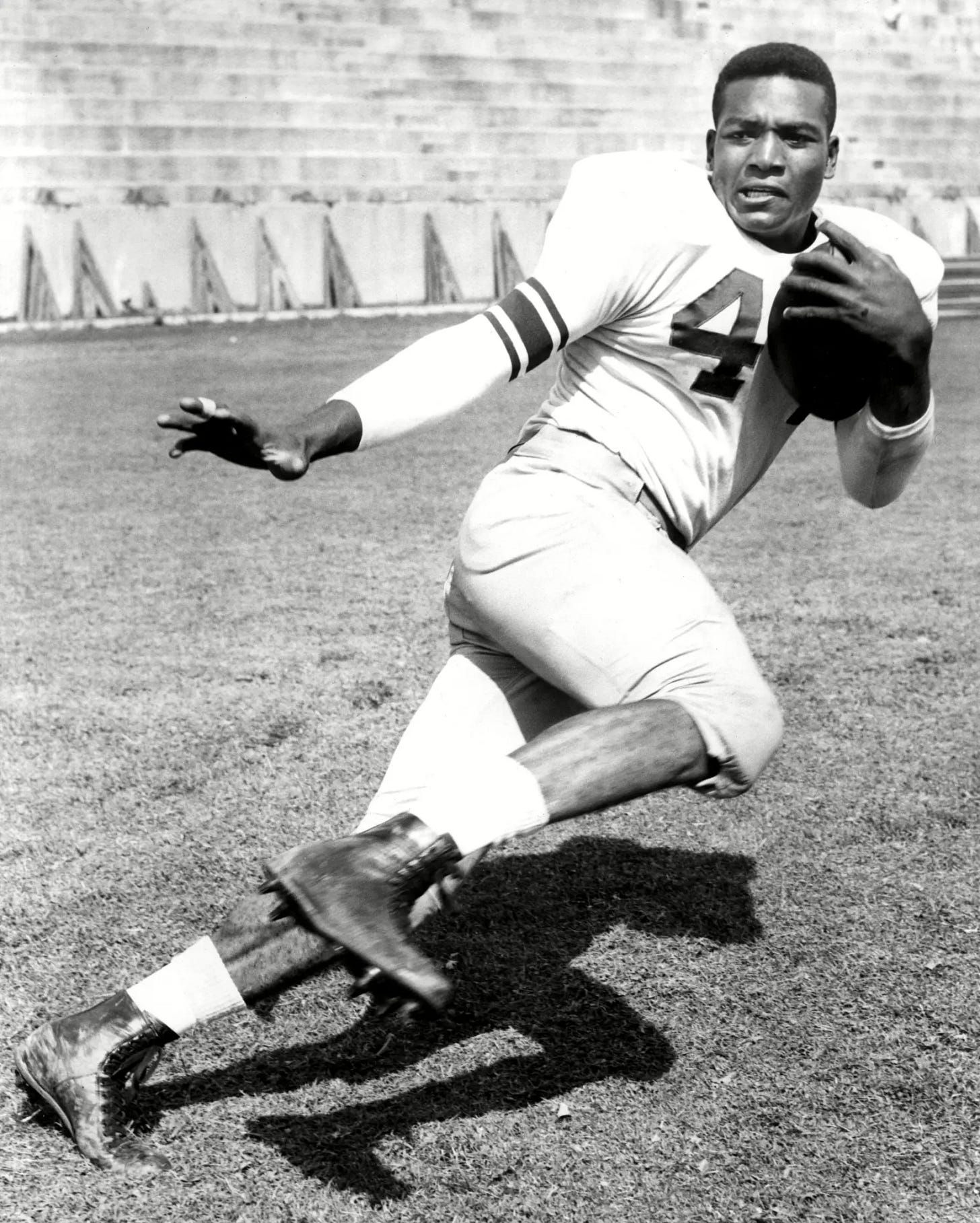

Jim Brown and the puzzling 1956 Heisman Trophy vote

Brown, who died last week, is regarded as one of the best college football players ever, if not the greatest. So how did he lose out on the sport's biggest prize to a quarterback from a 2-8 team?

