Bill Walton embodied the best of college basketball

As a player, he showed us the athletic excellence we crave. As a broadcaster, he reminded us that this is all supposed to be fun

On Monday afternoon, I encountered a familiar and uniquely post-2010 anxiety – I saw someone over the age of 60’s name trending on social media.

In at least some instances, it’s a false alarm. Perhaps they were simply part of a viral story, accomplished something notable or were the object of nostalgia that day, with some engagement-hungry account posting a highlight reel of their playing days with a caption along the lines of “Earl Campbell was a problem.”

On this day, though, my worst fears were realized. Bill Walton’s name was among the most tweeted phrases that day because he had just died.

Walton left the earth he loved so dearly on Monday at 71 years old, succumbing to a prolonged fight with cancer before the disease did what it has to so many millions of others.

If reaction to Walton’s death indicated anything beyond near-universal admiration of the man, it was that he meant a lot of different things to a lot of different people.

For some, he was the dominant national champion who was part of the UCLA machine of the 1960s and 1970s. For others, he was the ill-fated NBA star, the catalyst of the transformative 1977 Portland Trail Blazers championship squad and a lingering ‘What if?,’ someone who enjoyed a hall-of-fame career but could have been something much greater had it not been for debilitating injury after debilitating injury. For many my age, we associated his face and voice not on the court, but just to the side of it, offering commentary on games in a way only he could. And lest we forget his status as the nation’s foremost, and certainly tallest, Deadhead.

If there’s a throughline to be found in this, particularly for a newsletter like this that delves into the world of college sports, it’s this – there are few figures in the history of the sport who better embodied what’s great about men’s college basketball and what it can be than Walton.

Bill Walton the player was a legend

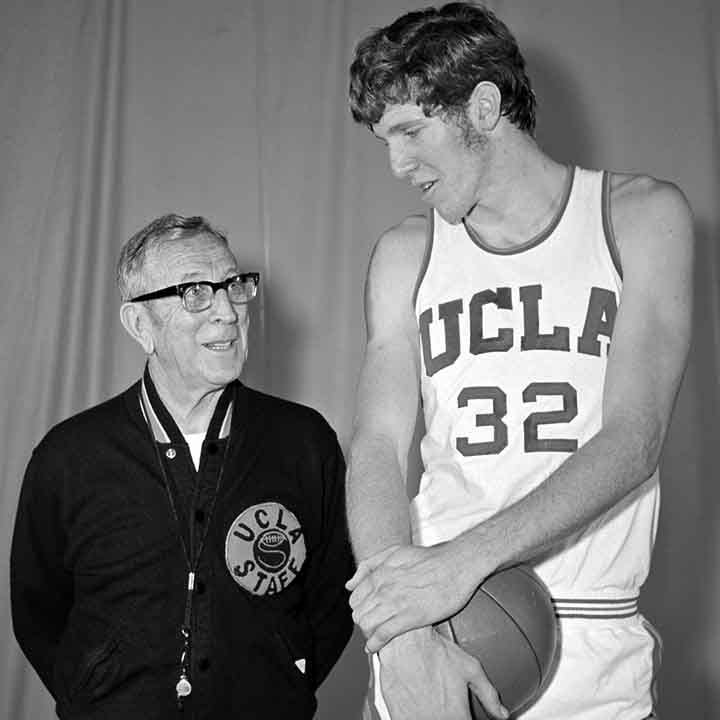

By the time Walton arrived at UCLA in 1970, the Bruins’ basketball program was already a juggernaut in the process of constructing a dynasty that will almost assuredly never be matched.

Under coach John Wooden’s expert and careful watch, UCLA had won four consecutive national championships and six of the past seven titles. In 1970-71, while Walton was relegated to the school’s freshman team due to NCAA rules of that era, it captured its fifth in a row.

He’d soon make himself known. While Walton was still at Helix High School in his hometown of La Mesa, Calif., Wooden sent assistant coach Denny Crum, later a two-time national title winner as a head coach at Louisville, down to watch him in person. Initially skeptical of the 6-foot-11 redhead, Crum returned to Westwood amazed.

"I came back and told Coach Wooden that this Walton kid was the best high school player I'd ever seen," Crum said years later. "We were sitting in Coach Wooden's office, and he got up and closed his door and said, 'Denny, don't you ever make that stupid statement again. It makes you look like an idiot to say that some red-haired, freckled-faced kid from San Diego is the best high school player you've ever seen. First of all, there's never, ever been, since I've been here, a major college prospect from San Diego, let alone the best player you've ever seen.'"

