How the 2007 Backyard Brawl rewrote college football history

If Pitt doesn't upset West Virginia, the sport as we know it would look drastically different today

Last Saturday, Pitt and West Virginia played one of the more ghastly games of the college football weekend, combining for 422 yards in a 17-6 victory for the host Mountaineers.

It was the lowest combined point total between the longtime rivals in a game since 2007.

That meeting, of course, carried just a little more importance than their most recent one did.

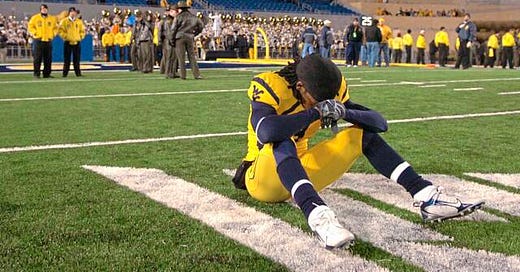

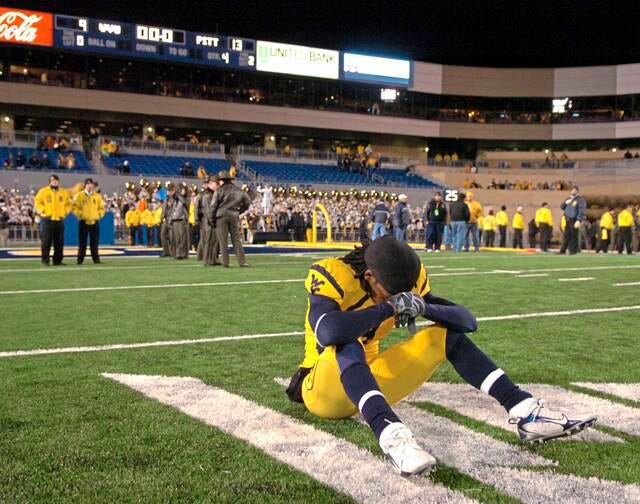

There are a handful of games throughout the history of college football that are so memorable and so transcendent that they’re known simply by a score. For the Panthers and Mountaineers, their 2007 clash is one that lives forever – as a perpetual taunt for the former and a source of eternal torment for the latter.

13-9

Pitt’s four-point win against West Virginia in the last game of the regular season for both squads is perhaps the defining game of a series with 106 all-time meetings dating back to 1895.

As a 28.5-point underdog on the road in one of the most notoriously hostile venues at the time for visiting teams, the 4-7 Panthers stunned the 10-1 Mountaineers, the nation’s No. 2 team. Playing a cover-zero all night that regularly featured eight- or nine-man boxes, Pitt held West Virginia and the sport’s most explosive rushing attack to just 101 yards on 41 carries. With star quarterback Pat White nursing an injured thumb that kept him out of long stretches of the game and limited him even when he was in, the Mountaineers seldom tested a vulnerable Panthers secondary that was selling out to stop the run.

By the final whistle, a team that had been averaging 41.6 points per game was held to just seven offensive points – the final two points came via a safety Pitt took in the final seconds to bleed out the clock and give the contest its much more memorable final score – by a defense that was giving up an average of 25.6 points per game and had previously allowed 44 points to Virginia, 48 points to Navy, 34 points to UConn and, just one week earlier, 48 to South Florida. Even FCS Grambling State managed to score more points (10) than the Mountaineers.

“You get to the fucking last game of the season and blow it,” Owen Schmitt, a star fullback on that West Virginia team, told SB Nation’s Alex Kirshner in 2017, “against the shittiest fucking team in the fucking world.”

Clearly, the searing sting of that loss was felt a decade later – and for good reason.

The Mountaineers’ setback not only cost them a chance at the program’s first-ever national championship, but it helped irrevocably shape the future of modern college football.

West Virginia

We’ll start with the first and most obvious party affected by the loss.