Over the course of his life, which ended last Thursday at the age of 87, Jim Brown was many things.

Most notably, he’s one of the greatest football players to ever strap on a helmet, possessing a combination of strength, speed and athleticism that was unprecedented in his time and has been largely unmatched since. While many stars from his era have been forgotten or, worse, discredited, he’s still widely exalted, even by those who never saw him play.

Beyond his professional football career, he was a movie star, a towering figure in the fight for racial justice, a tireless advocate for ending gang violence and, according to a slew of allegations, a serial abuser of women. His life and actions never placed him comfortably in a single box, prompting many eulogizing him to describe him as “complicated.” As Howard Bryant, the phenomenal sports writer and author, succinctly said “Jim Brown is heroic, but he's no hero.”

The mythology surrounding Brown began in earnest in college, where he earned 10 varsity letters in four sports at Syracuse. As any obituary on him will note, he’s one of the greatest lacrosse players ever, a two-time all-American who was so good that the NCAA had to change its rules to force players to keep their sticks in constant motion while carrying the ball. As a sophomore, he averaged 15 points for the Orange’s basketball team, just 0.8 fewer than eventual all-American Vinnie Cohen. He excelled at track, as well, placing fifth in the decathlon at the 1954 National AAU meet despite not training for it.

Of course, it was football where he made his biggest and most memorable mark. Playing for a school that once refused to offer him a scholarship, Brown racked up 2,091 rushing yards, 26 touchdowns and eight interceptions over the course of his three years playing varsity football. In Jan. 2020, an ESPN-commissioned panel of 150 media members, college administrators, former coaches and former players voted Brown as the greatest player in college football history.

Yet, despite all of those accomplishments, Brown left Syracuse without the sport’s most prestigious and coveted award – the Heisman Trophy.

How, exactly, does that happen? It’s a simple question without a concise, straightforward answer.

In 1956, his final year of college football, Brown was a force of nature. His 986 rushing yards ranked him third among all college football players and his 13 rushing touchdowns were tied for the most nationally. The two players ahead of him in rushing yards both played one more game than him. He was not only productive, but efficient, averaging 6.2 yards per carry. With those individual triumphs came team success, as Syracuse finished that season 7-2 and a No. 8 ranking in the final Associated Press poll that season, the highest such finish in program history to that point.

It’s the kind of profile seemingly tailor-made for the Heisman – a prodigious talent who played a high-profile position in which he regularly touched the ball and who played an integral role on a winning team.

That Brown never hoisted the trophy is confounding enough. But when examining who won it that season, it becomes that much stranger.