Walton was so good, he was able to prove one of the sport’s all-time greatest coaches wrong (while simultaneously proving another one right).

In each of Walton’s first two seasons on the varsity team, the Bruins went 30-0 and won the national championship. It wasn’t until the 14th game of his senior season in 1973-74 that UCLA lost a game, with a record 88-game win streak famously snapped by Notre Dame. By that point, Walton had carried an even more impressive run. Between his two-plus seasons with the Bruins, an undefeated season on the school’s freshman team and his blemish-less final two years of high school basketball back in the San Diego area, Walton had a personal 142-game win streak.

His brilliance was perhaps best exhibited in the second of that pair of national championships. In an 87-66 throttling of Memphis State in the 1973 NCAA title game, Walton scored 44 points on an astonishing 21-of-22 shooting performance from the field. It was nearly even more impressive, as four of his baskets were dunks that were wiped off the board due to a baffling NCAA rule at the time banning them. Still, even without those extra eight points, his scoring total is still the highest ever in a national championship game and his field goal percentage is a single-game Division I record for a player who made at least 20 shots.

To anyone who watched him play – or anyone who has spent enough time watching his highlights on YouTube or NBA TV – Walton was one of the sport’s original unicorns, someone whose game seemed so plainly ahead of his time. There was his sheer size, of course, but he possessed exquisite touch around the basket, had remarkable footwork, superb court vision and, maybe most dangerously for opponents, remains one of the best passing big men to ever play.

Even as he was still developing, that collection of traits was on full display at UCLA. He won the Naismith Player of the Year award in each of his three varsity seasons, making him one of only two players ever to claim the honor three times (Ralph Sampson’s the other). Wild as it is to comprehend, especially in today’s much more transient college game, UCLA had either Kareem Abdul-Jabbar or Bill Walton playing center for it in six of eight seasons from 1966-74.

For all he achieved there, Walton’s time with the Bruins wasn’t without conflict, particularly with Wooden. The free-spirited big man was occasionally at odds with his conservative, straight-laced coach. As a freshman, Walton sported long locks and initially refused to cut them when Wooden asked him to. Wooden simply responded by saying “We’ll miss you,” three words that were enough to get Walton on his bike to a nearby barber. In 1974, Walton and a group of protestors layed down on Wilshire Boulevard near the UCLA campus to try to stop traffic as a larger protest against the United States’ ongoing military involvement in Vietnam. Walton was among those arrested and had to be bailed out of jail by his coach. When Wooden arrived, his star center explained to him why he was protesting, noting that many friends of his had been killed in the war, to which Wooden responded that he, too, was against the war, but that “protesting is not the right way.”

A college career with so many triumphs ended on a somewhat dour note, with UCLA falling to David Thompson and eventual national champion N.C. State in the Final Four, 80-77 in double overtime. Decades later, the loss stayed with him.

"That failure has plagued me, and will," he said in 2015 to NCAA.com. "It is a stigma on my soul, and there's no way I can get rid of it."

In reality, he had no reason to feel any bit of shame. He finished his college career with an 86-4 record, with those four losses coming by a combined 13 points (and none of them being decided by more than five points).

While Abdul-Jabbar is widely (and rightly) considered the best player in college basketball history, Walton isn’t too far behind, with a legacy at the NCAA level that, all these years later, still largely manages to outshine an NBA career in which he won two championships and an MVP.

Bill Walton the broadcaster was a necessary voice

Much of Walton’s career took place during an era that’s often relegated to the shadows of the sport’s history for a number of reasons, from tape-delayed or outright blacked-out games to drug use among players to the country’s widespread reluctance at the time to embrace an overwhelmingly Black game.

What allowed Walton to resonate well beyond his final game in 1987 wasn’t just his on-court brilliance, but his work as a broadcaster.

Walton began as a color commentator with CBS in 1990 and was an on-air voice for the NBA for the next 19 years for various networks and teams, a time in which he became one of the most prominent figures in the league’s media coverage.