Had the Mountaineers won against the hated Panthers, they would have secured a place in the BCS national championship, where they would have faced off against No. 1 Ohio State. The Buckeyes had a hellacious defense that season, a unit that gave up an FBS-leading 10.7 points per game and featured future NFL players like Cameron Heyward, Vernon Gholston and Malcolm Jenkins, among others.

It’s difficult to say, even with whatever hindsight we have 16 years later, how that game would have gone. Ohio State ultimately lost to No. 2 LSU, the team that moved up after West Virginia’s loss, but there’s no guarantee it would have suffered a similar fate against the Mountaineers. It’s hard to envision an offense led by the immortal Todd Boeckman keeping up with a healthy White and Steve Slaton, what might be the most dynamic quarterback/running back pairing of the past quarter-century. Then again, LSU was a much bigger, beefier team than West Virginia, so the Buckeyes may not have had the same problems they did against the Tigers.

The Mountaineers’ mere participation in that game, win or lose, would have fundamentally altered the history of their program. There’s the heightened cachet and noticeable recruiting bump that comes with making a national title game, but much more than that, by playing for the sport’s ultimate prize, West Virginia would have held on to its coach.

Fifteen days after the shocking Backyard Brawl loss, Mountaineers coach Rich Rodriguez informed his players that he was leaving for Michigan. For a couple of years, Rodriguez had been one of the most sought-after coaches for any major vacancy after going 32-5 from 2005-07. The father of the zone read offense, Rodriguez, on the backs of White and Slaton, had offenses that were as exciting and high-scoring as any in college football at the time. He had turned down opportunities before – most notably, Alabama in 2006 before the Crimson Tide shifted its focus back to then-Miami Dolphins coach Nick Saban – but he couldn’t bring himself to say no to the Wolverines.

“Imagine what he does with limitless resources and tools,” Jed Drenning, a friend of Rodriguez’s, told the New York Times at the time of his departure. “Plug that into the Big Ten, and they’re not going to know what hit them.”

It didn’t quite work out that way. His stay in Ann Arbor was disastrous, ending after just three years and a 15-22 record, though given how Michigan did the year after his firing in the otherwise hilariously overmatched hands of Brady Hoke – going 11-2 and winning the Sugar Bowl – I’ve long argued that they simply gave up on him one year too soon.

But what if West Virginia did what so many expected it to do and beat Pitt? It’s very likely he wouldn’t have left.

Between that year’s Backyard Brawl and the national championship game was a gap of 37 days. If the Mountaineers are playing in that game, it’s highly improbable that 1) Rodriguez leaves his team behind for another job with a literal national title right in front of him and 2) Michigan waits until mid-January to hire a new coach, especially with national signing day less than a month away.

In this scenario, Rodriguez stays at West Virginia and regardless of whether he beats Ohio State, he heads into 2008 with White, Slaton, standout freshman running back and OG YouTube mixtape sensation Noel Devine, and a number of important pieces from the defense. With that returning talent and a watered-down Big East making up most of its schedule, the Mountaineers undoubtedly would have been one of the national championship favorites.

From there, who really knows? Rodriguez is a native of the state who graduated from West Virginia, which gives him the kind of ties that can sometimes steer someone against leaving for brighter, more prosperous pastures, but Rodriguez was also an ambitious coach with a wandering eye who reportedly didn’t have a great relationship with university administration. If it wouldn’t have been Michigan, it very well could have been somewhere else.

But there’s one more thing to consider. In the years immediately after that 2008 national championship, the chaos of conference realignment was reignited. For the Big East, that means the losses of Pitt and Syracuse to the ACC in 2011, moves that thrust West Virginia into survival mode and sent it scurrying into the arms of the Big 12.

If realignment has taught us anything, it’s that it’s fickle. A long-term decision that affects a league and its members for decades is often made based on how attractive a school looks in a small, fleeting slice of time.

