Dan D’Antoni’s Marshall career is over, but his analytics revolution continues

Ten years after taking over the Thundering Herd, college basketball looks much more like his 3-point-centric teams than it did when he first arrived

As a reporter, there are certain moments from press conferences that stick with you.

Admittedly, most post-game interviews with coaches and players are a drag, an often-fruitless-yet-necessary exercise at trying to extract some tiny smidge of insight from people who, for a variety of reasons, are routinely unwilling to do so.

In that setting, when something truly entertaining or revelatory comes along, it has a way of lingering somewhere in the back of your mind for weeks, months and sometimes even years after it happens.

All of this is a long-winded way of going back to Dec. 28, 2016. On an otherwise non-descript post-Christmas night in Western Pennsylvania, Pitt survived an upset bid from Marshall for a 112-106 win to improve to 11-2 in what would be an ill-fated first season of Kevin Stallings’ Murphy’s Law of a coaching tenure at the school.

After the dizzying, up-and-down game, Marshall coach Dan D’Antoni stepped to the dais. Matt Gajtka, a thorough and thoughtful local reporter in Pittsburgh who primarily covered baseball and hockey, asked D’Antoni why his team didn’t work the ball into the paint more. After all, the Thundering Herd had attempted 30 3-pointers and made just 10 of them, seemingly questionable shot selection that could have cost it a game it lost by just six.

D’Antoni flashed a wry smile and shook his head. An artist has just been given paints and a blank canvas.

“You’re old school, aren’t you? Do you watch the NBA ever?...You see those top three teams. Golden State – do they work it in? My brother in Houston, the biggest turnaround in the league – do they work it in? You can go get any computer and run what the best shots are and it will tell you the post-up is the worst shot in basketball. If you want to run down and try to get it in there to shoot over somebody then you’re beating analytics. The best shot in basketball is that corner 3. The next-best shot is any other 3. Other than free throws, which we try to do…when you get to the foul line, you score 1.5 points every time you go to the foul line in the pros. It just trickles down. It’s the same thing for college kids.”

D’Antoni took a pregnant pause for a second or two, a time in which Will Graves, the excellent Pittsburgh-based Associated Press sports writer, tried to ask a question. But the masterpiece wasn’t yet complete.

“I ain’t finished my daggone analytics story yet. You have to go to bed or something? Or are you going out? If I can get to a layup and it’s clean – it’s not one that’s highly contested – it’s 1.8 [points per attempt]. It’s 1.3 from that corner, 1.27. Do you know what a post-up is, with a guy standing over top of you? It’s 0.78. So you run your team down there and we’ll see how long you can stay with teams that play the other way. You’ve seen it in the NBA. The last two championship teams have been Cleveland and Golden State. What do they do? You don’t see anybody post up. They spread that thing out and go. I changed a long time ago. I coached for 15 years like a dummy, running down there real hard so I can get it in there for the worst shot in basketball. I didn’t even know what I was doing. The short version of my answer is no.”

(At the time, I butchered the first part of his second block quote, typing it out as “my damn analytics story” instead of the much funnier and more accurate “my daggone analytics story.” Almost eight years later, it’s still one of the biggest regrets of my journalism career.)

By the next morning, D’Antoni’s quote had gone viral and he had become a darling of the burgeoning analytics-focused movement in both the NBA and college basketball.

D’Antoni had lost that game, but more than that, and certainly unbeknownst to him, he won a fan. For years, I would always check the score of a handful of programs in which I had a vested emotional interest – the team I grew up rooting for, my alma mater and, oddly enough, Marshall, where that basketball mad man and his sheet listing the per-possession value of every conceivable shot attempt were conducting one of the sport’s most riveting experiments.

Last month, it came to an end.

On March 25, Marshall announced there would be a “leadership change” atop its men’s basketball program, but offered no specification on whether he had resigned, retired or been fired. Some who cover college basketball reported that D’Antoni, coming off a 13-20 season, had been forced out.

"This has been an inspiring decade of Marshall Basketball under the leadership of Coach D'Antoni," Marshall athletic director Christian Spears said in a statement. "His commitment to Marshall is unrivaled and his legacy will be honored for years to come. He built a program that plays for a community who deeply cares about him and our student-athletes. We wish him the very best and look forward to seeing him as he continues to support the program he built.”

It signaled an abrupt and inglorious end to a largely successful tenure in which Marshall reached heights it hadn’t in years.

Just as importantly, though, the Herd were a hell of a lot of fun to watch doing it.