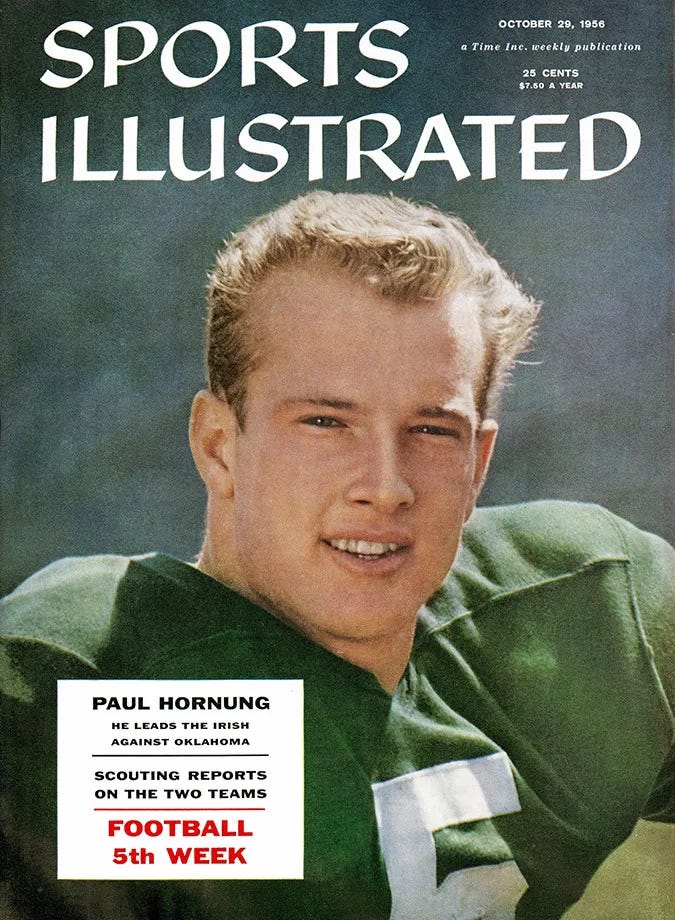

While not to the absurdly high level of Brown, Paul Hornung was a remarkably decorated football player, a four-time NFL champion, one-time NFL most valuable player and a Pro Football Hall of Fame member. What he was able to achieve on the field is largely beyond questioning and critique – except for one notable thing.

In 1956, it was Hornung, not Brown, who was voted as the Heisman winner, with the Notre Dame quarterback finishing at the top of one of the tightest races in the award’s 88-year history. At first glance, a future NFL star being crowned as college football’s top player doesn’t qualify as bizarre. But on his way to winning the award, Hornung compiled a resume unmatched among past Heisman winners – and not because of its strength.

That season, Hornung threw just three touchdowns to 13 interceptions, giving him only two more touchdowns than Brown despite throwing 107 more passes that season than the Syracuse star. His three touchdowns were the fewest ever for a Heisman-winning quarterback. Those underwhelming numbers weren’t merely a product of a different, bygone era. In 1956, 26 quarterbacks threw at least six touchdowns. Even his raw passing production, with 917 yards, ranked him behind 11 other players. He threw an interception once every 8.5 passes.

An award so thoroughly rooted in narrative – sometimes at the expense of more sound reasoning – could feasibly be given to a prominent player on a championship-caliber team, with voters opting to look past mediocre or outright poor stats to reward someone for their team’s success. But that season, Notre Dame finished just 2-8, still tied for the fewest wins and lowest win percentage in a season in program history. The Fighting Irish didn’t just lose games, but were regularly blown out, dropping four of those eight contests by at least 25 points.

Hornung spent a sizable chunk of the post-Heisman interviews not reveling in his achievement, but explaining just why his team struggled so mightily at a school with drastically higher expectations.

Hornung’s candidacy wasn’t devoid of merit. Even at a time when it wasn’t exceedingly rare to play multiple positions, he suited up at quarterback, halfback and kicker. While playing through injury, he led Notre Dame in punt return yards, kickoff returns yards, scoring, passing yards and rushing yards. He was a capable running threat, too, with 420 yards, 4.5 yards per carry and six touchdowns.

“Although apparently there is a concerted move on the West Coast to “stuff” the ballot box with the name of Jon Arnett from SC just to prove to dust farmers in the midwest that we, too, can kick up a voting storm if we try, I can’t conceivably see how any single college football player this season can compare with Hornung as an all-around performer,” Hank Hollingsworth wrote in the Long Beach Press-Telegram on Nov. 27, 1956. “Heck, the man passes, runs, converts, kicks off, blocks, calls signals, punts, makes half the tackles, drops kicks, and helps the groundskeeper after home games at South Bend.”

But even the most generous interpretation of Hornung’s season can’t negate who he beat for the award, beyond even Brown.

Tennessee running back Johnny Majors, the second-place finisher who later went on to a storied coaching career at his alma mater and Pitt, was a do-everything star like Hornung, playing tailback (549 yards, seven touchdowns), quarterback (552 yards, five touchdowns, three interceptions), kick returner, punt returner and safety. He also happened to do so on a Volunteers team that finished 10-1 and No. 2 in the country.

Then there were a pair of Oklahoma teammates, Tommy McDonald and Jerry Tubbs, who finished in third and fourth, respectively. McDonald, a Pro Football Hall of Famer himself, had a higher yards-per-carry average than even Brown (7.2) while adding 282 receiving yards and four touchdowns. Tubbs was another two-way standout, thriving as both a center and linebacker. The contributions from both helped guide the Sooners to an undefeated record and a national title.