At that point, the Mountaineers had a men’s basketball program coming off a Final Four in 2010 and a football program that made a national championship and, potentially, even won it. That round of realignment was a naked grab at TV markets in the hope of adding cable subscribers and additional revenue, so the school representing one of the smallest and poorest states in the country may have only been so desirable, but their excellence in the two major-revenue sports would have been too much to ignore. If it has that football national title berth in hand, perhaps the ACC did what it ultimately did in 2012 with Louisville and eschews its misguided academic snobbery and adds West Virginia, either along with Pitt and Syracuse or in place of one of them. Or, for whatever reason, maybe that success catches the eye of the Big Ten or SEC. At the very least, it’s possible the Mountaineers don’t end up in an awkward marriage of necessity in a league where they’re an extreme geographic outlier, with the closest member to them for more than a decade nearly 900 miles away.

No school and athletic program was impacted by the game more than West Virginia, but it was far from the only one.

LSU

If the Mountaineers win and Rodriguez turns down Michigan – if he’s even offered at all, given the timing – the Wolverines would have likely turned their attention back to the man who was linked to the vacancy more frequently than anyone else: Les Miles.

The LSU coach was in his third season at the school and, at that point, had amassed a 32-6 record. His team that season was exceptional, with 17 future NFL players on defense alone. Talented as that squad was, it was the beneficiary of West Virginia’s late-season stumble and became the first (and only) two-loss team to ever make a BCS title game.

So instead of Rodriguez being the coach with the month-long wait to play for a championship, it was Miles.

All these years later, it’s still unclear whether Miles was ever offered the Michigan job. John U. Bacon, a best-selling author who has written extensively about Michigan, has said Miles wasn’t. Skip Bertman, LSU’s AD at the time, has said Miles was, but turned down the job despite being offered a pay raise to make the move. Miles himself has said he was never offered the position. In all three instances, there’s some self-interest at play, meaning the information should be taken with a grain or two of salt.

With ESPN’s Kirk Herbstreit reporting the morning of that year’s SEC championship game between LSU and Tennessee that Miles would be the next Michigan coach, Miles held an impromptu press conference to shoot down the speculation.

“I’m the head coach at LSU,” he said. “I will be the head coach at LSU. I have no interest in talking to anybody else. I’ve got a championship game to play and I’m excited about the opportunity of my damn strong football team to play in it. That’s really all I’d like to say.”

(I’m not sure what I enjoy more about that presser – that he didn’t bother to sit down or that he punctuated it with a very clearly insincere “Have a great day.” It’s all wonderful.)

It was a stern, forceful denial, but, like any deft coach, Miles left himself some wiggle room in case circumstances changed. It wouldn’t matter. The Tigers went on to win that game, 21-14, and with it, any questions about Miles and the Michigan job became moot.

If they hadn’t, though, or had West Virginia simply won the previous week, it’s quite possible Miles would have left for his dream job at a school where he played and coached. It would have altered the immediate future of the Wolverines, who wouldn’t have to undergo the drastic and rapid shift from a pro-style offense to Rodriguez’s spread scheme. With a Michigan Man™ at the helm, they likely don’t go through the significant coaching turnover they experienced going from Rodriguez to Hoke to Jim Harbaugh in a span of six years. If Miles excelled in that role or kept Michigan close to what it had been, does Harbaugh ever return to his alma mater to save it?

And what becomes of LSU? There would have been no shortage of good or qualified candidates. When Bertman hired Miles three years earlier, he had looked at Virginia Tech’s Frank Beamer (who turned it down), Louisville’s Bobby Petrino (who rubbed him the wrong way) and Steve Spurrier (who grew impatient and accepted the South Carolina job a month earlier). Perhaps he makes another run at Spurrier, who would be in line to lead a better, more well-resourced SEC program. Or maybe he decides the abrasive Petrino, who ended up leaving the Atlanta Falcons in his first season there that December, and his high-powered offense is worth the headache, especially since Bertman stepped down the following year and would have only had to deal with Petrino for so long.