How “the worst thing you’ve ever witnessed” became the best

Though D’Antoni was a West Virginia native and Marshall graduate, giving him the kinds of ties university leadership often wants from its most visible employees, he was a highly unconventional choice to take over the program for which he once played.

When he was hired by his alma mater in 2014, D’Antoni hadn’t coached at the college level since 1971. He spent 30 years coaching at a South Carolina high school., before making the jump in 2005 to the NBA, where he worked as an assistant under his brother, Mike, for the Suns, Knicks and Lakers. There was plenty of coaching experience, but just how much of it was relevant to his new gig?

Not only was he not Marshall’s first choice, but he wasn’t even the first D’Antoni it wanted. The Herd made a longshot run at Mike D’Antoni – like his older brother, a former Marshall player – who was in what would be his second and final season coaching the Lakers. It was an extended courtship, lasting 30 days before he, as you would expect from the head coach of the Los Angeles Lakers, turned them down.

Sensing it wouldn’t land the younger D’Antoni, Marshall formulated contingency plans, many of which ultimately backfired. Originally, the job was offered to Eastern Kentucky coach Jeff Neubauer, who accepted. However, according to the Herald-Dispatch in Huntington, W.Va., a prominent Herd booster met with the university’s president and urged him to hire Dan D’Antoni. Marshall called Neubauer, who was en route to Huntington, and told him it had changed its mind.

While the Herd interviewed D’Antoni, it offered the job to Stephen F. Austin coach Brad Underwood (now the very successful coach at Illinois) and began engaging in negotiations with his agent. Unbeknownst to Marshall, Underwood was more interested in the vacant Southern Miss job and was using the Herd as leverage to get a better deal from the Golden Eagles. Having been played, the Herd reached back out to Neubauer, who, not surprisingly, gave them a quick “no.”

Attention then shifted back to Dan D’Antoni, who was set to interview in Huntington with Marshall officials. Before he got the chance to fly across the country, he was offered the job.

News of the hire was met with skepticism to outright derision, with Marshall entrusting its basketball future to a 66-year-old who hadn’t coached in college since Richard Nixon’s first term as president.

Journalist Jeff Goodman, then of ESPN (and who I feel like I pick on a bit too much with these coaching reactions), tweeted that Conference USA coaches were texting him “at a furious rate downright giddy” about the Herd’s choice. Gary Parrish of CBS Sports responded to Goodman by noting he had received a text from an NBA source who believed D’Antoni at Marshall “will be the worst thing you’ve ever witnessed.”

Before D’Antoni had ever coached a game, recruited a player or even stepped up to the podium for his introductory press conference, it had been determined – this marriage not only had the potential to be a disaster, but was very likely to be one.

D’Antoni had other ideas.

The rise of #Danalytics

As D’Antoni was unveiled as Marshall’s next head coach, he did what any unpopular hire should and injected a little humor into his first public comments to an uneasy fan base.

"When we were here, if I remember correctly, this was a basketball school," he said. "I don't know what happened when I left."

The Herd wasn’t some kind of hopeless, perennial loser when D’Antoni took over. In fact, two years before D’Antoni returned home, Marshall had finished off its third consecutive season with at least 20 wins.

The program, however, had consistently fallen short of the goals that define teams at that tier of college basketball. Despite having a handful of successful coaches come through Huntington, particularly Billy Donovan and Dana Altman, the Herd hadn’t made the NCAA Tournament since 1987. Marshall had some inherent shortcomings that limited its ceiling, namely being the second-biggest program in one of the smallest and poorest states in the country.

For whatever he lacked in college bona fides, D’Antoni returned to his home state with a plan and a larger basketball philosophy that could mitigate at least some of the challenges the Herd had faced for decades.

D’Antoni was coaching high school ball down in South Carolina when the 3-point line was added at that level. He began having lengthy conversations with his younger brother, who had been playing and coaching in European professional leagues after the 3-pointer had been introduced there. Unlike others who saw it as a gimmick, Mike immediately embraced it. Seeing the success he had, his colleagues and competitors eventually followed suit. Mike relayed the findings on to his brother – the team that won the most overseas were the ones that shot the most 3s.

It was then that D’Antoni realized, as he mentioned in his 2016 tangent, that he had been coaching like a dummy this whole time. He scrapped the offensive gameplans he had been utilizing for years and built his teams around an ability to get up the court quickly, spread the floor and take the shots worth the most points.

"It's like playing poker and they've got a deuce and I've got a 3," he said in a 2017 interview with the Marshall athletics website. "Guess what? I win."

It didn’t long for his system to take hold at Marshall. In his first season in 2014-15, the Herd attempted 788 3s, a school record at the time. It shattered that mark a year later, jacking up 985 shots from beyond the arc.

