these players because they played for Kentucky,” Pitino said. “These players can play. I know their games. They happened to play for Kentucky. These are three guys who were the focus of a championship team.”

You can already hear the guffaws around the NBA. Who’s next, Epps? Or Mark Pope? Are the Celtics changing colors to blue and white? Will they play their home games in Lexington? Is the Vanderbilt game this week or next?

While skepticism was certainly merited, the series of moves could be easily justified. A coach who was preparing to implement a full-court pressing and trapping defense, a rarity at the NBA level, would need players who would not only be open to operating in such a system, but be familiar with some of its nuances. If you can snag such players from one of the most dominant teams in college basketball history, well, that’s all the better.

But would it work?

How’d Pitino’s experiment pan out?

Though it’s rightly remembered as a disaster, Pitino’s Celtics tenure began on an encouraging note.

In its first game of the 1997-98 season, Boston overcame a 20-point first-quarter deficit to defeat the two-time reigning NBA champion Bulls 92-85, with Jordan making just seven of his 23 shots.

The three Kentucky players, all of whom started, account for 51 of the team’s points, 31 of which came from Walker.

“I think this is the most special opening night I’ve ever had as a coach,” Pitino said after the game.

While they wouldn’t maintain a “beat the eventual NBA champions” type of pace, the Celtics proved to be a young, exciting outfit in their first season under Pitino. They finished 36-46, a 21-win improvement from the previous season.

The ex-Wildcats had a sizable say in that progress. They accounted for three of the Celtics’ top six scorers, with Walker finishing first at 22.4 points per game, along with a team-high 10.2 rebounds per game, and Mercer second at 15.3. Like Walker the year before, Mercer made the NBA all-rookie team. McCarty, for this part, averaged what would turn out to be a career-high 9.6 points and 4.4 rebounds per game.

(It should be noted, too, that Mercer and Billups were accused in 1997 of raping a woman while at Walker’s home. The two players settled with the alleged victim in 2000 for an undisclosed sum of money.)

The optimism that surrounded the Pitino Celtics was short-lived. The team stumbled during the lockout-shortened 1998-99 season, finishing 19-31. McCarty was limited to 32 games, only four of which he started, and Walker’s production slipped a bit, due at least in some part to the emergence of another young player who would soon become the face of the franchise – Paul Pierce. The idea that NBA players would press for 48 minutes in a physically grueling 82-game season backfired spectacularly.

Perhaps most notably, that Kentucky nucleus wouldn’t remain intact beyond that season.

After upping his scoring average to 17 points per game, Mercer was traded in Aug. 1999, about three months before his third NBA season, landing with the Denver Nuggets as part of a six-player deal.

The split was somewhat contentious. Pitino publicly said he wanted to hold on to Mercer, but that he “could not even come close to the numbers Ron Mercer wanted as a basketball player” with free agency looming for the guard after the 1999-2000 season. Mercer’s agent, Tevester Scott, saw it a bit differently, telling the Globe that “I can’t get into specifics, but they totally disrespected his ability as a basketball player with the money they offered him. There are guys on the bench who make more money than what they were offering.”

Locally, there was notable support on the side of Pitino and the Celtics in the ordeal. As the great Bob Ryan wrote in the Globe after Mercer was dealt:

What’s happening to the Celtics happens to every team. A kid like Mercer enters the NBA, does very nicely, and that’s all. He sets no records, evokes no memories of Michael Jordan, does not establish himself as a franchise player and, in fact, tails off a bit in Year 2 from his nice rookie season and then decides he is worth the maximum money available for his next contract.

In Mercer’s case, he was clearly the third-most important commodity on the team. Had he been realistic, he’d still be here.

Regardless of who was at fault, the experiment was over.

With Mercer gone, Pitino actually replenished the roster with another Kentucky player – signing undrafted free agent Wayne Turner, who he coached from 1995-97 – but the move was largely inconsequential, with Turner logging just 41 minutes across three games in Boston.

That 1997-98 season would prove to be the apex of Pitino’s ill-fated tenure with the Celtics. He went 35-47 in 1999-2000 and 34 games into his fourth season, and with Boston languishing at 12-22, Pitino resigned.

A little more than a year later, the Celtics, under former Pitino assistant Jim O’Brien, went 49-33 and made it all the way to the Eastern Conference finals, with Walker making the all-star game while finishing second on the team in scoring. Walker and McCarty would remain with the Celtics – the former as a No. 2 scoring option behind Pierce and the latter as a beloved, albeit not terribly productive role player – until they were dealt in separate trades during the 2004-05 season.

Of course, that ignominious two-year stretch of Celtics history has no bearing on what’s currently unfolding in New York. The Nova Knicks aren’t some sort of theoretical concept. They’ve been quite successful and with Bridges, and barring any significant injuries, that should only continue.

At the very least, it has worked better for the Knicks than it did for the man with whom they share Madison Square Garden.

(Photos: Getty Images, Allsport)