It wasn’t just programs who were affected by West Virginia’s loss. There were a handful of high-profile individuals, too, whose lives were changed.

Terrelle Pryor

College recruiting coverage was already mainstream by the mid-late 2000s, but Pryor was one of the first high-school prospects who felt truly transcendent.

At 6-foot-6 and 235 pounds, Pryor dominated at Jeannette High School outside Pittsburgh, becoming the first player in Pennsylvania high school history to throw for 4,000 yards and run for 4,000 yards over the course of his career. He was billed as one of the most talented quarterback recruits in recent memory, a program-changer who would make whatever school that was fortunate enough to land his services a championship contender any year he was under center.

For some time, there was one school that was considered a favorite to get a commitment from Pryor – West Virginia.

The pairing made sense. The school’s Morgantown campus is only about an hour and 15 minutes from Jeannette, but more than that, the Mountaineers offered Pryor a situation in which he would thrive. Rodriguez’s zone read offense had blossomed into the talk of college football by utilizing athletic and speedy dual-threat quarterbacks who could make quick decisions that constantly put opposing defenses on their heels. This effectiveness was best personified by White, who went 27-4 as a starter from 2005-07 and helped transform the Mountaineers from a Big East power into a national title contender.

For all of White’s excellence, though, he wasn’t Pryor. While possibly quicker, White was 6-foot-1 and a relatively gangly 192 pounds. He could run around virtually anyone in college football, but he didn’t possess the kind of physicality that Pryor did and didn’t have as strong of an arm. West Virginia was already virtually unstoppable with White at quarterback. With Pryor, it would have been something even more than that.

Had Rodriguez stayed and Pryor committed to West Virginia, he likely would have sat behind White in 2008 while still coming in for certain series and packages. Perhaps the arrival of Pryor would have convinced Slaton to stay for one more year. That success would have lasted beyond the Mountaineers’ iconic duo graduating after that 2008 season. Pryor would have assumed the starting role and been paired with Devine, giving West Virginia perhaps the most athletic quarterback/running back tandem in the sport’s history – and in an offense perfectly tailored to its strengths. That’s not even accounting for the fact that he would have had the likes of Tavon Austin, Jock Sanders and Stedman Bailey to throw to over the course of his career.

If projecting continued double-digit-win seasons for Rodriguez after losing White and Slaton seems like a reckless assumption, it’s really not. If anything, the offense might have been even better.

When Rodriguez left for Michigan, Pryor removed West Virginia from his list of finalists and inserted the Wolverines in its place. He had a strong bond with Rodriguez and was a perfect match for his offense, leaving some to wonder whether he’d end up in Ann Arbor and make Rodriguez’s transition much smoother than it was projected to be.

"If that kid comes, he's probably more important than Rich," legendary West Virginia coach Don Nehlen, a former Michigan assistant coach, told the Associated Press after Rodriguez’s departure from Morgantown.

Ultimately, Pryor chose Michigan’s archrival, Ohio State. He took over for Boeckman as the starter by the end of September of his freshman year and over his first three seasons, he led the Buckeyes to a 31-5 record, two Big Ten championships and three BCS bowl berths.

In Dec. 2010, though, the NCAA suspended Pryor and four of his teammates for the first five games of the 2011 season for selling memorabilia – rings, jerseys and awards – they had earned in their time in Columbus. ESPN reported Pryor made between $20,000 and $40,000 autographing memorabilia in 2009-10, a claim denied by Pryor’s attorney.

By June 2011, and despite having one more season of eligibility, he had withdrawn from the university and was relegated to the NFL’s supplemental draft, a far cry from the heights once envisioned for him.

Ohio State

Even before Pryor left Ohio State, the problems engulfing the Buckeyes’ storied football program were beginning to mount.

Coach Jim Tressel was made aware of the memorabilia arrangement in April 2010, but failed to notify the university’s compliance office or the NCAA about it. The NCAA later accused Tressel of lying and withholding information to keep the impacted players on the field, which college sports’ governing body deemed to be major violations.