Marshall’s schematic shift was occurring at a fortuitous time. The Herd’s approach of building its offense around 3s, shots closest to the basket and free throws was rapidly becoming the norm in the NBA, but the college game lagged behind.

While his offense was regularly framed as some new-school, cutting-edge phenomenon, D’Antoni saw it as something of a throwback to when he played in the late 1960s, when players, even without a shot clock, didn’t deliberate for the sake of it and would fire up an open shot when they got it in a free-wheeling game.

“Then it became more of a coached game,” D’Antoni said in 2018 to WV MetroNews. “Almost like if you were a painter. You’re painting A to B to C to D and stay within the lines, you know? I prefer the freelance — he gets up, he has an empty canvas, he doesn’t have directions. You just start putting it on the canvas.”

Though an imperfect measurement for offensive effectiveness, especially for some of D’Antoni’s beloved metrics, his teams pushed the pace and scored frequently, finishing second among all Division I teams with 86 points per game in just his second season at the helm.

In his first five seasons, Marshall never had 3s account for fewer than 42.2% of its total shots. They pushed the pace year-over-year in a way few programs did nationally, finishing in the top 20 of more than 360 Division teams in tempo, according to KenPom, in his first nine seasons, a run that included seven appearances in the top 10. In those same nine years, the Herd never finished lower than eighth nationally in average possession length.

Initially branded as #Danalytics, it later became known as “Hillbilly Ball,” though as a sucker for a well-executed pun, I have to admit I like the former better.

By implementing that philosophy and mindset, Marshall did what so few thought it would under D’Antoni – it won.

Over his 10 years with the Herd, D’Antoni’s teams went 177-148, making him the second-winningest coach in program history, behind only Cam Henderson, who the court at Marshall is named after. Three of the top five scorers in program history played under D’Antoni – Taevion Kinsey (No. 1), Jon Elmore (No. 2) and C.J. Burks (No. 5). Even his second-to-last team, in 2022-23, won 24 games, the program’s most regular-season victories in 75 years.

The unquestioned height of that decade in charge came in 2018. That season, Marshall went 25-11 and won the Conference USA Tournament to advance to the NCAA Tournament for the first time in 31 years. It only took a few days for that accomplishment to be surpassed. As a No. 13 seed, the Herd knocked off No. 4 seed Wichita State to earn the first NCAA Tournament victory in program history…despite attempting an uncharacteristically low 23 3s.

“I’ve seen a lot of college teams play,” Marshall star guard Jon Elmore said during that 2018 tournament run. “I might be biased, but I think we have the most fun.”

Dan D’Antoni will be gone from college basketball, but far from forgotten

As is the case far too often, the good times weren’t built to last.

Marshall never made it back to the NCAA Tournament under D’Antoni and slipped further from the apex it enjoyed under him, finishing with a losing record in two of his final three seasons. Even his once-humming offense started to sputter. Last season, the Herd shot just 31% from 3, ranking it 317th of 362 Division I teams.

The shots were still as efficient as ever – the math was right on those – but they simply stopped falling at the same rate they used to.

The program had taken a noticeable step back, D’Antoni was 76 and Spears, an eager and relatively new athletic director, had an opportunity to make his own hire for one of the school’s major-revenue programs.

When Cornelius Jackson, a former Marshall player who had served as an assistant under D’Antoni since 2017, was elevated to the full-time head coaching role, D’Antoni was supportive, not bitter.

"My car is not pulling out of Huntington and I hope to see you as we support Marshall, the Tri-State, West Virginia and, of course, our new head coach,” D’Antoni said at Jackson’s introductory presser. “I'm so proud of Corny! He's going to be great for our Thundering Herd!"

Though he’ll no longer be an active college head coach, D’Antoni’s imprint will remain on the sport, as the movement of which he was a notable part has helped the sport evolve. The kinds of shots that caused some to wonder whether he had lost his mind have come to define some of college basketball’s top teams and programs.

In D’Antoni’s first season, 2014-15, Marshall finished 27th in percentage of total shots coming from 3, with only two Power Five or Big East teams ahead of it (Villanova at 22nd, Creighton at 24th). By the end of the 2023-24 season, four such teams appeared in the top 20 – BYU (4th), Creighton (8th), Villanova (11th) and Alabama (19th), three of the four of which made the NCAA Tournament and the last of which made the program’s first-ever Final Four. The mark that ranked the Herd 27th in 2015, with 42.2% of its shots coming from 3, would have placed it 54th this season.