For someone like me who later embraced Walton for his quirkiness as a fixture of late-night college basketball, looking back on his time as an NBA analyst can be a bit jarring. For much of that nearly two-decade stretch, he was an acerbic critic of players, trafficking in hot takes and lazy stereotypes that sometimes seemed oddly personal. Walton famously had a longstanding feud with Shaquille O’Neal, though that beef might be more attributable to O’Neal’s well-known pettiness than anything particularly odious Walton did or said.

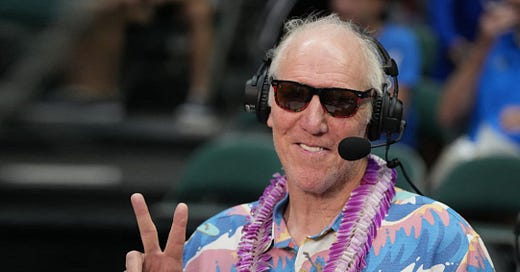

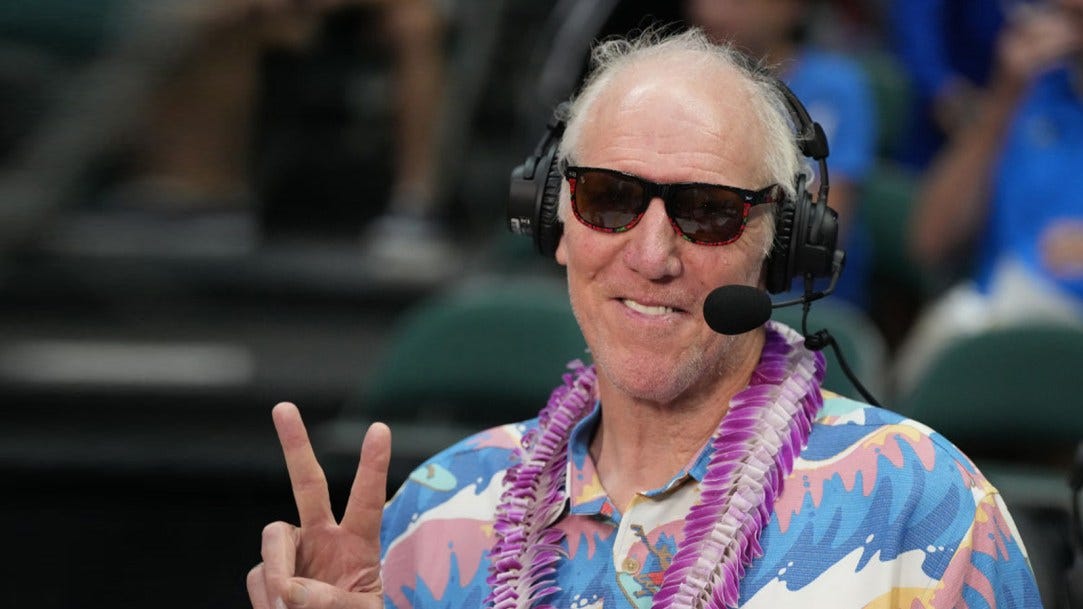

After a brief time away dealing with ongoing health issues, Walton returned to television in 2012, covering college basketball for ESPN and the Pac-12 Network. It’s then that he became the personality so many were remembering so fondly Monday.

Walton had shown glimpses of it before. He was charmingly eccentric throughout his playing career and even toward the end of his run covering the NBA for ESPN, he let his freak flag fly a bit, like when he compared then-Phoenix Suns big man Boris Diaw to Beethoven.

In his final 12 years on television, the audience got to see something much closer to the true Walton. With the benefit of calling games while much of the country was asleep or preparing to go to bed, Walton’s broadcasts would invariably go off-topic, with discussions of subjects that had little, if anything, to do with basketball in general, let alone the game unfolding in front of him.

Here’s a small sampling:

He ate a cupcake with a still-lit candle atop it on live TV.

He compared a Kansas team during the Maui Invitational in 2019 to a volcano, a waterfall, and a breaching whale.

During a UCLA-Washington game sometime in the Steve Alford Era in Westwood, he discussed a theoretical fight between bruins and huskies.

He attempted to sound like a wildcat during an Arizona game in Feb. 2020, a couple of weeks before COVID shut down the world.

He rubbed dirt on himself that he had gathered earlier that day from Temecula during a break in the action of an Oregon-Arizona game in 2016, much to the amusement and confusion of the fans sitting behind the broadcast table.