In late May 2011, Tressel resigned after 10 seasons at the school.

(As a side note, it’s absolutely wild to read back on some of the coverage and reaction to his story from the spring of 2011. It was billed by some as perhaps the biggest scandal in the history of college sports. Six months later, it was revealed that Jerry Sandusky had sexually abused children for years and the idea of what actually constitutes a scandal was rightfully recalibrated).

While Pryor wasn’t the only player involved in the indiscretions, he was a part of a series of missteps, at least as far as they’re defined by the NCAA’s archaic model at the time, that led to Tressel ouster. Were he at West Virginia instead of Ohio State, it’s likely that never occurs.

And if it doesn’t happen, how much longer does Tressel stick around Ohio State? He had already established himself as perhaps the best non-Woody Hayes coach in the Buckeyes’ proud history, with a 106-22 record, a national championship, two additional national title game appearances and six Big Ten championships to his name.

In his final six seasons, his teams went 66-11 and never won fewer than 10 games in a season. The end can come quickly and unexpectedly for even the sport’s top coaches, but at 57 years old, Tressel had shown few, if any, signs of slowing down. While his offense was becoming increasingly outdated, and certainly would qualify as such under today’s standards, there’s a good chance that he, like a number of elite coaches, would have adapted. Or even if he didn’t, he would have had at least several more years at the helm in Columbus.

Had that been the case, it wouldn’t have created an immediate opening for one of the biggest coaching free agents in modern college football history.

Urban Meyer

I hate to end on such a dour note, but alas, here we are.

After a one-year sabbatical, Meyer took over at Ohio State following the awkward one-year gap between Tressel’s resignation and Meyer’s hiring, a year in which Luke Fickell – who has turned out to be a damn fine coach himself – was the program’s interim coach.

It made perfect sense for Meyer to end up with the Buckeyes. He was an Ohio native who earned a master’s degree from Ohio State while working as a graduate assistant with the football program. He still had deep ties to and a great affection for the state. Most of all, it is a place better built than perhaps anywhere else to win. Since 1972, the Buckeyes have failed to make a bowl game just four times, one of which was self-imposed. For the sake of comparison, Alabama has failed to do so six times, Michigan seven, Oklahoma 10, Texas 12 and USC 13.

But if Tressel never leaves Ohio State in shame in 2011, how long does Meyer wait around for a plum gig to come open? And if he doesn’t feel like waiting around for Tressel to retire or step aside, where does he end up?

Meyer resigned from Florida after the 2010 season to focus on his family and health, which is probably truthful in some ways, but wasn’t enough to swallow his ferocious desire to get back into coaching at some point.

When looking over the vacancies from 2011, 2012 and 2013 – let’s safely assume Meyer was only willing to wait on the proverbial sidelines for so long – there are a few possibilities that stand out. Wisconsin, Ole Miss, UCLA likely wouldn’t be big-time enough for him. Texas A&M wasn’t quite the infrastructural and financial behemoth it is now after a decade of SEC membership. Auburn’s too much of a self-destructive mess, even for Meyer. Same for Tennessee. Penn State would be a potential fit under normal circumstances, but its attractiveness was severely diminished by the aftermath of the Sandusky scandal.

While there are other schools that might have fired a coach they otherwise wouldn’t have if they thought they had a chance at Meyer, that leaves two programs from that time as distinct and fascinating-as-hell options – Texas and USC.

As is the case for any of these programs and individuals, we’ll never know what would have really happened in this alternate universe. And it’s all because of the shittiest fucking team in the fucking world.

(Photos: Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, West Virginia athletics, Ohio State athletics)

This was fascinating. I had never contemplated the 13-9 game in that fashion. It's so weird to look back at the Ohio State / Terrelle Pryor incident as a scandal - it's almost quaint considering today's game with NIL. (Apologies to the SMU boosters of 40 years ago.)