Villanova’s two championship teams under Jay Wright, in 2016 and 2018, took a similarly analytics-heavy approach in which 3s and free throws were uncommonly valued. Nate Oats, who just led Alabama to that aforementioned Final Four, is an unabashed advocate for using math to dictate offensive strategy, even employing a sports analytics firm to give his coaches and players real-time suggestions during the tournament on the best shots to take. During this most recent coaching carousel, the two highest-profile openings – Kentucky and Louisville – hired coaches whose teams finished last season second and third in 3 attempts per game.

If nothing else, it makes for one hell of a daggone analytics story.

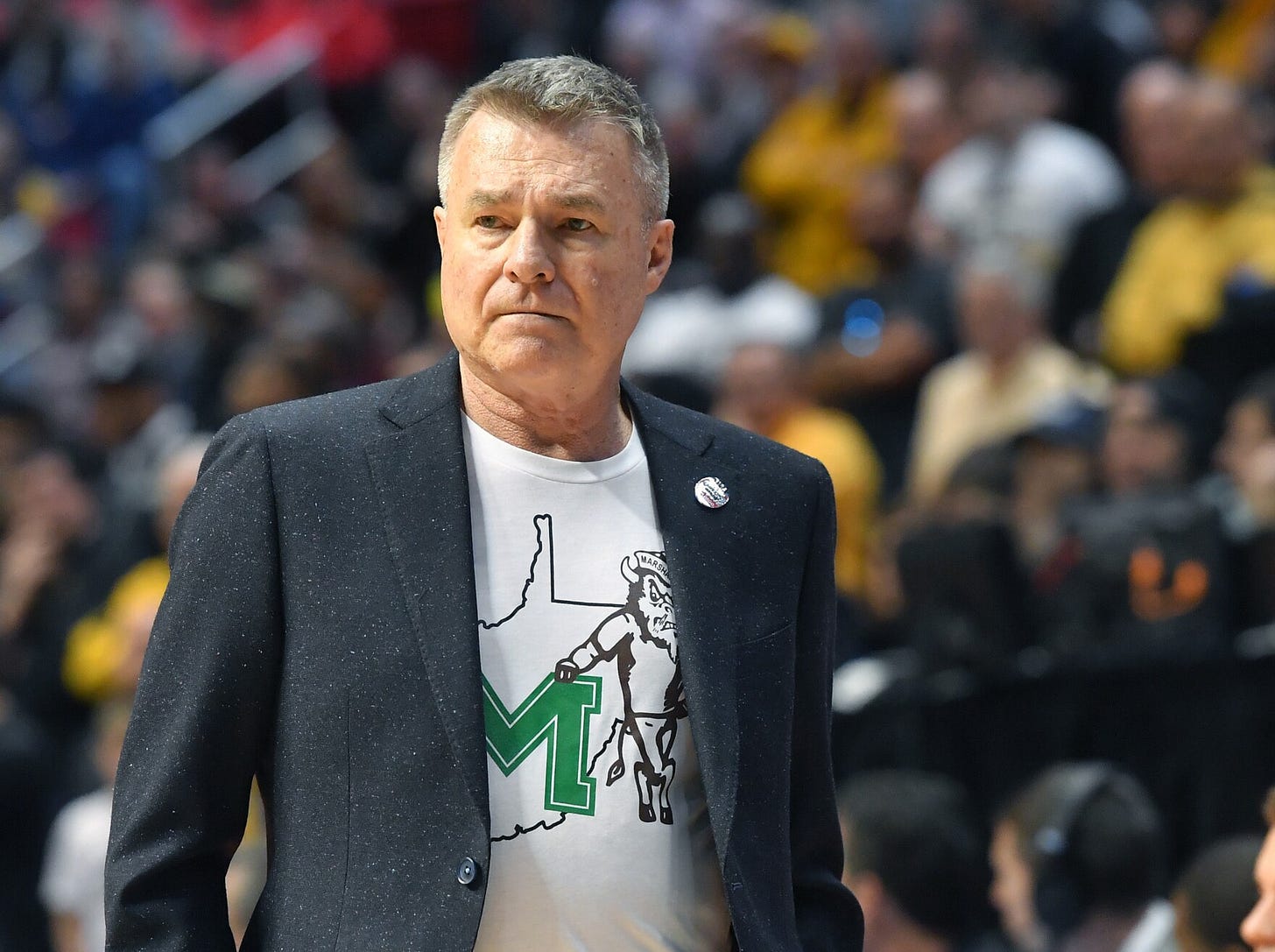

(Photo: Marshall Athletics)