Many newspaper articles at the time, particularly from southern outlets, regularly framed the Heisman race as a four-man battle, citing Brown, Majors, McDonald and Tubbs while omitting Hornung entirely. Hornung himself was even surprised upon receiving the news he had been declared the victor, telling the South Bend Tribune at the time that “I thought they were kidding me.”

Nearly 70 years later, though, it’s still Brown who stands as the most galling snub in a convoluted and controversial saga in the sport’s history.

Based purely on his on-field feats, Brown had a compelling and obvious claim for the honor. His final performance was his most persuasive piece of evidence yet, as he racked up 43 points by himself – six touchdowns and seven extra points – in a 61-7 win against Colgate in Nov. 1956. That mark stood as an NCAA record until 1990.

But any award, particularly one with as nebulously defined criteria as the Heisman, takes other factors into consideration. In the mid-1950s, some of those variables were puzzling, at best, and nefarious, at worst, and all of which was painfully outside of Brown’s control.

Part of it was tied to the grandiosity and lore of Notre Dame, which claimed five of the previous 14 Heisman winners after Hornung secured it. For many of his shortcomings in 1956, Hornung was the “Golden Boy”, occupying the highest-profile position in the sport while earning praise and glowing coverage that sometimes strayed past the lines of competition. While quoting him in Dec. 1956, the AP made sure to add the qualifier that Hornung was “a good-looking, 205-pound blond from Louisville.”

Visibility was also an issue for Brown. Syracuse didn’t play in a nationally televised game that season until the Cotton Bowl, which was played a month after Heisman votes were tabulated. The Orange were an ascendant program, but at that time, they weren’t a national brand that commanded attention beyond their corner of the country. It was a fact reflected in the Heisman Trophy voting, as Brown was the top vote-getter in the east, but didn’t finish higher than fifth in any of the four other regions.

Then, of course, there’s the unavoidable issue of race.

In 1956, a majority of college football programs hadn’t yet integrated. Even at Syracuse, hundreds of miles from the codified segregation of the Jim Crow South, Brown encountered racist mistreatment. According to Brown biographer Mike Freeman, Orange coaches were initially reluctant to allow Brown on the team unless he agreed not to date white women. Brown was only able to attend Syracuse initially because Ken Molloy, a former Orange athlete and university benefactor, paid for the running back’s first year of tuition.

The men tasked with awarding the Heisman at that time were exclusively white men, a number of whom, based on the time in which they lived, harbored racial animus. To that point, a Black man had never won the Heisman and in 1956, each of the four players who finished ahead of Brown in voting were white. It wouldn’t be until 1961 when another Syracuse running back, Ernie Davis, broke through and snagged the sport’s top prize, despite having worse stats than Brown in nearly every major category.

Interestingly, the only other region where Brown finished in the top five of the Heisman balloting was in the south. In the midwest, southwest and west, he was left off entirely, speaking to a broader, more pervasive problem that doesn’t have a convenient, tried-and-true scapegoat.

There was little outrage about Brown’s fifth-place finish, at least based on documented accounts from the time. Naturally, there were exceptions. Legendary journalist Dick Schaap was a loud and proud advocate of Brown, having not only watched him in person, but having played lacrosse against him when Schaap attended Cornell. Schaap voted for Brown and upon seeing the results, he was so disgusted that he withheld his Heisman vote and boycotted the proceeding for more than 20 years.

It wasn’t until the voting pool diversified, bigotry generally waned and Brown’s greatness became so obvious that more people joined Schaap.

“That the best player in the history of college football didn't win the Heisman Trophy says less about the player than it does about college football,” ESPN’s Ivan Maisel wrote in 2020 when introducing the top 150 players list. “Jim Brown of Syracuse finished fifth in the vote to select the most outstanding player of 1956. A significant portion of the electorate balked at voting for a black man. Coaches always maintain that the longer a game goes, the more that talent will reveal itself.”

Even without a stiff-arming statuette among his horde of trophies, Brown did just that.

Unreal. I had no idea that Brown never won the Heisman, never mind that the Heisman was awarded his senior year to the QB of a 2-8 team. I was also aware of Brown's in lacrosse, but was unaware that he also played basketball and competed in track. To win 10 letters is an incredible accomplishment - especially when you consider freshman were ineligible to play.