He took a brief shot at play-by-play duties in February 2020, acting as though he was broadcasting an early 2000s Indiana Pacers game rather than a matchup of top-20 Colorado and Oregon teams entering the last five minutes of their contest.

In what’s my personal favorite Walton moment, he jokingly gave broadcast partner Dave Pasch – who doesn’t believe in evolution – a copy of Charles Darwin’s “On the Origin of Species” as a birthday gift on air during a Colorado-Arizona game in 2015. Walton went on to confusingly ask Jay Bilas who Young Jeezy is and note that he believes in science and evolution because “I’ve been to the Grand Canyon.” As a perfect dismount to the clip, Bilas uses a reference to Pasch’s birthday cake to praise the band Cake.

For all of his quirks, what we saw during Walton’s game calls was likely an exaggerated version of himself played up for entertainment purposes. At its core, though, was Walton himself, a man who, blessed with the comfort comes with age and no longer having to worry about money in a way most other people do, didn’t have the same overbearing concerns many broadcasters do about the way they’re perceived.

There was no shortage of critiques of Walton’s on-air style, but beyond the meat of his analysis – which often contained insightful pearls for anyone willing to hear them out – his various tangents served as an omnipresent reminder that for as seriously as we all take this, what we’re watching and obsessing over is, at a fundamental level, supposed to be fun.

In the aftermath of Walton’s death, what he represented can live on

One of the more astonishing aspects of Walton’s public persona isn’t what it contains, but what it obscures. The man who is so loose, free and verbose on television has battled a stutter throughout his life.

He credited a chance encounter with hall-of-fame broadcaster Marty Glickman when he was 28 years old for helping turn his speech – and his life – around.

“The beginning of my whole new life was as simple as that,” Walton wrote in a post for the Stuttering Foundation. “No gimmicks, tricks or shortcuts. Just the realization that with some help, guidance and a lot of hard work that I too could do what seemed so easy, simple and natural to everyone else, yet seemed impossibly out of my reach and comprehension.”

It’s the sentiment that anyone like myself who stutters can relate to in some way. For me, knowing Walton’s story and seeing what he did on dozens of broadcasts throughout the season offered the kind of encouragement that wasn’t always easy to find. Not only was he speaking to an audience of millions across the country – a terrifying thought for any stutterer – but he was doing so in a way that was so unapologetically authentic to who he was.

Beyond our shared disfluency, Walton would remain a needed presence in my life.

In my time covering Pitt for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, I’d regularly find myself back at a hotel somewhere in North Carolina, Virginia or, God forbid, the frozen tundra of New York state, writing late into the night about a team that had just lost yet another game, penning stories filled with quotes from coaches and players enduring the agony that college basketball has to offer.

In the background, though, there would often be a Pac-12 game being played at some godforsaken hour, with Walton waxing poetic about something – a Grateful Dead show in Albany in 1991, the arts scene in Boulder, Colo., or some mushrooms he had found growing on a tree stump outside Oregon’s arena – that would bring a smile to my face and remind me why I loved this sport so much.

As several people noted Monday, there’s a cruel coincidence with the timing of Walton’s passing, which came only about 36 hours after Arizona beat USC in the Pac-12 baseball championship, the final game to ever take place in Walton’s beloved Conference of Champions.

Callous as some may see comparing the death of an actual human being – let alone one as beloved as Walton – with the disintegration of a sports league, it offers a potentially valuable lesson. While what transpired on Pac-12 courts that Walton oversaw for years will exist only as memories moving forward, what Walton embodied as a person can endure.

I sadly never got the opportunity to meet Walton, but everyone I knew in sports media who ever had an interaction with him spoke glowingly of him, a rare feat in what can be an industry overrun by resentment and jealousy. He wasn’t just friendly and fundamentally kind – someone who always had time for others, no matter who they were – but he was genuine. The man you saw on TV was basically who you came across in person.

He helped define college basketball as a player and worked to do the same long after his final game in 1974, using his ESPN microphone to present games as an entertaining, occasionally absurd endeavor that doesn’t have to be perpetually treated as a matter of the utmost importance – and managed to do so without being disrespectful to the coaches and players he was covering.

It’s one of the cold ironies of Walton’s death. He made the world, or at least his corner of it, a lighter place, but as Abdul-Jabbar noted Monday, it feels so much heavier without him on it.

(Photos: Getty Images, UCLA, Associated Press)